Ransomware attacks hit record level in UK, according to neglected official data

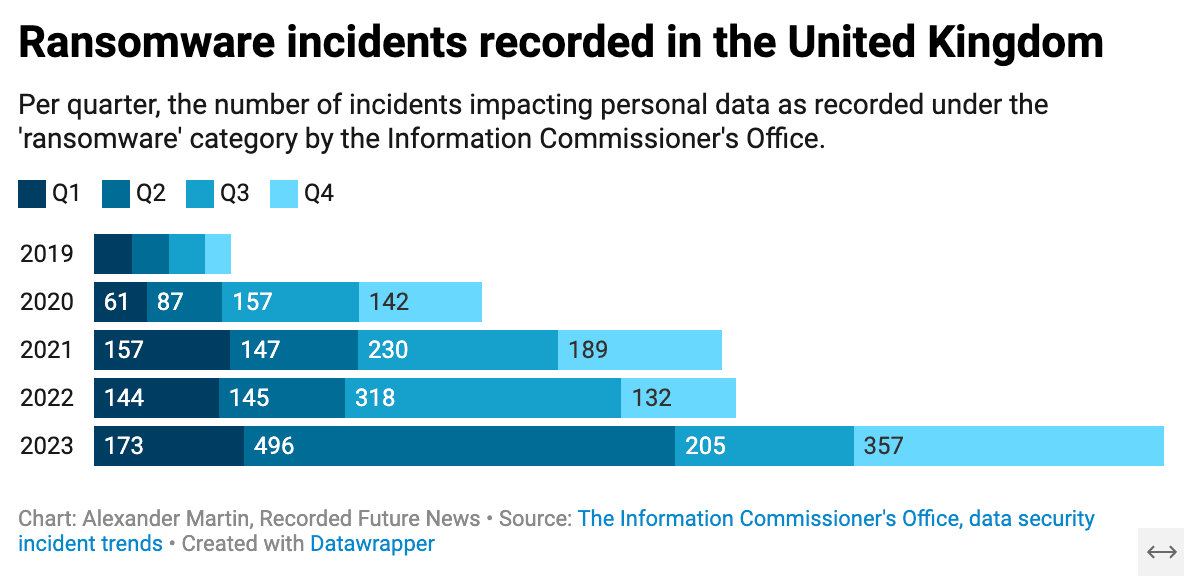

Reported ransomware attacks on organizations in the United Kingdom reached record levels last year, when criminals compromised data on potentially more than 5.3 million people from over 700 organizations, according to a surprisingly neglected dataset published by the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

The true count of ransomware incidents is a known unknown for officials trying to figure out how to tackle the problem. Victims are not obliged to report attacks to law enforcement, and darknet extortion sites only provide a partial count of victims who refused to pay. Despite frustrations around what the true figure is, few people seem to be aware of the ICO’s security incident trends data, which records the number of ransomware incidents reported to the data protection regulator.

Recorded Future News was unable to find any instances of this data being publicly cited by officials in British government departments. Jamie MacColl, a research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), said he was “surprised that this dataset exists publicly and that it’s not more widely used in cyber policy discussions about ransomware attacks in the UK, particularly given it’s been available for two years.”

A better-known attempt to establish a figure for the number of ransomware incidents in the U.K. is conducted by the government’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT), which has been compiling an annual cyber breaches survey for several years. But officials outside of DSIT say the survey is not considered particularly useful by policymakers.

They complained the survey is completely self-reported, meaning its data is biased against hacked organizations that don’t want to openly admit to an incident. The statistics it features are also produced from questions asked a year prior, meaning by the time it has been published the ecosystem is likely to have substantially changed.

