Detained execs, a bold escape, and tax evasion charges: Nigeria takes aim at Binance

In cryptocurrency and law enforcement circles, Tigran Gambaryan is a bit of a legend.

As a special agent with the Internal Revenue Service he investigated financial crimes and he came to specialize in something a lot of agents, at least initially, didn’t quite understand: the blockchain.

Gambaryan became the Zelig of dark market takedowns, from Alpha Bay to the child porn marketplace Welcome to Video to the unmasking of Ross Ulbricht, the man behind the Silk Road market.

He was one of the first government investigators to figure out that an underlying assumption about cryptocurrency — that it was anonymous — just wasn’t true.

“When I started looking at cryptocurrency, I’m like, bitcoin is traceable. We can totally do this,” Gambaryan told me during an onstage interview at a cryptocurrency conference last year, explaining how he came to find patterns in the giant ledger that keeps track of all transactions. ”There's nothing special about me or any of the work that I did. It was just, we were there first … and it was just the realization that this was doable.”

Which is why this week — when Nigeria announced that it had charged Gambaryan, who now works for the cryptocurrency platform Binance, another of the company’s executives and the company itself with tax evasion — it rocked the crypto world. Nigeria’s Federal Inland Revenue Service said on Monday that Binance didn’t file tax returns or pay value added or corporate tax.

It was just the latest twist in a protracted dispute between Binance and Nigerian regulatory and central bank authorities. For months, Nigeria, which is in its worst economic crisis in decades, has been accusing Binance of manipulating the value of its currency, the naira, which has fallen some 40 percent in the first three months of the year. Binance has denied the allegations.

Tigran Gambaryan, left, and Nadeem Anjarwalla.

A month ago, Gambaryan, an American citizen, flew to Nigeria and met up with Binance’s regional manager for Africa, Nadeem Anjarwalla. The two were there to discuss the situation. After a few meetings that apparently didn’t go well, they were detained and their passports were seized.

They were taken to a government guest house run by the Office of the National Security Advisor, where they remained under guard while authorities said they were investigating Binance’s operations in Nigeria. Just a day before the charges were announced, Anjarwalla escaped, leaving Gambaryan at the government compound, where he remains under guard.

Bound for Nigeria

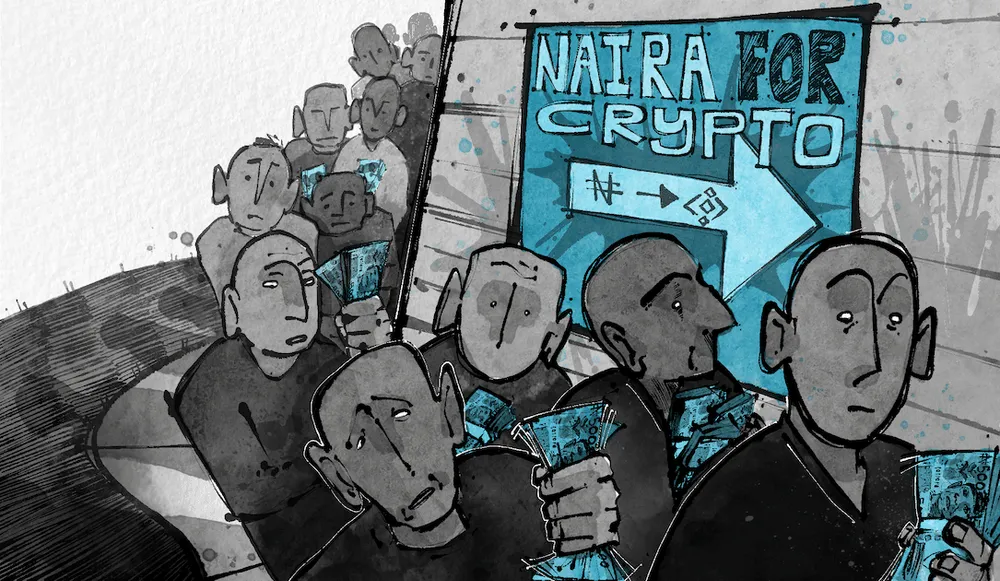

Looking back on it, Gambaryan’s almost evangelist belief in cryptocurrency may have made it inevitable that he’d find himself on a plane to Nigeria. It has the second-largest cryptocurrency adoption in the world, after India, and its cryptocurrency transactions topped $56.7 billion last year, according to Chainalaysis. Some 13 million Nigerians are thought to be trading cryptocurrencies on a regular basis.

