UN Security Council members meet on spyware for first time

Members of the U.N. Security Council for the first time gathered Tuesday to discuss the threat posed by commercial spyware at an informal meeting where a senior U.S. diplomat called for enhanced efforts to obtain justice for victims of the technology, and other nations pledged to take action.

The meeting — known as an Arria-formula, to discuss pressing problems outside the full council — comes at a time when increasing attention is being paid to how spyware is infecting devices belonging to diplomats.

The U.S. National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal 2025 includes a measure meant to better protect diplomats from commercial surveillance technology by requiring the State Department to adopt stronger cybersecurity standards, alert Congress to spyware incidents and study past targeting by the software.

The U.N. session included an announcement from Slovenia that it will become the 23rd country to sign the U.S.-led joint statement designed to promote measures to counter spyware abuses.

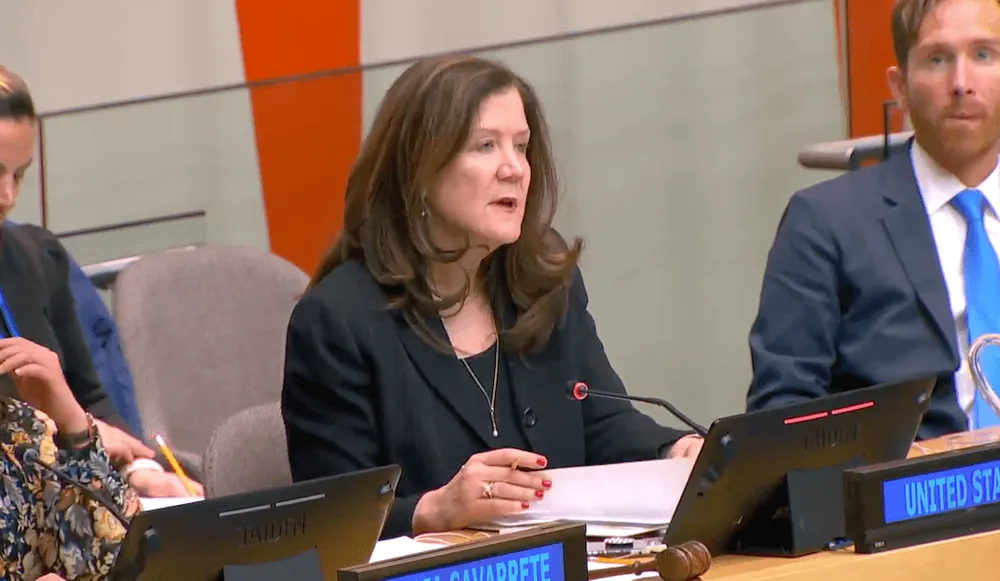

Amb. Dorothy Camille Shea, the deputy U.S. representative to the U.N., called on governments to “strengthen export controls, to curb the proliferation of these technologies without guardrails, and to provide remedy and justice for victims of commercial spyware.”

“These measures are the only reasonable response to a threat that undermines our nations’ sovereignty,” she added.

Shane Huntley, senior director of Google’s Threat Analysis Group, told the gathered diplomats that his outfit is now actively tracking about 40 commercial surveillance vendors.

Well-known companies peddling spyware such as the NSO Group get all the headlines, Huntley said, but dozens of smaller vendors are contributing to the problem.

“While these vendors claim to vet their customers and usage carefully with the promise that their work is only used to target criminals and terrorists, what we have observed time and time again is … that these tools are used by governments for purposes at odds with democratic values,” Huntley said.

Twenty of the 25 zero-day exploits — infections that leverage previously unreported software bugs — that TAG discovered in 2023 were being used by spyware companies, Huntley said.

Europe has been at the center of spyware scandals in recent years as revelations of abuses have been exposed in Greece, Hungary, Spain and Poland.

“Civil society has watched in puzzled wonderment as Europe sleepwalks into a mercenary spyware crisis,” John Scott-Railton, a researcher from the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, said at the U.N. event. “Europe is an epicenter of spyware abuses and increasingly playing host to spyware companies.”

A representative from Italy said at the meeting that national legislation to combat the problem must advance at home. Poland’s diplomat said legislation is already underway there.

Still, most countries in Europe have not yet adequately addressed the problem, according to human rights activists and digital forensic researchers.

Scott-Railton pointed to the fact that U.S. authorities have said at least 50 officials have been targeted with the technology and that spyware infections have been found on networks belonging to the prime minister’s office in the United Kingdom as well as the U.K. Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office.

Scott-Railton urged the Security Council to merge its increasing focus on cyberthreats with an enhanced program to combat spyware.

The diplomat representing the U.K., Archie Young, said that the burgeoning spyware market has drastically changed the cyberthreat landscape. The U.K. is committed to taking domestic measures to tackle the problem, he said.

“This is a threat to us all,” he said.

China and Russia objected to the U.S.-led hearing. China said the priority should be stopping nation-state cyberweapons like the Stuxnet virus used against Iran’s nuclear weapons program. Russia said the broader U.N. community should convene on spyware. Edward Snowden’s leak of information about National Security Agency activities showed the U.S. to be hypocritical on surveillance technology, Russia said.

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering digital privacy, surveillance technologies and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.