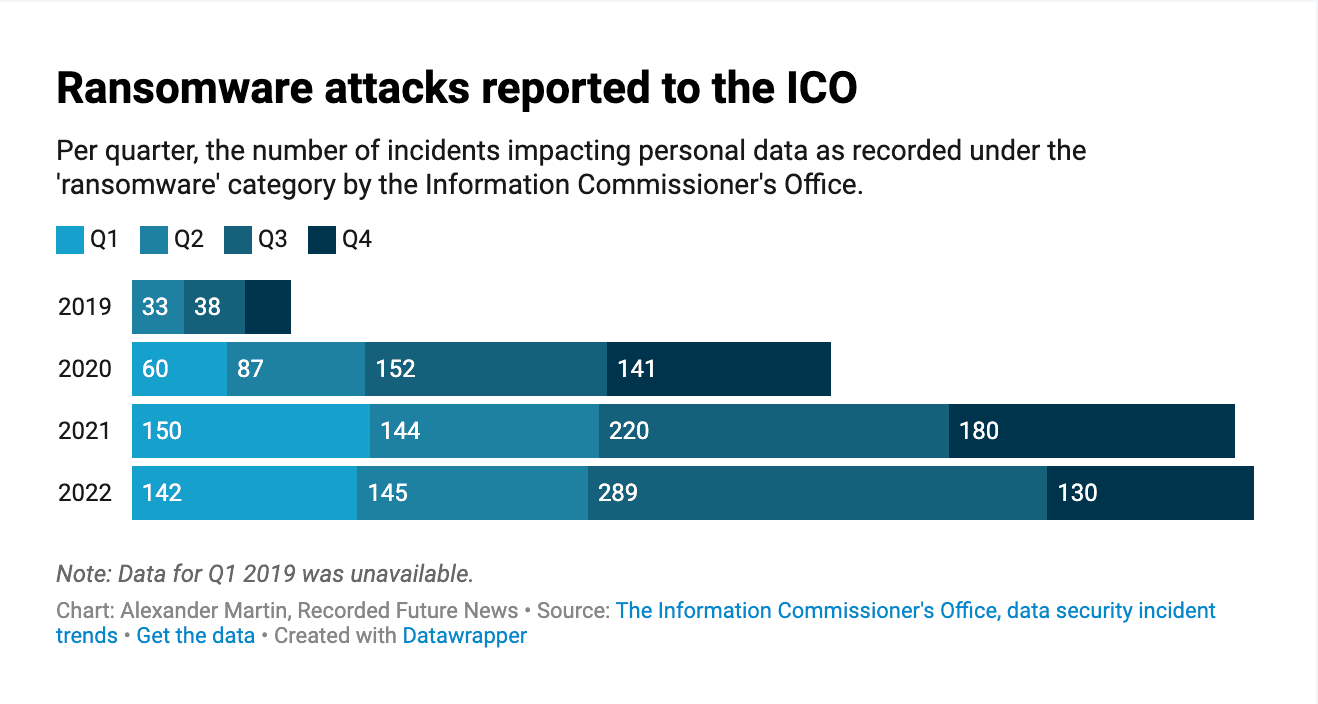

These criticisms are supported by the differences between the ICO’s data and DSIT’s self-reported survey. Where DSIT stated there had been a fall in ransomware attacks from 17% of all incidents in 2020 to just 4% in 2021, the ICO’s data instead found ransomware incidents accounted for 20% of all incidents in 2020 before rising to 28% the next year. They then continued to increase to 34% in 2022.

Unlike the voluntary DSIT survey, Britain’s data protection laws require companies to report data breaches to the ICO under the threat of being fined up to 4% of the organization’s global turnover if they fail to make a report — although no company has ever received such a fine.

Even this regulatory regime has its limitations. Earlier this year, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and the ICO published a joint blog post saying they were “increasingly concerned” that ransomware victims were keeping incidents hidden from both law enforcement and from regulators.

“As with all statistics, you need to see the ICO data through the lens in which it has been collected,” explained Hans Allnutt, a partner at DAC Beachcroft who leads the law firm’s cyber risk practice.

“The specific definition of what needs to be reported to the ICO is a personal data breach, defined as ‘unauthorized disclosure, loss, or access to personal data.’ It’s not absolutely clear whether an encryption-only ransomware attack causes a risk to personal data, because you can encrypt at a server level and not have access to personal data.”

In other words, not every single ransomware incident would necessarily need to be reported to the regulator. The ICO’s data also does not include incidents that should have been reported but were not. Despite this, Allnutt said, the data “is — in the absence of any other ransomware frequency metric or any other source of reporting — a good resource."

Acknowledging the same limitations, MacColl said it was “likely the most comprehensive public dataset about the frequency of ransomware attacks in the UK.”

The ICO has not yet published data showing the scale of the increase in 2023, but it reveals that 706 ransomware incidents were reported in 2022. Despite some speculation that the Russian invasion of Ukraine that February had slowed the ransomware ecosystem, the official figures reveal a marginal increase on the 694 reported in 2021, a significant rise on the 440 in 2020, and a huge spike from the 100 that were reported in 2019.

In a statement on Monday, the U.K.’s security minister Tom Tugendhat said: “The UK is a top target for cybercriminals. Their attempts to shut down hospitals, schools and businesses have played havoc with people’s lives and cost the taxpayer millions. Sadly, we’ve seen an increase in attacks.”

Alongside the statement, the NCSC and the National Crime Agency (NCA) published a white paper explaining the entire ransomware system. But instead of citing the ICO data on ransomware attacks, the agencies provided a global count of the number of victims listed on the ransomware gangs’ extortion sites as collected by a cybersecurity company.

