How Italy became an unexpected spyware hub

In April 2022, about four months after Kazakhstan’s government violently cracked down on nationwide protests, cybersecurity researchers discovered that authorities in the country were deploying spyware on smartphones to eavesdrop on citizens.

The tool wasn’t developed by Kazakhstan, nor was it purchased from Israel or other countries typically associated with spyware. Instead, researchers linked it to RCS Labs, a relatively unknown Italian firm that has been operating since 1992.

The spyware, known as Hermit, is believed to have been used in several other countries including Syria and Italy. Documents published by Wikileaks in 2015 show that RCS had engaged with military and intelligence agencies in Pakistan, Chile, Mongolia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Vietnam and Turkmenistan, according to a blog post from Lookout, the cloud security company which discovered Hermit.

RCS is just one node in a web of spyware vendors operating out of Italy with little oversight, according to cybersecurity researchers and Italian spyware experts. The country is home to six major spyware vendors and one supplier, with many smaller and harder-to-track enterprises emerging all the time, experts say.

Although much attention is given to sophisticated, zero-click spyware developed by companies like Israel’s NSO Group, the Italian spyware marketplace has been able to operate relatively under the radar by specializing in cheaper tools. According to an Italian Ministry of Justice document, as of December 2022 law enforcement in the country could rent spyware for €150 a day, regardless of which vendor they used, and without the large acquisition costs which would normally be prohibitive.

As a result, thousands of spyware operations have been carried out by Italian authorities in recent years, according to a report from Riccardo Coluccini, a respected Italian journalist who specializes in covering spyware and hacking.

“Spyware is being used more in Italy than in the rest of Europe because it's more accessible,” Fabio Pietrosanti, president of Italy’s Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights and a prominent ethical hacker there told Recorded Future News. “Like any technology or any investigative tool, if it's more accessible, then it will be more used. That's just the natural consequence.”

A history of reform efforts

In 2017, Pietrosanti worked on legislation meant to better regulate the use of spyware by Italian authorities. While the bill failed when the ruling party changed, some of the principles it introduced are included in a new spyware reform bill which will go into effect in February, he said.

The reform effort was undertaken with several Italian luminaries and spearheaded by former Italian Parliament member Stefano Quintarelli.

When Quintarelli was elected to Parliament in 2013, he was shocked to learn how spyware was being used by Italian authorities, he said in an interview.

Quintarelli still recalls the moment when he decided to draft the bill: It was a Monday, and his assistant shared a list of legislative amendments that had just passed. He immediately noticed one proposed by the Ministry of Interior that allowed the usage of spyware for “a very wide range of possible crimes and without appropriate safeguards,” he said. “I looked at that and I said, ‘Wow, there must be something that I don't understand.’”

He soon found that he understood. And he knew it had to change.

In addition to being a former member of Parliament, Quintarelli spent eight years as the president of the Italian government’s lead digital agency and also served as chairman of a United Nations advanced technologies advisory group.

The new law taking effect in February won’t solve all of Italy’s problems. It is now impossible to track exactly who is deploying spyware and how they are using it, Quintarelli said, because there is no central body in charge. The reform package doesn’t substantially improve that, he said.

However, the new law does make some fixes. Quintarelli’s failed legislation sought to limit when and how spyware could be deployed in investigations, he said, because too often it was used early on to help the authorities learn information that they would then confirm in another way. The newly passed reform bill includes a similar provision.

“During my preparative work for the bill proposal I was told they snoop into your phone and they find interesting stuff, and then they cannot use that directly so they stop you, they grab your phone, they ask you to unlock it, and then, ‘Oh, right, I see there is some incriminating evidence in the phone,’” he said.

Most fundamentally, the new reform bill requires that an investigating judge provide an “independent evaluation” of the specific reasons for why law enforcement needs to use spyware and determine whether there is cause in each specific instance.

Italy’s longstanding spyware market

A 2021 report from the Italian legislature details how authorities there allegedly misused RCS spyware. The document reveals that RCS maintained an office inside of the Naples public prosecutor’s headquarters through which it could access data sent to “all the Italian prosecutors' offices to which RCS supplied the [spyware] technology.”

The sensitive data was not encrypted and could be accessed remotely by RCS system administrators, which the report said was illegal.

“This story, in some ways Orwellian, confirms the extreme delicacy of the use of the computer interceptor, which, if not regulated in an extremely rigorous way, is exposed to abuse and to the risk of altering the authenticity of the evidence,” the legislature’s report said.

Italy’s experience highlights what critics inside and outside of Europe have portrayed as a disturbing tendency of some European governments to deploy spyware all too readily and often unconstitutionally.

Against this backdrop, Italy has become one of three top global spyware hubs alongside India and Israel, according to spyware experts behind a recent Atlantic Council report.