You could be forgiven for thinking Nigeria’s embrace of cryptocurrency is inextricably linked to online scamming, which is a cottage industry there. In fact, Nigerians are such dominant crypto users for a much more pragmatic reason: Crypto has become a great hedge against inflation.

In developing economies, where the local currency fluctuates widely, ordinary people buy things that will hold their value as a way to stabilize their incomes. Traditionally, they bought U.S. dollars, but now they load up on cryptocurrency — often coins pegged to the dollar — because it is so easy to buy and sell. They don’t have to go into some back alley with a fist full of cash; they just have to log onto a cryptocurrency platform from their phones.

“Having so many Nigerian friends who are struggling day-to-day the real attraction of crypto is that when you are going to be certain that your country's currency is going to be worth less over the next week or month, you’re better off putting it in a safe place,” said Matthew Page, a non-resident Africa scholar at Chatham House, the London-based think tank. “Even with crypto, which is actually quite volatile, it is still in a safer place” than the naira.

The cryptocurrency platform of choice in Nigeria has been Binance.

Blaming Binance

There are two numbers that encapsulate the economic crisis in Nigeria. Inflation was up 30 percent in January from a year ago; and in the first three months of 2024, the value of the naira had fallen by 40 percent.

There are relatively straightforward explanations for both, and neither of them have much to do with cryptocurrency trading. First, corruption in Nigeria is endemic and only getting worse, which rattles confidence.The watchdog group Transparency International indexes countries based on perceived corruption and Nigeria ranked 145th out of 180 countries — slightly worse than Russia and a little better than Iran. .

The collapse in the value of the naira is even easier to track: It started to decline after the government announced in 2023 that it would end the currency’s peg to the U.S. dollar. At the time, government officials said they wanted the market to set the rate — to let market forces prevail — which, from this distance, appears to have been a mistake. Nigerians voted with their feet. Clearly the nation’s long history of economic mismanagement, corruption and monetary policy failures did the opposite of what the government had hoped for. The currency tanked.

Page and other researchers said the government was scrambling for someone else to blame for the crisis and landed pretty quickly on Binance, since cryptocurrency trading is pretty opaque to the average Nigerian.

It is important to note that Binance doesn’t set an exchange rate for the naira . It doesn’t have some giant pool of naira it uses to manipulate the currency’s value. Instead, the platform, which isn’t regulated in Nigeria, pairs buyers and sellers in peer-to-peer trading. The naira’s value is up to the two people in the transaction. But so many people were trading on the platform that its going rate for the naira became a kind of reference rate for the rest of the country.

That was among the topics of discussion that Gambaryan and Anjarwalla went to Nigeria to address, according to two people familiar with the situation.

A government pivot

It is unclear why Nigeria’s government decided to drop its currency manipulation allegations and decided instead to charge Binance and its two detained executives with tax evasion. Chatham House’s Page said it was likely a last resort.

“I think the Nigerian government really dug deep and pulled out the one set of charges they could really realistically levy against these individuals and the company at this time,” he said. “It was the old Al Capone strategy, right? If you can't get them on anything else, get them on tax evasion. And that's the situation that we’re seeing now.”

Observers also say Binance was singled out as a scapegoat for everything that has gone wrong with the Nigerian economy for another unrelated reason: Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice charged Binance and its former CEO with a roster of financial crimes, so it wasn’t a stretch for Nigeria to say it suspected some improprieties too. The U.S. government not only forced Binance’s founder to step down as CEO, but it also required Binance to pay a record $4.3 billion fine, which Chatham House’s Page said must have caught Nigeria’s eye.

If officials can slap a billion-dollar fine for back taxes on Binance, it could be a temporary cure for what ails them, he said. An unexpected infusion of cash could help with Nigeria’s cash-strapped economy. T. And the government has gone after big corporate targets before.

About eight years ago, a South African telecom company got on the wrong side of the Nigerian government and was hit with a roster of multibillion-dollar fines for allegedly illegally repatriating money out of the country. Last Fall, a Singaporean agricultural supply company was accused of being mixed up in a $50 billion foreign exchange fraud operation. In that case, the company did an internal investigation of its Nigerian operation and found no wrongdoing.

