The Company Man: Binance exec detained in Nigeria breaks his silence

The rest of the world found out just how bad things had become for Tigran Gambaryan when a haunting video began to make the rounds. Just 39 seconds long, it was shot selfie-style and showed Gambaryan — bearded with a tight haircut — looking down into the phone as if he was hiding it.

“I don’t know what is going to happen to me after today,” Gambaryan began in the video that surfaced last March. “I have done nothing wrong. I’ve been a cop my whole life. I’m asking the United States government to assist me… I need your help guys, I don’t know if I’ll get out of this without your help. Please help.”

Gambaryan was finally released on a medical parole late last year and recently sat down with the Click Here podcast for his first audio interview since all this began. The story that emerged isn’t just about one man held captive in a notorious Nigerian prison. Instead it is about how people, living in places without stable economies, have found a kind of refuge in cryptocurrency and how local officials are doing all they can to try to stop it.

Gambaryan in his home outside Atlanta in December 2024, shortly after his release. Image: Sean Powers/Recorded Future News

Gambaryan made his name working for the Internal Revenue Service. He was a special agent there for more than a decade and turned tracking cryptocurrency crimes into a kind of specialty. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say he helped pioneer the field of cryptocurrency investigations — he had a hand in rolling up some of the biggest names on the dark web, including the alleged founder of AlphaBay, Alexandre Cazes, and Silk Road’s Ross Ulbricht, who went by “Dread Pirate Roberts" and was recently pardoned by President Donald Trump.

In many ways, Gambaryan became something of an evangelist for cryptocurrency. He believed that, if done correctly, crypto could solve a lot of the problems in the traditional banking system and provide a new kind of transparency for law enforcement officials around the world like him. When he joined the cryptocurrency exchange Binance in 2021, he did it with an eye toward teaching a whole generation of cops around the world how to track cryptocurrency just like he did.

Economic Woes

To understand how Gambaryan ended up in detention for eight months, it’s important to understand Nigeria’s complicated relationship with cryptocurrency. By the time Gambaryan had arrived to talk with regulators from Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), the nation was in the midst of a full-blown economic crisis.

Inflation was running well over 30 percent. The government unpegged the naira from the U.S. dollar and watched it lose some 40 percent of its value. Just to keep up with inflation, Nigerians started flocking to cryptocurrencies and trading stablecoins — which are pegged to the U.S. dollar — amongst themselves, peer-to-peer.

Binance helped facilitate those trades. And while it didn’t control them or set a target rate for the value of the naira, the sheer fact that ordinary Nigerians could vote with their feet and pile into cryptocurrencies angered regulators there, according to financial observers. The central bank’s hold on the value of the country’s currency felt like it was slipping away.

According to Feyi Fawehimni, a Nigerian scholar who has been writing about the nation’s economic and political affairs for more than a decade, it was easy to blame Binance for everything that was going wrong with the Nigerian economy.

“People who wanted simple answers simply turned and said, ‘Oh, OK, this economy is struggling. Nobody has dollars, whose fault is this?'” he said. “The central bank thought it had lost control, so Binance became a kind of scapegoat.”

And by extension so did Gambaryan.

Fateful Meeting

Gambaryan’s trip to Nigeria last February was scheduled as a few days of back-to-back meetings before he would fly home to the U.S. He didn’t even check a bag.

Gambaryan was under the impression that he and a colleague would be meeting with, among others, a man named Nuhu Ribadu, a key Nigerian official who served as the national security advisor to the president. He had helped stand up the EFCC, one of Nigeria’s top anti-graft agencies. “They were like, oh, just come in, just sit down, they’ll come in a little bit,” Gambaryan said in an interview. “We were waiting for a couple of hours, and it started getting a little weird.”

Gambaryan with CLICK HERE podcast host Dina Temple-Raston in December 2024. Image: Sean Powers/Recorded Future News

Gambaryan was there with a colleague named Nadeem Anjarwalla, a regional manager for Binance. Anjarwalla was younger and didn’t have a law enforcement background — he was more like Binance’s business guy for Africa. Both men thought they would be sitting down with Ribadu and other Nigerian officials to find more areas of cooperation, to see how they might work better together.