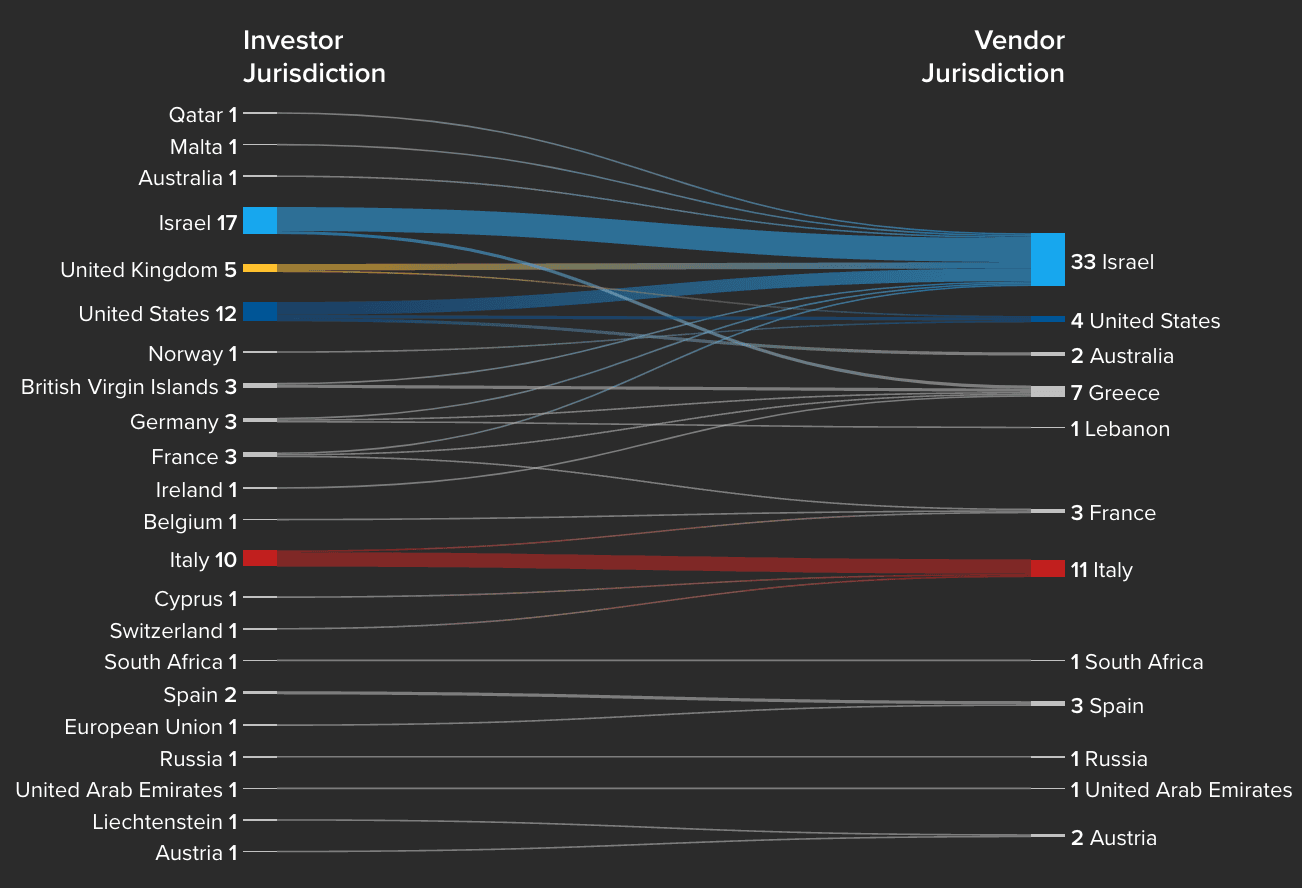

Money flows from investors to vendors. Almost 50% of investors are incorporated in Israel, the U.S., the U.K. and Italy. Image: Atlantic Council

The first Italian spyware company — RCS — entered the scene back in 1992 well before spyware marketplaces formed in other European countries, said Jen Roberts, a co-author of the report.

The Italian market also is the longest running continuous spyware ecosystem the Atlantic Council found in the 42 countries which they studied, she said.

Hacking Team — an Italian spyware company which has changed its name to Memento Labs but retains much of the same leadership and staff — is more than 20 years old and is among the country’s most prominent vendors, Roberts said.

It is not presently sanctioned and does not appear on the U.S. entities list unlike several spyware firms tied to Israel, she said, likely because European companies are not typically sanctioned by U.S. authorities and because Italian spyware has not been found to have directly impacted Americans.