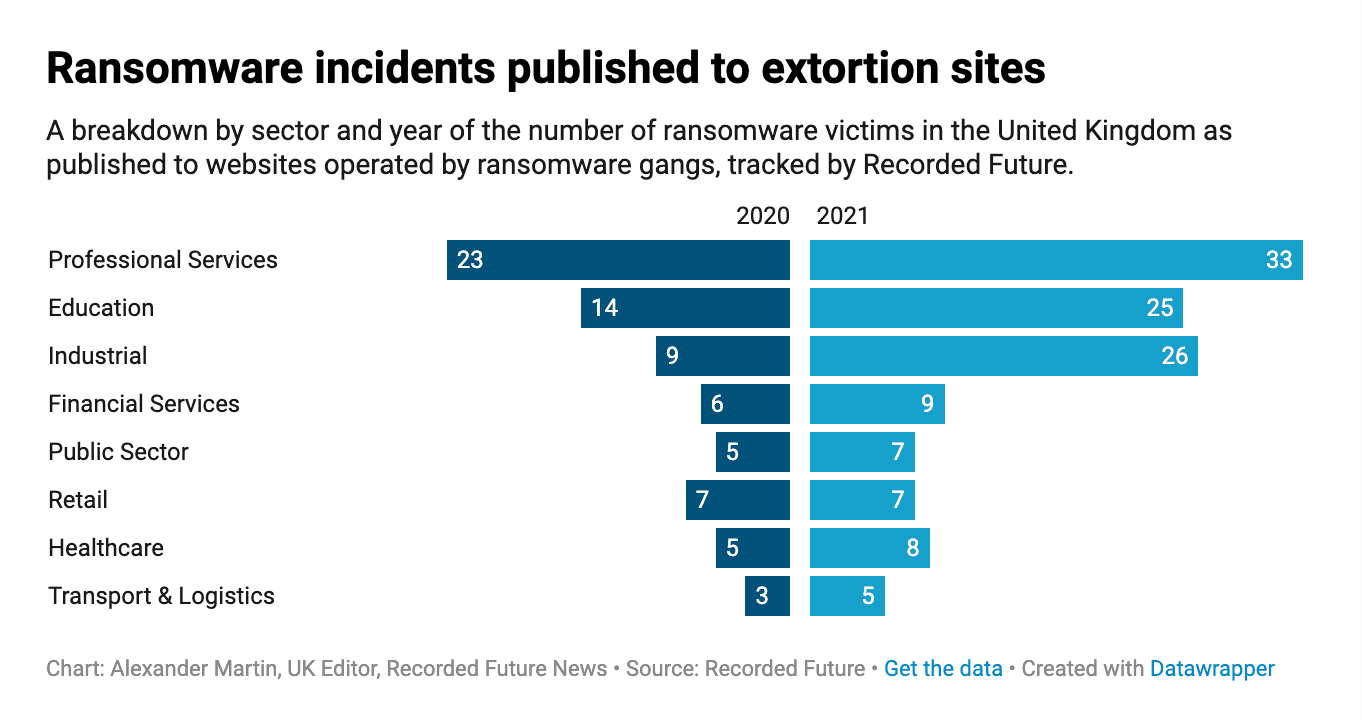

A large number of private sector organizations monitor these sites, including Recorded Future, which provided data on the number of U.K.-specific victims to The Record for a previous story.

The data shows these leak sites listed 87 attacks against British organizations in 2020; 156 in 2021; and 119 between January and September 2022 — dramatically lower counts than the numbers reported to the ICO. Again, these figures also contradict the DSIT survey’s finding that there was a substantial drop in ransomware attacks in 2021.

