Hundreds of thousands trafficked into cyber scamming in Southeast Asia, UN says

More than 200,000 people are being forced to carry out cyber scams in Southeast Asia, the United Nations estimates.

A report published Tuesday by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights documents the monumental scale of trafficking into an illicit industry that took off following the pandemic and shows no sign of slowing down.

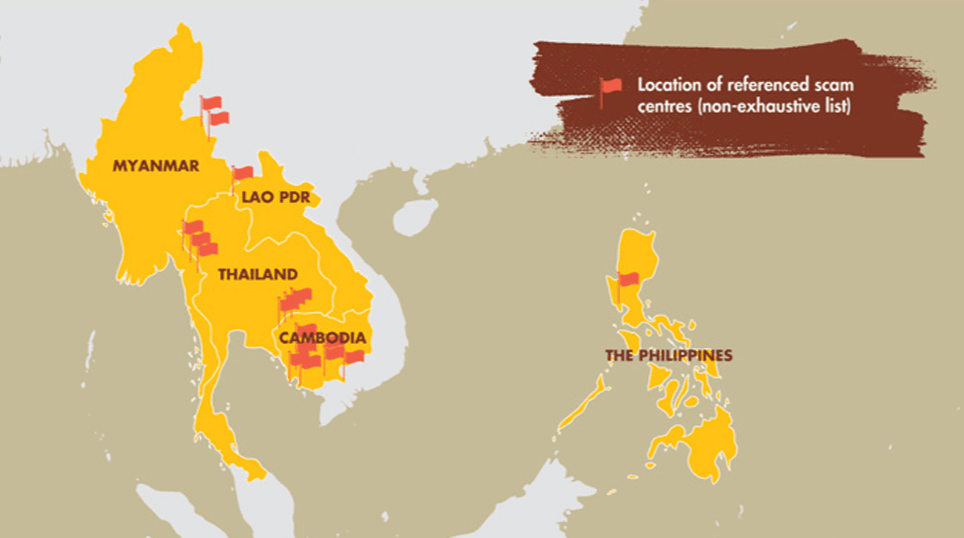

In Cambodia, at least 100,000 people are involved against their will, while in Myanmar “credible sources” estimate 120,000 are being held, OHCHR wrote. Victims have been trafficked from all over Asia, as well as East Africa, Egypt, Turkey and Brazil.

Typically, people will respond to job opportunities posted on social media promising decent pay in work related to information technology. Usually the job will involve relocating from the applicant’s home country.

Upon arrival, the reality is much different from what was advertised. Workers are often essentially imprisoned in compounds alongside other trafficked victims, their passports confiscated, and they are forced to carry out online scams — most commonly “pig butchering” schemes in which they develop a relationship with a target on messaging apps, build up their trust, and trick them into making fraudulent cryptocurrency investments.

The U.N. estimates that the Southeast Asian scams have generated billions of dollars’ worth of revenues.

Such trafficking took off amid COVID-19 lockdowns when casinos, a major income source for organized crime groups, were forced to close their doors.

“Faced with new operational realities, criminal gangs increasingly targeted migrant workers, who were stranded in these countries and were out of work due to border and business closures, to work in the scam centres,” the U.N.’s human rights office wrote. “At the same time, the pandemic response measures saw millions of people restricted to their homes and spending more time online, making them ready targets for this online fraud.”

When borders once again reopened, the gangs had a susceptible labor pool to target, and “continued to exploit the economic distress that had resulted from the pandemic and the needs of many to find alternative livelihoods.”

Organized crime groups also took advantage of political upheaval in Myanmar, with scam operations in virtually lawless areas along the border with Thailand and China increasing since a military coup in February 2021. The U.N. also cites Laos and the Philippines as hotspots for cyber-related trafficking.

Credit: U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Credit: U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

China, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar recently set up a center in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai to coordinate anti-cybercrime operations next door, and last week, the Thai, Laotian and Chinese ambassadors to Myanmar released a joint statement calling for “efforts to crack down on gambling syndicates.”

Incomplete protections

For people who do manage to escape the compounds — often through rescues carried out by anti-trafficking groups, raids, or via ransoms paid by their families — their troubles don’t end there.

Even though all countries in Southeast Asia are parties to the U.N. Trafficking in Person Protocol — a framework to define and address trafficking — local laws often fall short in protecting people shuttled into cyber scamming.

In Thailand, for example, the national police estimated that 70% of people who returned to Thailand after being trafficked into cyber scamming were prosecuted for their alleged crimes. The country’s Anti-Human Trafficking Act exempts victims from being prosecuted for certain crimes, but scamming isn’t one of them.

“With the exception of Malaysia, all Southeast Asian countries are failing to recognise forced criminality as a purpose of exploitation under the legal definition of trafficking,” the U.N. wrote. Furthermore, rescued victims are often detained in countries like Cambodia for violating immigration laws, unable to prove that they were brought to the country on false pretenses and held against their will.

The report’s authors recommend national legislation to address the unique characteristics of cyber-related trafficking, which often starts with voluntary travel across borders.

Additionally, the U.N. body called for local law enforcement to help victims, rather than prop up the illegal enterprises.

“Victims have also alleged that law enforcement officials directly assisted their traffickers, for example in facilitating travel across international borders or working as guards in the scam centres,” they wrote.

“States have an obligation to combat corruption as part of their broader human rights commitments and promotion of good governance and the rule of law.”

James Reddick

has worked as a journalist around the world, including in Lebanon and in Cambodia, where he was Deputy Managing Editor of The Phnom Penh Post. He is also a radio and podcast producer for outlets like Snap Judgment.