Swatting started in the gaming world and it’s coming for the rest of us

Remember ding-dong ditch?

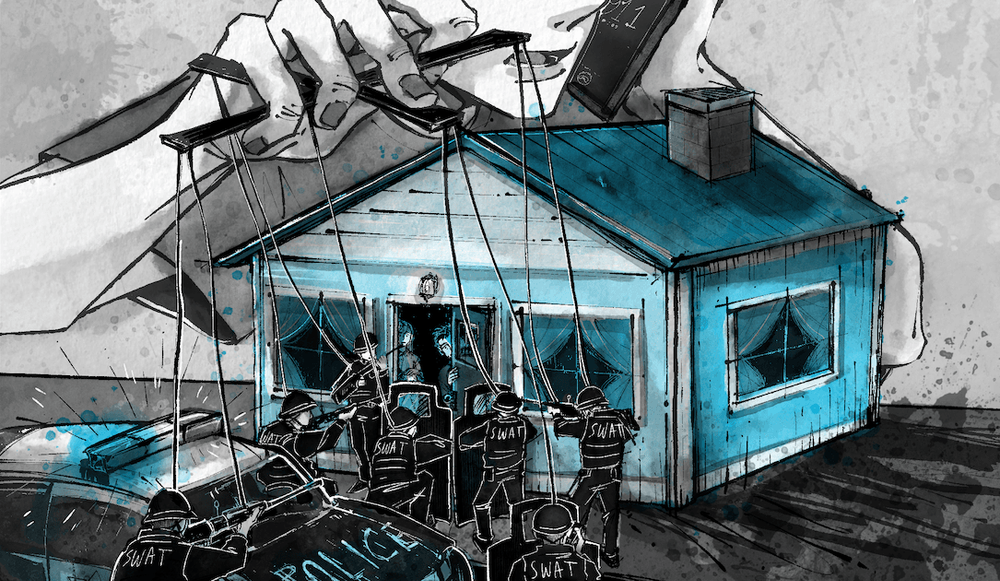

Kids would ring a doorbell — maybe numerous times in a single afternoon — and then run away. That childish prank has given way to something called swatting. Someone calls the police with a hoax report of some violent crime underway, and officers respond, appearing on the doorstep of some unsuspecting victim with guns drawn.

Swatting isn’t new. It has been going on for some time, first in the gaming community and then later among SIM card swappers and other members of the cybercriminal set.

After hundreds of schools across the country became swatting victims this past spring, legislators, law enforcement and tech companies said they would find new ways to address it.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer recently stood on schoolhouse steps and called for more federal resources to clamp down on the problem. Until just this past May, there was no national mechanism for reporting swatting incidents, and no centralized database that could help law enforcement step in before they happened.

The FBI has now created a national repository for local law enforcement to voluntarily report swatting incidents, but Lauren Krapf, director of policy and impact at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center for Technology and Society says it is just a first step.

In an interview with the Click Here podcast, Krapf explains that swatting requires a multi-pronged solution.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CLICK HERE: Hacking got its start among gamers trying to knock rivals off video games, then they targeted companies, and now it’s what we have today. If feels like swatting went through a similar life cycle, is that the right way to think about it?

LAUREN KRAPF: I think you're right about that. It really started in the online gamer and hacker communities. Oftentimes, individuals would be live-streaming themselves playing games, and their opponents would want to see some sort of SWAT engagement. There would be a police raid — even coming inside [and] knocking down doors. It really started in that way, as some sort of joke and then gained seriousness. We've known about instances of swatting since the early 2000s. But it's gotten easier and more frictionless as time has gone on. And it's gotten more popular. More coverage begets more individuals who engage in this form of digital abuse.

CH: When you talk about how it's growing more popular, do you have metrics for that?

LK: Well, it's really hard to get metrics because there is almost no real centralized reporting system when it comes to swatting. We don't have metrics, but we saw hundreds of cases last fall. It really does tend to rise and fall.

CH: I'd always heard that swatting was sort of a young man's game, as in under 18 years old. Is that still the case?

LK: It's really hard to track. Anecdotally, it is something we found that individuals who have been convicted have been younger and male. But we are finding [that] it's not majority teenagers. This really is adults engaging in this act. And that's one of the issues we've found with this gap in loopholes in the law currently across the states and at the federal level. Oftentimes, legal protections for swatting are the same as a hoax or prank call to 911. But it’s a completely different act. There's a different level of intent, and obviously the response is incredibly different.

CH: How do you fight the motivation side of this? If they were terrorists, you would understand the motivation is feeling left out. You don't have a future, and someone preys upon young men. But this is just like “ding-dong ditch” on steroids.