But the meeting with Ribadu never happened. Instead, eventually, several Nigerian officials filed into the room where they were sitting. And what Gambaryan found unsettling was that none of them were making eye contact. When the meeting did start, Gambaryan realized it was not what they had signed up for.

“One of the guys who is actually responsible [for my detention], he comes in, kind of slaps a folder on the table and starts saying, ‘You’ve destroyed the Nigerian economy,” Gambaryan recalled. They accused the two executives of helping Binance tank the naira, launder money and evade taxes. And then “they basically said, we are not gonna let you leave until this gets resolved.”

Among other things, the Nigerian officials said they wanted user records for every single Nigerian who was using the Binance platform. “They wanted everything, which is crazy,” Gambaryan said. “It’s like holding somebody from Facebook hostage, saying, give us every single Facebook user in Nigeria, or you can’t leave. They were trying to leverage me to get what they wanted — and that’s what all this was, from day one.”

The EFCC and Nigerian authorities declined to comment for this story.

Familiar charges half a world away

As a general matter, the Nigerian government has a history of being quick to level fines against foreign companies and seize their assets until they get them. In 2015, a South African telecom company got on the wrong side of the Nigerian government and was hit with a roster of multibillion-dollar fines for allegedly illegally repatriating money out of the country.

More recently, a Singaporean agricultural supply company was accused of being mixed up in a $50 billion foreign exchange fraud operation. In that case, the company did an internal investigation of its Nigerian operation and found no wrongdoing.

The Binance case was harder because there were no assets to seize or hold as collateral. By its very nature, the business model was ethereal. In a sense, Gambaryan and Anjarwalla became collateral.

The idea of grabbing the two Binance executives did not happen in a vacuum. A few months before Gamabaryan and Anjarwalla had traveled to Nigeria, there had been a landmark case against Binance brought by the U.S. Justice Department.

They had been investigating the company for years, and announced that they had reached a plea deal with Binance’s founder and then-CEO Changpeng Zhao, also known as CZ. He and the company agreed to plead guilty to a roster of federal charges, including flouting anti-money laundering laws and violating the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act. The company was fined $4.3 billion, one of the largest penalties the Justice Department has ever obtained from a corporate defendant in a criminal matter.

And while it is impossible to know if the case against Zhao and Binance planted the seed of an idea in the minds of Nigerian officials, it was hard not to notice that the charges they were leveling against Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were the very same ones that the U.S. had laid out in the plea agreement — tax evasion and money laundering related to lax oversight at the exchange. The difference, of course, was that Gambaryan and Anjarwalla weren’t founders of the company. They weren’t decision makers — they were mid-level executives. But they were in the crosshairs anyway.

An unexpected discovery

After meeting with Nigerian authorities, Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were taken to their hotel to pack their things and then to a compound in the capital city run by Nigeria’s National Security Agency. The building was supposed to house Ribadu, the national security adviser, but he preferred to live in his own home and left the property empty for official use.

Inside the Abuja safehouse where Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were initially held. Image: Tigran Gambaryan

Gambaryan said the conditions weren’t all that bad. Eventually, they had access to a phone so they could call family and their lawyers, and Gambaryan said Anjarwalla convinced the guards to pay for satellite TV so they could watch movies. The food, Gambaryan said, was also pretty good.

“There was a cook assigned to the house,” he said, adding that she was patient with their requests. “[Anjarwalla] kept asking for smoothies in the morning, and the cook would make him two smoothies every morning.”

The food might have been the only bright spot in what was otherwise a pretty dire situation. Weeks passed with little progress. There were some interrogations, demands for Nigerian trading data, an ask to disable Binance’s peer-to-peer trading — and officials suggested that Binance would need to pay a massive sum to settle the allegations and release Gambaryan and Anjarwalla.