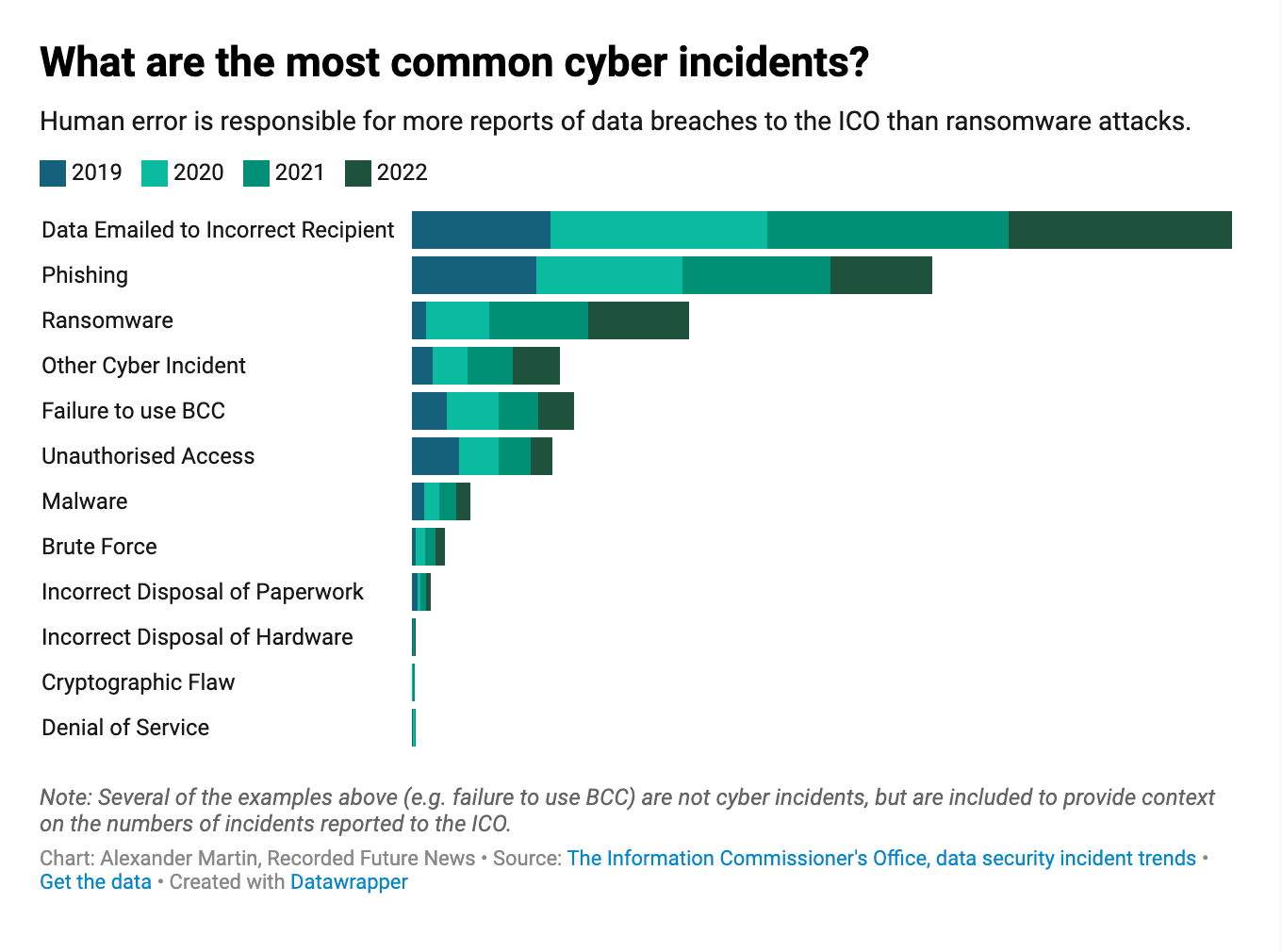

Of the ICO data in general, Allnutt explained to Recorded Future News that “some of the statistics are a little bit skewed on wider cyber incident reporting,” noting that phishing was “always quite a high category within the ICO's statistics, and it's an odd one because why would you report the receipt of a phishing email as a risk to personal data?

“People receive phishing emails all the time.”

Allnutt suggested that the phishing category included incidents “where someone has disclosed their credentials following receipt of a phishing email, and then there's access to the email mailbox,” as well as business email compromise events. “These incidents are very frequent in my experience but low impact and possibly over-reported to the ICO,” he added.

In terms of single incident types, none of the 8,265 cyber incidents — of all types, whether phishing, ransomware or malware — were individually as common as data breaches caused when staff at organizations emailed data to the incorrect recipient. These accounted for more than 5,700 reports sent to the ICO, while there were more than 1,000 incidents in which someone had failed to use blind carbon copy (BCC) when sending an email.

A spokesperson for the ICO acknowledged that differentiating different attack types was challenging because there was a degree of overlap between phishing, malware and ransomware, although the regulator provides a glossary of terms defining each.

The regulator’s data also catalogs a number of curious data breaches, including some caused by cryptographic flaws and by denial-of-service attacks. It is possible that the incidents involving cryptographic flaws could be breaches under Article 32 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which requires organizations to use an “appropriate” level of security, however it is not clear how a denial-of-service attack could put personal data at risk.

“My concern is — and it feels a bit defeatist — but when [are these attacks] ever going to stop and when is it going to go away?” asked DAC Beachcroft’s Allnutt. “We're a little bit devoid of answers because those behind ransomware are operating in that uncontrollable space, outside of favourable jurisdictions and beyond criminal and civil action.”

The cybercriminal system is “ripping money out of the country: not just the ransom payments in the rare occasions that they are paid but the damages caused from operational disruption,” he added. “And what is often not seen is the toll on those who have to respond to incidents within organisations — because behind cyber attacks are human beings who simply turn up at their job one day and suddenly have to face the weeks, months, and in some circumstances, years, that responding to a ransomware attack will take from them. It’s an awful blight.”