LK: I agree. The original gamers and hackers thought it was funny. But nowadays it's resulted in death; it’s resulted in bodily injury. Some folks think it's funny, but some individuals who are engaging in swatting are targeting people because of their race or because of their sexuality or their religion. And in that way, I have to guess that they don't think it's funny and that they really are trying to scare their target. To put a couple of numbers behind that, ADL this summer released our annual online hate and harassment survey, and it looks at the American experience of online harassment. We saw individuals who have ever experienced swatting increased. Five percent of American adults have said that they've experienced swatting in their lifetime, 2 percent in the last 12 months — and with kids, it's even more.

CH: You work for the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a civil rights group. How is it that you became an expert in swatting?

LK: I became an expert in swatting because when I joined the ADL, we decided to put more time, resources and effort into focusing on individuals being targeted and attacked online based on their race, ethnicity, gender or religion. So it immediately became an ADL issue. And as we were engaging in determining what were the biggest threats at play, swatting was coming up again and again as a form of digital abuse. There were gaps and loopholes in the law, and so we saw an opportunity to try to fill in those gaps and create better protections for victims and targets.

CH: So how do we get at this legally? When we covered violence-as-a-service, federal law enforcement was using statutes like computer abuse, or stalking or extortion to prosecute. Is that the way you get at this?

LK: It seems to be a patchwork of statutes to be able to get at this. Oftentimes, a swatter will use a bomb threat as the draw for the emergency response team. But because it's a patchwork, if there's not a fatality, it becomes much harder to hold an individual accountable. It really is a patchwork of statutes that are used at present, but that does leave a lot of room for gaps.

CH: Is Europe doing anything with this swatting problem? They seem to have beaten us to the privacy problem with GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation]. Have they addressed swatting in any significant way?

LK: I think the best model legislation is what's been passed in many states. So there is strong antis-swatting legislation in Washington, Texas, Maryland and other states across the country. And I think that what that considers is things like the actual emergency that's being communicated to 911. And it also considers that the swatter has a reckless disregard for what might happen or what might occur on the other side. So I do think that there's strong legislation in the U.S. There just need to be federal protections at play.

CH: Do you have legislators who have signed on and said, Yeah, we believe this is a problem? Sen. Chuck Schumer vaguely had this on his radar screen.

LK: We do know it's on the radar of federal legislators and we're really heartened to know that this is something they find [to be] a priority and important. We've yet to see an introduction of swatting legislation at the federal level since about 2016-17. There was a bill introduced in that Congress, but since then we haven't seen one. And at the same time with this insurgence of concern around digitally enabled abuse and also knowing that AI systems can help facilitate swatting, we are seeing that concern at the federal level. But it really is a multi-effort approach. We need to track and record these incidents. We need to ensure that when they do happen, victims and targets have recourse.

CH: You set up my next question. Back in May, the FBI set up a virtual command center for this. It’s supposed to be a kind of central clearing house to track swatting episodes, even create a realtime picture of swatting incidents. Is that the right track?

LK: We do think that is important. And my understanding is that they're providing tools and resources to agencies so that they can track swatting. At the same time, it is voluntary. I really hope that it's used robustly. A federal effort to really track and figure out tactical responses to swatting is a really important next step. Deriving insights and moving forward with increased protections would be the next step. [Note: In an interview with Click Here, FBI agent Matthew Lehman said the bureau has tracked about 200 incidents since May. “By sharing the methods by which the incidents happen,” he said, “it allows for law enforcement to be aware of how it's occurred in other locations so that they can posture themselves.”]

CH: Are you guys working with police to try and help them come up with best practices?

LK: Yes, ADL partners and does work with law enforcement agencies and coalitions across the country. The hope is that there can be better increased training — whether it's different tactical responses for that initial 911 interaction [or] engaging in a different manner when a SWAT team comes to a certain location. Now, of course, something that is a challenge for law enforcement agencies is they need to respond to emergency situations. Because if it's not a [swatting incident], and it is in fact an authentic incident, there are lives at stake.

CH: Do you have a few specific things that could help?

LK: Well, I certainly think that we need state and federal legislation that really updates those gaps and loopholes when a given statute looks at swatting the same as a prank call to 911. We need those protections, not only for victims and targets, but we also need them so that there's a shared understanding: What is the definition of swatting? When does it take place?

I also think that there needs to be better reporting and tracking across the country. We're glad to see that the FBI is looking to provide these resources for agencies. And I would say the third thing is some sort of community engagement — a way that law enforcement agencies and folks that have been targeted or might be targeted by swatting can come together and create some sort of response that is as painless and harmless to the victims and targets as possible, while still allowing for law enforcement to do their job and to respond to calls that are emergencies.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”

Will Jarvis

is a podcast producer for the Click Here podcast. Before joining Recorded Future News, he produced podcasts and worked on national news magazines at National Public Radio, including Weekend Edition, All Things Considered, The National Conversation and Pop Culture Happy Hour. His work has also been published in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Ad Age and ESPN.