Officials close to the case said that the Nigerian officials were talking about billions of dollars in fines. At one point, a government official said in a BBC interview that the fine would be at least $10 billion (more than twice the fine Binance agreed to in the U.S. case). The official later walked back their statement, but it was clear that Nigerian officials wanted a payment with lots of zeros at the end of it.

But everything went south for Gambaryan about a month into his detention. Their lawyers had let him and Anjarwalla know that the Nigerian government was preparing to formally charge them with tax evasion. Gambaryan went up to Anjarwalla’s room to talk to him about it.

“It was dark, the lights were out and I went up and knocked on his door, but there was no answer,” Gambaryan said. “I was like Nadeem? Nadeem? No response. So I walk into the room and I see like a mountain of blankets and pillows. There was a foot sticking out from underneath the blanket. So I pulled it… and it came off. It was a water bottle stuffed inside a sock.”

Gambaryan felt his heart sink. For weeks, he and Anjarwalla had been weathering the situation together. He thought surely Anjarwalla had left a note, an explanation somewhere. But Gambaryan couldn’t find one. And it was in that moment that Gambaryan realized it was going to be just him, by himself, against the government of Nigeria.

“I’m like, I’m alone,” Gambaryan recalled. “And so, I’m trying to figure out how do I handle this? What should I do?”

He figured he had minutes, at most, before the guards figured out that Anjarwalla had escaped and all hell would break loose. At the very least, Gambaryan would probably lose access to his phone and his only connection to the outside world. That’s when he tiptoed out to the courtyard, where no one could overhear him, pulled out his phone, and recorded the haunting video that made the rounds.

‘They treated me like Hannibal Lecter’

Two days after that video made its way out into the world, Nigerian authorities charged Gambaryan, Anjarwalla and Binance itself with tax evasion, laundering $35.4 million dollars in illegal transactions and operating without a license. And once Gambaryan was arraigned, he wasn’t sent back to the guest house with its satellite TV and chef. This time his treatment was much worse.

“They treated me like Hannibal Lecter when they were transporting me,” Gambaryan said, adding that while there wasn’t a hockey mask and straight jacket, like in the movie, there was a lot of security. “It was ridiculous. Like two trucks full of people with rifles, one in the front and one in the back, it was insane.”

Eventually, Gambaryan ended up in Kuje prison, one of the country’s largest and where it holds many ISIS-linked militants. Gambaryan was put in a special segregation wing for high-risk prisoners. “It was just a cell with no air conditioning, nothing. There was a bed frame, mattress, a fan and tons of cockroaches… everywhere.”

He noticed as soon as he walked into the prison that all the prisoners seemed to have a phone. “And I said to myself, how do I get me one of those?” The answer came a day or so later when a guard walked over to his cell, let himself in and sat on Gambaryan’s bed.

“He says like, ‘I’ll sell you a phone for $25,000,’” Gambaryan said. “I’m like what? And he says, ‘Yeah, you’re a Binance executive, you’re a billionaire, you can afford this.’” Gambaryan was dumbstruck. “You’ve got the wrong guy,” Gambaryan said. “And the guard goes, ‘OK, fine $5,000.’”

Gambaryan started to realize that while he was locked away, the Nigerian government had been painting a picture of him not only as the cause of Nigeria’s money problems — the inflation, the speculation — but also as a greedy billionaire and a crook. And Gambaryan was neither. He eventually got a phone for $300.

“The only thing that was kind of keeping me in the game was being able to talk to my family,” Gambaryan said. “I’m not sure if all of this has really messed me up, maybe it hasn’t come out yet — but I”m sure that if I didn’t have access to a phone everything would have been a lot worse.”

Gambaryan spent hours on video calls with his 10-year-old daughter. They’d talk while she played video games late into the night. And on those calls, he says he tried to pretend things were normal — that he was just on a long business trip. He later found out that she’d known all along — a Google search showed her that he was being detained in a Nigerian prison.

‘This is a show!’