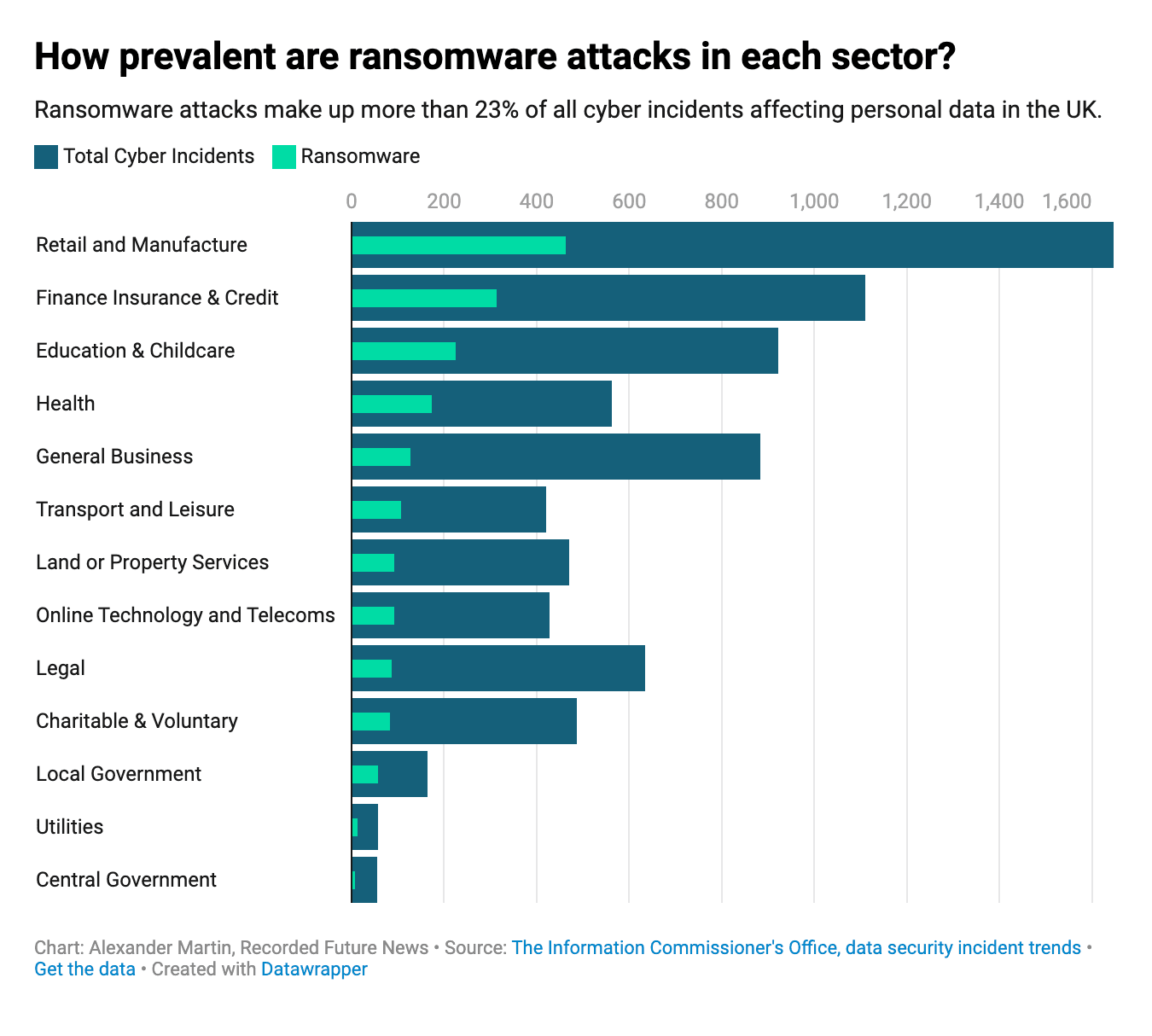

The majority of cyber incidents and ransomware attacks in the U.K. in the period covered by the data affected organizations in the retail and manufacturing sectors, closely followed by the financial sector, education and childcare, and health. While the ICO currently includes a “General Business” category, the regulator says it is phasing out the use of this term in favor of using more specific sectors.

Some sectors appear to account for a greater proportion of attacks than others. Ransomware attacks made up more than 30% of all cyber incidents affecting the health sector, with 173 ransomware attacks out of 562 total incidents. Just over 28% of all cyber incidents affecting personal data in the finance, insurance and credit sector were caused by ransomware attacks.

The ICO’s data also records 225 ransomware incidents affecting education and childcare since the reporting period began — more than 22% of all of the cyber incidents affecting the sector.

