How Cambodia-based scammers made an estimated $3 million in ‘pig butchering’ scheme

Last October, Sean Gallagher received an unexpected text message from a young Malaysian woman calling herself Harley.

She said she ran a wine business in Vancouver that was struggling due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and as a result Harley learned how to make money through cryptocurrency trading. She was willing to share her secrets, she said. Gallagher, a senior threat researcher at cybersecurity firm Sophos, happily accepted.

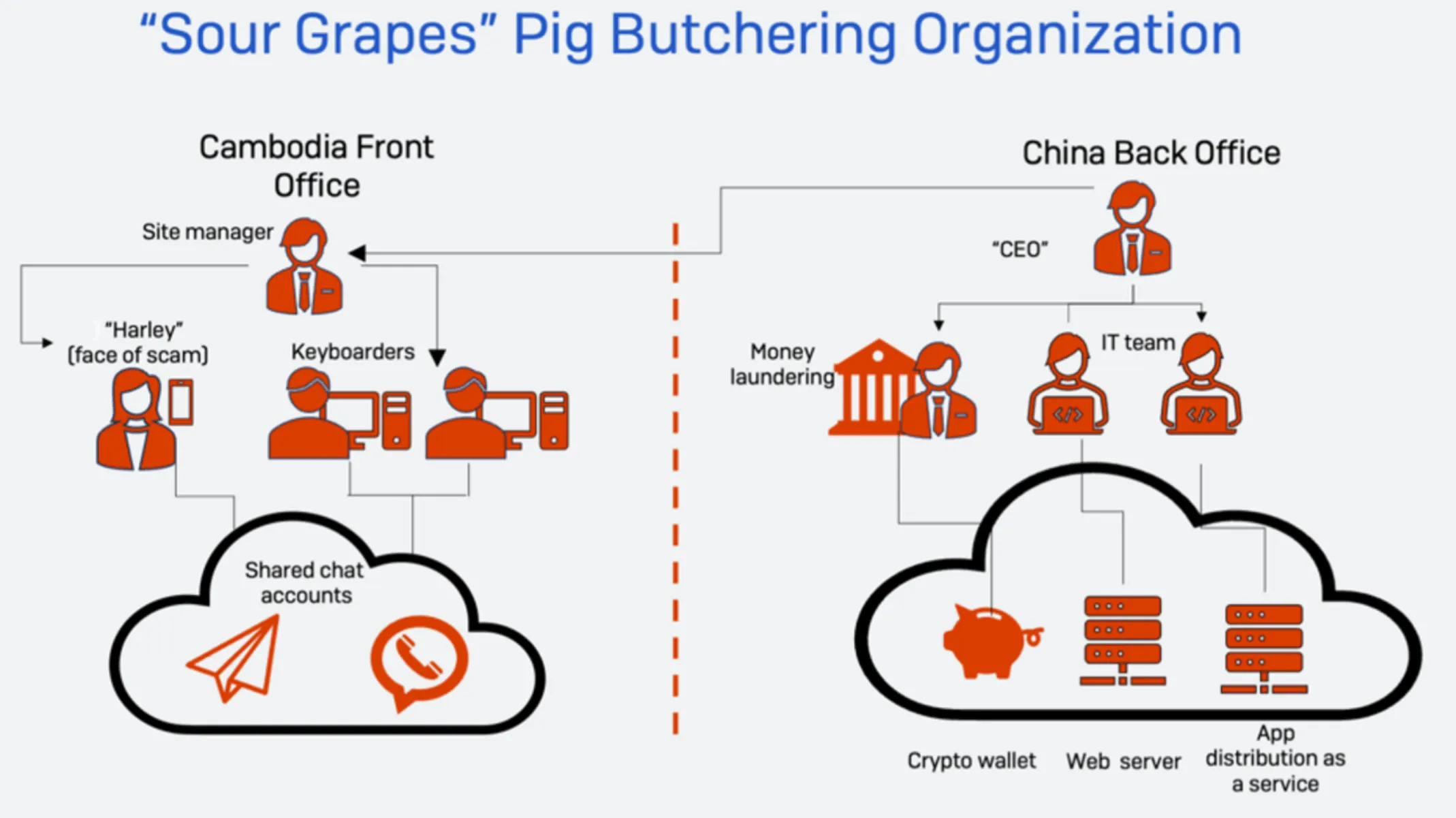

The conversation with Harley led him to discover a Cambodia-based threat actor, which he dubbed "Sour Grapes," that allegedly made over $3 million in cryptocurrency over a period of five months through a so-called pig butchering scheme.

In these scams, cybercriminals use social engineering tactics to trick victims into revealing sensitive information or transferring money. Hackers often find their victims through dating apps, social media sites, and even random SMS texts, as in Gallagher’s case.

These texts appear as accidental messages but are actually designed to spam a large number of potential victims and selectively engage with those who reply. Scammers usually convince their victims to switch to another messaging platform (in Gallagher's case, Telegram) and then trick them into depositing money into fake decentralized finance apps.

The scam ring exposed by Sophos is one of hundreds using similar lures and nearly identical websites and apps, Gallagher said. While Sophos was preparing its report, for example, it was contacted by an individual in the U.S. whose story almost exactly mirrored Gallagher’s experience with a few exceptions — the woman claimed to be Vietnamese, running a makeup business from New York.

This type of lure is particularly popular among Chinese organized crime operations working out of countries in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos, Gallagher said.

The scam teams usually have a young person as the front — people like Harley who keep the victim talking — and a group that creates fake media content to provide false proof of the scam's story.

The long duration and complexity of the communications these scam rings maintain make them convincing to even skeptical targets, according to Gallagher.

But the scam is rarely flawless: sometimes the story is inconsistent, the scammers do not speak good English, and are too open about their motives — to get their victim to invest money in cryptocurrency.

Harley, for example, instructed Gallagher to buy at least $2,000 worth of cryptocurrency with a crypto.com wallet and sent him a link to a fake app that analyzes financial market data and generates charts.

Gallagher was able to identify similar web and Android apps, all coded by Chinese-speaking programmers, he said.

“If these organizations start learning how to create more consistent, locale-specific technology footprints, then these scams could become much more convincing and catch even more victims with their lures,” Gallagher said. “Education on the scope of these scams remains the best defense against them.”

Daryna Antoniuk

is a reporter for Recorded Future News based in Ukraine. She writes about cybersecurity startups, cyberattacks in Eastern Europe and the state of the cyberwar between Ukraine and Russia. She previously was a tech reporter for Forbes Ukraine. Her work has also been published at Sifted, The Kyiv Independent and The Kyiv Post.