Weeks turned into months. Gambaryan missed his son’s fifth birthday. He turned 40. And nothing progressed. Then one morning he woke up feeling kind of sick.

“It felt like food poisoning,” he said. It wasn’t food poisoning — it was malaria. And while the disease is treatable, if it isn’t addressed quickly it can be debilitating, even deadly.

Gambaryan wasn’t getting good care — he developed pneumonia and eventually became bedridden. It aggravated some of his back problems rendering him unable to walk and bound to a wheelchair. But when he was in public for court appearances, Nigerian officials wouldn’t let him use it. There were local journalists showing up in court, and Gambaryan said that officials thought pictures of him in a wheelchair would lead people to believe he wasn’t being well taken care of.

That’s when another video surfaced on social media. It was from last September and Gambaryan was in an echoey courthouse hallway, trying to make his way into the courtroom on a single crutch. He struggled to walk, and one of his legs dragged behind him. The video captures how frustrated he had become. “I don’t get it,” he kept shouting, “I don’t get it.”

A guard in brown fatigues tried to shuffle him into the courtroom, and when Gambaryan reached out for the guard’s, the guard pulled away. “He was told not to help me,” the video captured Gambaryan saying. “This is f***ed up. Why can’t I use a g****** wheelchair?”

Every few steps, Gambaryan had to rest against the wall. He shouted: “This is a show!”

The video, showing how much Gambaryan’s health had declined, went viral and it ended up being part of a cascade of events that finally seemed to shift things in Gambaryan’s favor.

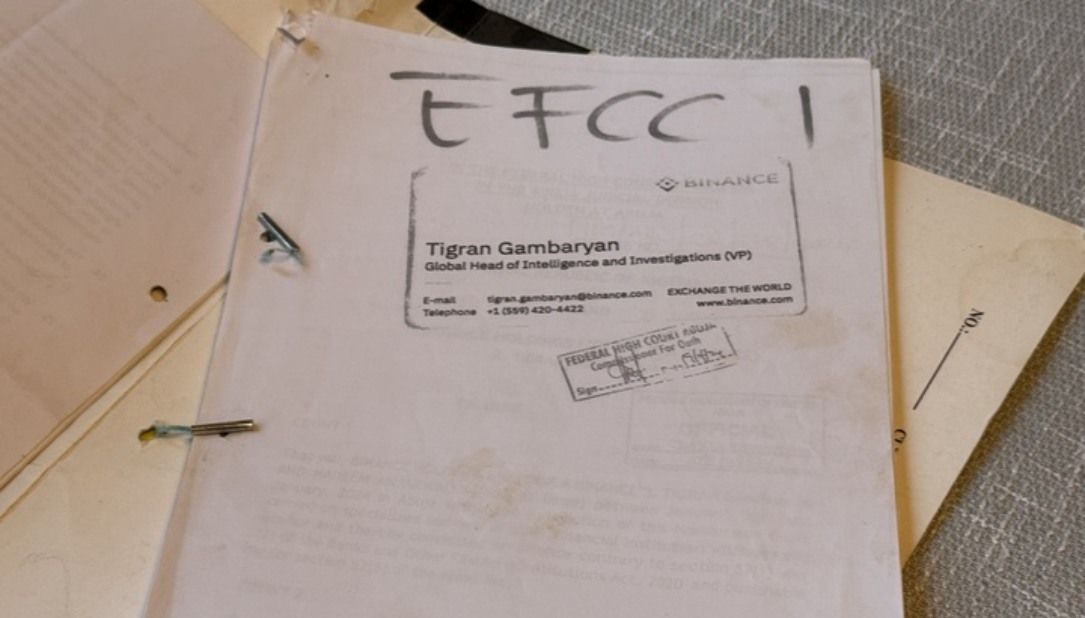

Exhibit A

The tide began to turn when Nigerian prosecutors actually began to present their case to the court. There wasn’t much of it. “The only evidence that they had in my charging documents was my business card,” Gambaryan said, offering up a photo copy of the case for examination. “In the entire charging records against me, my business card is the only evidence in there.”