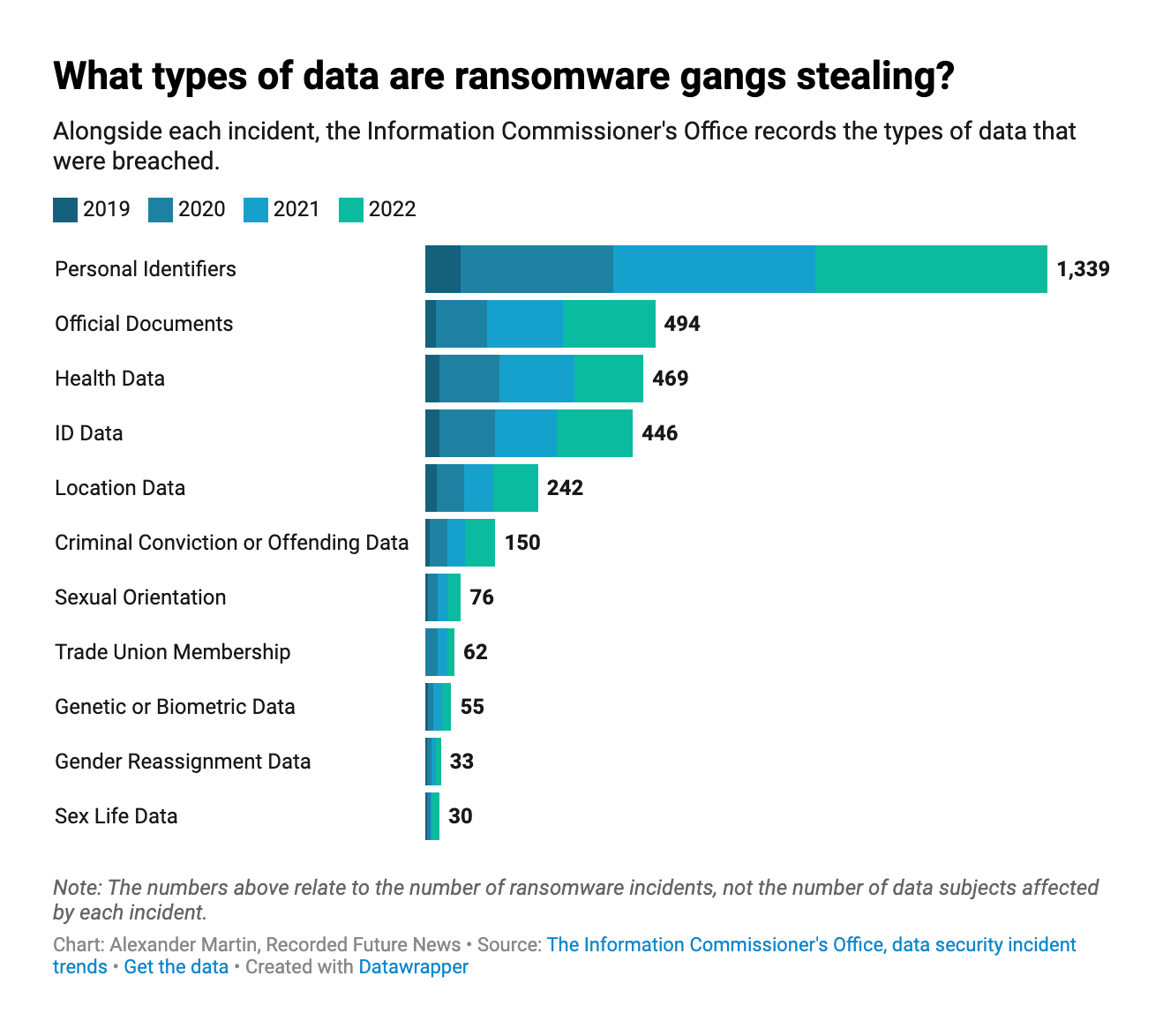

Although it is not clear how many hours of learning were lost to the attacks on the education sector, they resulted in data on at least 143,531 children being compromised — including two incidents in which “sex life data” was stolen by the cybercriminals, and 18 incidents involving data regarding children’s sexual orientation.