Law enforcement demand

Spyware firms operating in Italy are generally small companies whose software cannot be installed without users clicking on a link, at least as far as researchers and experts know. The fact that these companies most likely can’t offer stealthy infections — like NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware — keeps pricing lower.

However, once installed, the spyware sold by these companies is as invasive as Pegasus, which can capture all emails and phone calls made on a device and even turn on its microphone and camera to capture audio and images.

Despite providing these powerful capabilities, Italian experts say, the fact that the companies selling spyware there are small-time enterprises when compared to NSO Group makes them more common and harder to police.

Law enforcement in Italy is well-positioned to take advantage of the competitive marketplace by procuring spyware for next to nothing. The low prices set by the Italian Ministry of Justice allow investigators to use the tool without large acquisition costs.

In Italy, no central national or even regional authority governs law enforcement use of spyware. It is easy for prosecutors to procure it with authorization from judges at the local level, Italian experts say, and there is no larger entity overseeing those judges.

A decade ago the country’s highest court ruled that Italian law enforcement can ”inject spyware with the very same authorization it needs to plant a microphone bug,” Pietrosanti said.

As a result prosecutors moved beyond deploying it just for major mafia and terrorism cases to also using it in drug cases and those involving other lower-level offenses, Pietrosanti said.

That ease of use, and the frequency with which it happens, is directly responsible for an Italian marketplace teeming with spyware companies, he said.

The total number operating in the country is much higher than the six flagged in the Atlantic Council report, according to Pietrosanti.

The companies providing Italian law enforcement with spyware also sell more pedestrian investigative tools, Pietrosanti said, including RCS. These larger relationships make spyware procurement more seamless and natural, he said.

“They sell you an IP interception system, a voice interception system, a GPS data log with geofencing, a translation system,” he said. “So they create an entire surveillance suite for investigations and one module is spyware — it is just another information collection module on top of other existing technology that is already being provided.”

Europe’s spyware problem

The prolific use of spyware by local Italian police forces and prosecutors is happening as human rights activists and even some European Union leaders are condemning governments there for doing nothing to stop the intensifying use of spyware on the continent. Major scandals involving infections of civil society leaders, journalists and opposition politicians have rocked Europe as Greece, Spain, Hungary and Poland all have been caught using the surveillance tool against citizens uninvolved in terrorism or crime in recent years.

Attempted spyware hacks also have hit mainstream European leaders, including the European Commission’s Justice Minister.

The president of Europe’s Parliament, Roberta Metsola, was targeted with powerful Predator spyware last year. She is one of several Parliamentarians or staff members to have been targeted with surveillance technology. Many of the infected devices have been discovered with traces of spyware during routine security checks undertaken because of spyware’s prevalence on the continent.

“They know what they have to do,” said Sophie in ’t Veld, a European Parliament member who led a Parliament investigation into spyware abuses, referring to national governments. “The problem is they don't want to do it.”

“They kind of like their little toy and they're very reluctant to give it up,” she added, speaking as part of a panel discussion in May.

As Italian spyware companies have multiplied with the support of police and prosecutors there, exports of the technology have increased. Lax licensing requirements and poor enforcement of export controls have enabled foreign sales, and profits, for Italian companies, Italian experts said.

A lack of regulation for spyware exports is a problem across Europe and in Italy this reality has bolstered the vendors who operate with impunity inside the country. The diffuse domestic user base has bred more suppliers, experts say, and those suppliers have had to expand their overseas customer base to thrive in a competitive Italian market.

After the Italian Ministry of Justice set pricing limits a couple of years ago, profits shrunk and many companies beefed up their export business, Pietrosanti said. The government did very little to regulate who they sold to, he said.

“Italy's public spending has created a domestic market of companies that sell and produce spyware, both domestically and abroad,” said Coluccini, who reports for Italy’s IrpiMedia.

An unclear future

That may or may not soon change.

The new law should force law enforcement to stop depending on spyware so regularly, Pietrosanti said.

“We are heading to normalization, hopefully,” he said, but added that there are still many questions about how effective the reforms will be once implemented.

The new law won’t change the fact that police and prosecutors can procure spyware locally so it will still be easily accessible, Pietrosanti said.

For his part, Quintarelli thinks the new law will strengthen the Italian spyware ecosystem. While there is ample room for improvement in the reform package he said regulation in any form will give the ecosystem more legitimacy and lead to a stronger spyware business environment in the country.

Italy’s long-standing marketplace and the talent within it have only attracted more talent, he said, and that talent isn’t going anywhere.

By forcing companies to play by the rules, the government is ensuring that spyware vendors will ultimately be more sought out, he said.

“Putting in strong safeguards does not diminish the value of the market,” Quintarelli said. “It augments the value of the market.”

Additional reporting by Alexander Martin

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering digital privacy, surveillance technologies and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.