The Binance case is harder, Page said, because there are no assets to seize or hold as collateral because the business model is ethereal. “In the case of those other businesses, they had sort of brick-and-mortar assets,” he said. “They had very tangible business assets like a thousand cellphone towers spread across the country or a palm oil farm. Binance doesn’t have brick and mortar to seize in lieu of back taxes.”

So, in a sense, the Binance executives became collateral, even though neither Gambaryan nor Anjarwalla had anything to do with Binance’s tax collection or accounting. Remember, Gambaryan was an investigator. He was in Nigeria primarily to show regulators what kind of information they could tease out of the blockchain.

End games

Shortly before the Nigerian tax authority announced the tax evasion charges, Anjarwalla asked his guards at the guest house if he could go to a nearby mosque for prayers. Nadeem is Muslim, and it was the beginning of Ramadan. Allegedly guards accompanied him to the mosque and somehow, Anjerwalla just slipped away.

Exactly how that happened is still unclear. Nigerian government officials had taken both men’s passports when they detained them. Nigerian officials, when they confirmed the escape on Monday, told local media outlets that Nadeem must have used his Kenyan passport to board a flight. Apparently, he is now back in Kenya and Gambaryan is now on his own.

Before the escape, Gambaryan’s wife, Yuki, said she had been routinely talking and texting with her husband and now she can't communicate with him directly. She said he’s in a room in a guest house and isn’t allowed to leave. He’s been reading, watching TV and trying to work out. “Pushups and situps and stuff like that,” she said. “But I think those are the only things he is basically allowed to do.”

The people working the issue at Binance text him with updates, and “he's just kind of sitting there waiting for them to do something, which is really hard for him because he's a very antsy person,” she said. A high-energy person, stuck in a room, surrounded by guards, with very little information.

“I'm worried about his mental state more than anything,” she said. “And, you know, some days are good, but most days he just sounds very depressed. He says he feels hopeless. He says it feels like a nightmare he cannot wake up from, and I feel the same.”

She said the past month has been “the most exhausting, hardest days of my life, for sure.”

She still tries to go about her days, she says life doesn’t stop, she has to take care of the kids, make sure they’re doing their homework. “But it's getting harder and harder to stay positive and keep my spirits up,” she said.

They have a 5-year-old boy and a 10-year-old girl. “They are asking why hasn’t he come back, why is it taking so long,” she said. “He does travel a lot, but he's never been away for this long before.”

She says her daughter knows something is up. “I think she wants to ask me, but she chooses not to, because she's not ready to hear my answer,” she said. And what would she say if her daughter does ask? “I think I would just say that he is just not allowed to leave right now,” she said.

Binance has said that company officials are working with authorities to resolve the matter.

Page says it is pretty clear that money will need to change hands, whether it is a fine or a payment of back taxes. ”The standoff has now crystallized after the escape of one of the two detainees,” he said. “They’re embarrassed now and I think this could go on for months.”

Consider the recent case of Twitter. The government shut off the social media site, now known as X, after it deleted a tweet by the Nigerian president that threatened secessionist groups that were attacking government offices. The shutdown lasted seven months. “I think this is a country with an enormous degree of stubbornness, staying power and willingness to engage in brinksmanship,” Page said.

He says, even if the Nigerian government has a legitimate charge, the way it went about holding Binance to account has been ham-handed. “And in a way it's backfired on them,” he said. “I think that they have every right from a legal standpoint and a tax standpoint to hold this company accountable. I think that again, they've gone about it in the most thuggish way possible.”

Early in March before these most recent charges were filed, the BBC reported that a government minister had said Nigeria was going to levy a $10 billion fine against Binance as retribution for ruining the Nigerian economy. Days later, he insisted he’d been misunderstood.

But it’s very possible what the minister was doing was putting out an opening bid on just how much it will take to get Tigran Gambaryan back home.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”

Sean Powers

is a Senior Supervising Producer for the Click Here podcast. He came to the Recorded Future News from the Scripps Washington Bureau, where he was the lead producer of "Verified," an investigative podcast. Previously, he was in charge of podcasting at Georgia Public Broadcasting in Atlanta, where he helped launch and produced about a dozen shows.

Cat Schuknecht

Cat Schuknecht is a senior producer at the Click Here podcast. She’s previously worked at Gimlet Media, NPR, and on shows like Hidden Brain, and Reveal. She was a finalist for the WGA Awards in 2023, and stories she worked on have been up for DuPont Awards and Pulitzer Prizes. Cat also teaches audio storytelling at Loyola Marymount University.