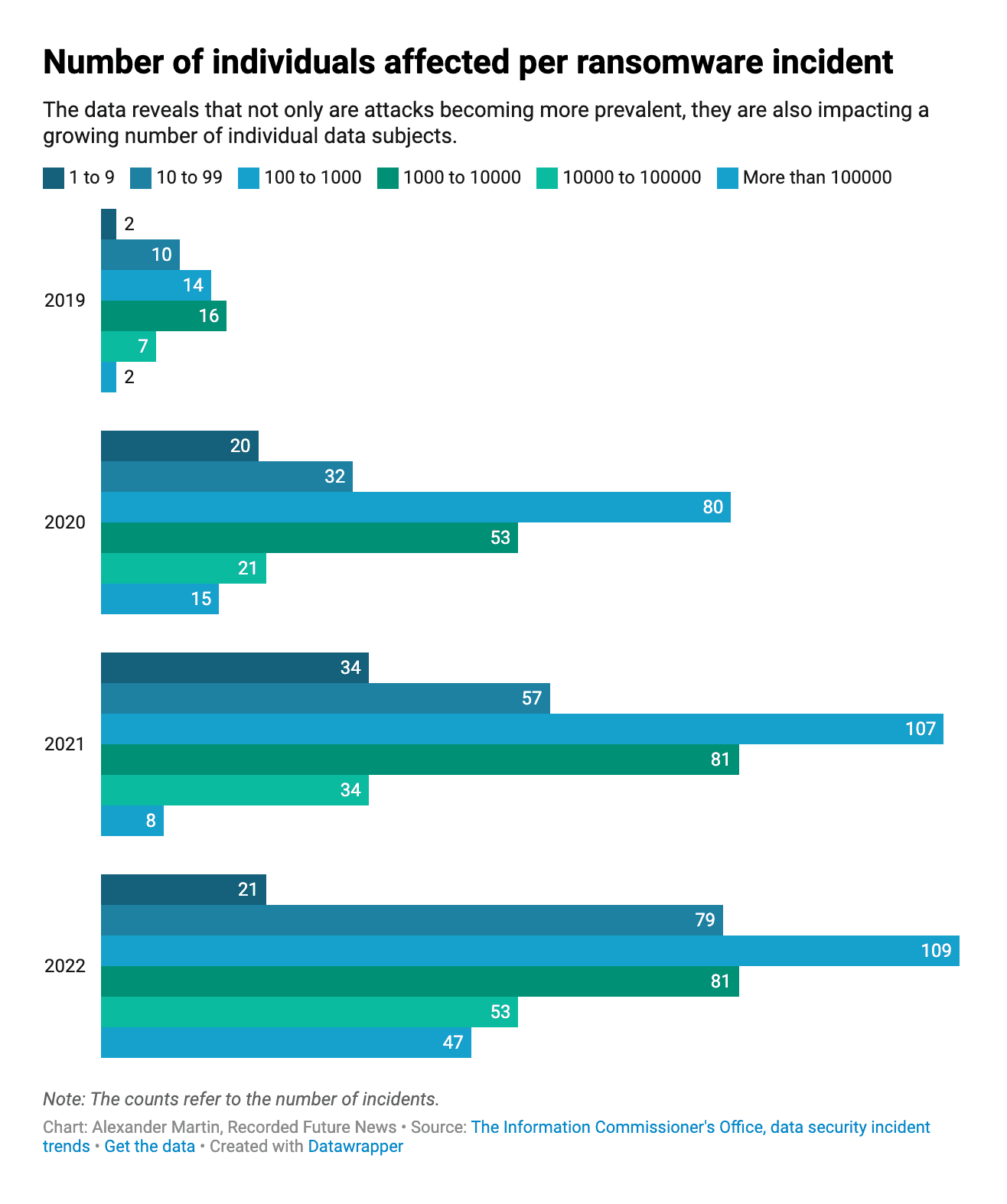

As the number of ransomware attacks has increased, so too have the numbers of “data subjects” — the individuals the data is actually referring to — whose personal information has been compromised in these attacks.

Exact figures are not included in the ICO dataset. Instead each incident gives the number of data subjects affected as a range between different powers of 10 (1-9, 10-99, 100-999, etc.). This makes an accurate count impossible. Each year contains multiple incidents where it is stated that more than 100,000 people were affected without offering an upper bound.

But by counting the number of affected data subjects using the very lowest number within the respective ranges — something that almost certainly results in a dramatic undercount — the ICO figures reveal at least 8.6 million data subjects have had their personal information compromised as a result of a ransomware attack.

This is equivalent to 12% of the United Kingdom’s entire population, although it is probable that some of the individuals affected are not located in the U.K., and that many have been affected by more than one incident.

By measuring the number of incidents reported in each year by the very lowest possible count (287,502 in 2019, 1,771,340 in 2020, 1,232,304 in 2021, and 5,322,711 in 2022) it appears that more than 60% of all personal data breaches since the records began occurred as a result of a ransomware attack last year.

Official documents have been stolen in two ransomware attacks on central government, although there is no additional data suggesting that these incidents involved classified information.

Information relating to trade union membership was also compromised in 62 ransomware incidents by the attackers. This so-called “special category data” is meant to be especially protected, according to data protection laws — similar to information about race and ethnic origin, religious or philosophical beliefs, genetics, health, sex life and sexual orientation, all of which have in varying degrees been compromised in ransomware attacks on British organizations.

MacColl, whose work at RUSI includes a research project on ransomware harms and the victim experience, partially funded by the NCSC, said: “We’ve collected very little evidence that stolen or leaked personal data… is being exploited by ransomware threat actors or other cybercriminals in a systematic way. However, that’s not to say there aren’t incidents where very sensitive information on individuals has been published or sent to them to increase pressure.”

He cited the attack on Vastaamo, a Helsinki-based private psychotherapy center, where after the institution refused to meet the perpetrator’s extortion demands, individual patients were targeted and told that they needed to pay up or have documents related to their sensitive therapies exposed online. Patient records were subsequently posted.

In a more recent example, the ALPHV ransomware group attempted to extort a healthcare network in Pennsylvania by publishing photographs of breast cancer patients.

“During our research, we also heard of cases where ransomware threat actors had targeted schools and then sent stolen safeguarding data to parents to get them to increase pressure on the schools to pay,” MacColl said.

There have also been “a very small number of examples of individuals accessing leaked data for other activities,” for instance “stalkers or domestic abusers accessing data on women whose data has been included in a breach.” But these attempts to exploit stolen data beyond using its loss as leverage to extort targeted organizations are “very much the exception to the rule,” he added.

Earlier this year, a number of gangs claimed to be launching searchable databases collating all of their victims’ personal information. But the data that was being shared — although sensitive and undoubtedly distressing — was designed to get more leverage for an extortion payment rather than to allow the data subjects to be further victimized at scale.

“Crucially, we haven’t seen evidence that cybercriminals are cleaning and aggregating leaked data in a systematic way that would allow them to sell it or use it for financial fraud,” he said.

There were several potential explanations for why, he suggested, including that the return on investment of extorting individuals over their stolen records is "several dollars at most" — a pittance considering the cost in both time and operating expenses to “host, clean and aggregate the data.”

“Lawyers and forensic experts (with specialist software) often take weeks or months trying to figure out what type of data has been stolen – the same would have to be true of the criminals too. And the data they steal often isn’t as extensive or as useful as they let on when they’re trying to extort the victim. I’m not sure they even know what they have a lot of the time,” said MacColl.

“This doesn’t rule out that cybercriminals in the future will find a use for this data, but it’s not creating a lot of real harm to individuals right now,” the RUSI specialist added.

Allnutt said the key legal risks arising from the increase in this data being available online was “in the form of regulatory investigations and sanctions, as well as compensation claims.”