“The only evidence that they had in my charging documents was my business card,” said Gambaryan. Image: Sean Powers/Recorded Future News

It was at that moment, it seems, that Gambaryan’s case really changed for the U.S. government. Sources at the Justice Department, White House and State Department declined to discuss the case in detail, and weren’t authorized to speak on the record, but left a clear impression that they weren’t in a rush to help resolve the situation. Maybe the U.S. saw Nigeria as a partner, or Nigeria’s case against Gambaryan at first blush seemed like the U.S.’s own case against Binance and its founder.

But after prosecutors submitted their evidence, it became clear that Nigeria’s case against Gambaryan was nothing like the one the U.S. had brought against the company. The U.S. case was years in the making. They had reams of evidence: emails, voice messages, transactions. Nigeria had none of that, and when this came out, U.S. officials seemed to kick it up a notch.

Full-court press

The U.S. strategy to get Gambaryan out was, it seems, pretty simple: A full-court diplomatic press. U.S. officials were told to bring up his case at the beginning of every meeting they had with Nigerian officials: with the foreign minister, the finance minister, the national security adviser, the minister of culture, the minister of sports.

This strategy went all the way to the top — all the way to then-President Joe Biden. According to four people close to the case who were not authorized to speak on the record, Biden was scheduled to meet with Nigerian President Bola Tinubu last September, at the UN General Assembly in New York. And U.S. officials apparently had signaled that Biden was going to talk about Gambaryan’s case in those meetings.

Tinubu ended up skipping the entire UN General Assembly. But Gambaryan’s health, the chorus of officials asking for his release and maybe embarrassment about the situation apparently became too much. The Nigerian government decided to release Gambaryan last October, on humanitarian grounds so he could get medical care.

Earlier, I spoke with President Tinubu of Nigeria to express my condolences on the floods impacting his country and my appreciation for his leadership in securing the humanitarian release of Tigran Gambaryan.

— President Biden Archived (@POTUS46Archive) October 29, 2024

We also spoke about the value of our partnership. pic.twitter.com/tsLGG0QLnf

Binance sent a private plane to pick him up. They flew him to Rome and then he took a commercial flight back home to the U.S. All told, he spent about eight months in detention. He’s still recovering from the medical issues related to malaria, and he still works at Binance. He’s no longer running the investigations team. He was away for so long, they brought in someone else to do the job in his absence.

Gambaryan says as far as he can tell, Binance doesn’t cooperate with Nigerian officials anymore, and neither do many other cryptocurrency companies. Binance did not respond to a request for comment.

People in Nigeria are still using cryptocurrency like crazy, but now it’s back to the Wild West and Gambaryan seems uninterested in helping them change that. When asked if he would ever go back to Nigeria, Gambaryan looked at his wife Yuki and started laughing. “I don’t think my wife would let me go back to Nigeria even if I wanted to… or even let me out of the house,” he said.

Gambaryan says he hasn’t spoken to Anjarwalla since his escape. Anjarwalla did not respond to a request for an interview.

Gambaryan said he thinks the escape wasn’t all that complicated. He suspects that Anjarwalla hopped the fence, got an Uber to the airport and caught the first flight out. The guards hadn’t searched his bags when they were sent to the guest house, and he had been carrying a second passport.

In November, Anjarwalla sent Gambaryan an email, saying he wanted to explain why he left. Gambaryan waited two months to respond. When he did, he said he told Anjarwalla: I don’t have that much to say to you. You could have at least given me a heads-up — I almost died in that prison.

Special thanks to Nick Fountain, Jess Jiang and Emma Peaslee with NPR’s Planet Money team.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”

Sean Powers

is a Senior Supervising Producer for the Click Here podcast. He came to the Recorded Future News from the Scripps Washington Bureau, where he was the lead producer of "Verified," an investigative podcast. Previously, he was in charge of podcasting at Georgia Public Broadcasting in Atlanta, where he helped launch and produced about a dozen shows.