“With litigation, data breach related class actions have struggled to be endorsed by the UK courts for a variety of reasons but they will not go away. What is often not reported is the relatively high volume of individual claims that are made and settled out of court,” he added.

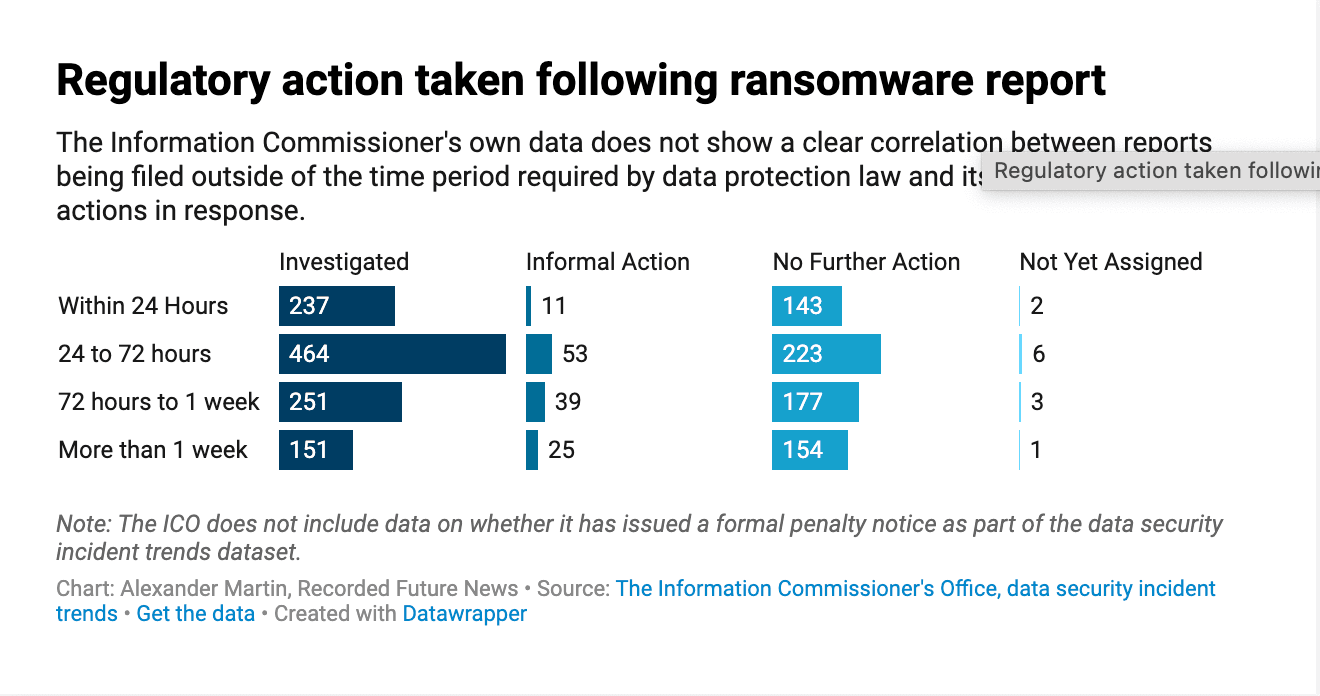

Although the dataset also records what regulatory actions the ICO took in response to these ransomware attacks, it does not show a clear correlation between whether a report was filed within the required 72 hours and the regulator taking particular enforcement actions, such as issuing a monetary penalty notice.

“The GDPR expressly states that you should report personal data breaches above a certain risk threshold within 72 hours, but if you don't, you should record your reasons for not doing so. This implies that the 72 hour deadline is not an absolute requirement,” said Allnutt.

“One of those reasons could be ‘We’re in a massive state of panic, we’re trying to switch systems off now, not fill out forms’,” he explained. “Another reason could be that you didn’t think it was a critical event as you had backups and were able to restore the system soon enough to avoid any material impact to individuals.”

MacColl, who gave a caveat that he was not an expert on data protection compliance, said RUSI’s “research on the experiences of ransomware victims in the UK has highlighted that the ICO currently has very long lead times for responding to and/or investigating ransomware attacks where data subjects are affected.”

Researchers at RUSI have spoken to a number of organizations who said “they were waiting months or even years for the ICO to conclude investigations, and that this caused considerable stress and even anxiety among staff.”

“Although some of these incidents are complex and require longer investigations, these waiting times also highlight the considerable backlog and resourcing challenges faced by the ICO. It’s fair to say that there are more important things that ICO staff could be working on than mistakes with emails,” MacColl said.

Allnutt added that the office has a range of responsibilities separate from security breaches, including handling myriad types of data subject complaints.

“So you can fall into a trap sometimes and think ‘Oh, the ICO isn’t taking regulatory action, oh it’s terrible that they aren’t holding companies to account.’ They do an awful lot and have an awful lot on their plate.

“Taking regulatory action is not just filling out a form and issuing a fine, it’s months of work for a case handler at the ICO and the caseload isn’t going away.”

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative, now Virtual Routes. He can be reached securely using Signal on: AlexanderMartin.79