After more than 200 takedowns, Meta confirms covert online campaigns have gone global

Six years on from the shock discovery of Russian interference during the 2016 presidential election — and in the face of considerable political pressure on social media firms to detect similar activity — Meta says it has now reached the milestone of taking down 200 such operations.

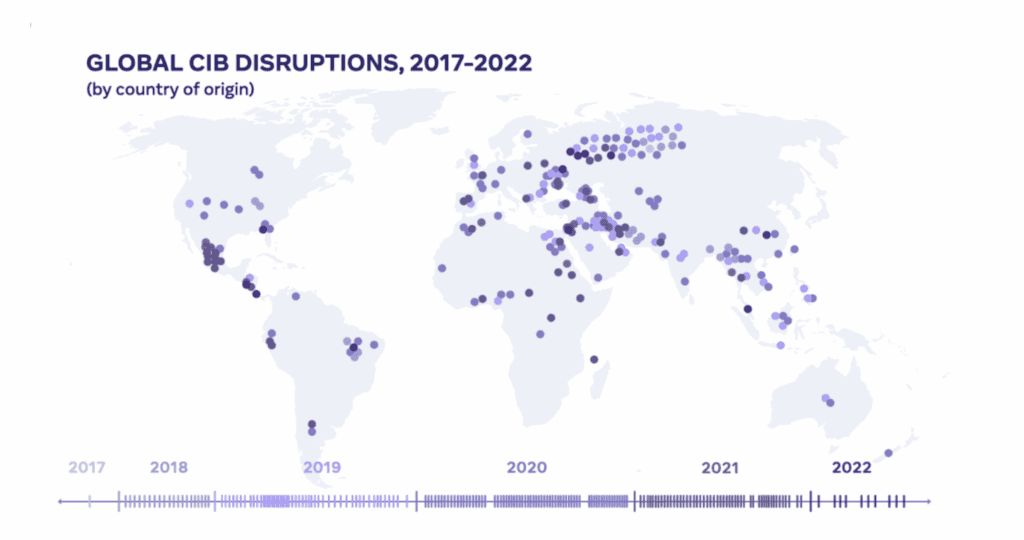

In a report published Thursday looking back at enforcement actions against these covert influence campaigns, Meta said the problem is now thoroughly global with “over 100 different countries, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe” being targeted, even if the United States, Ukraine, and United Kingdom remain the most common targets.

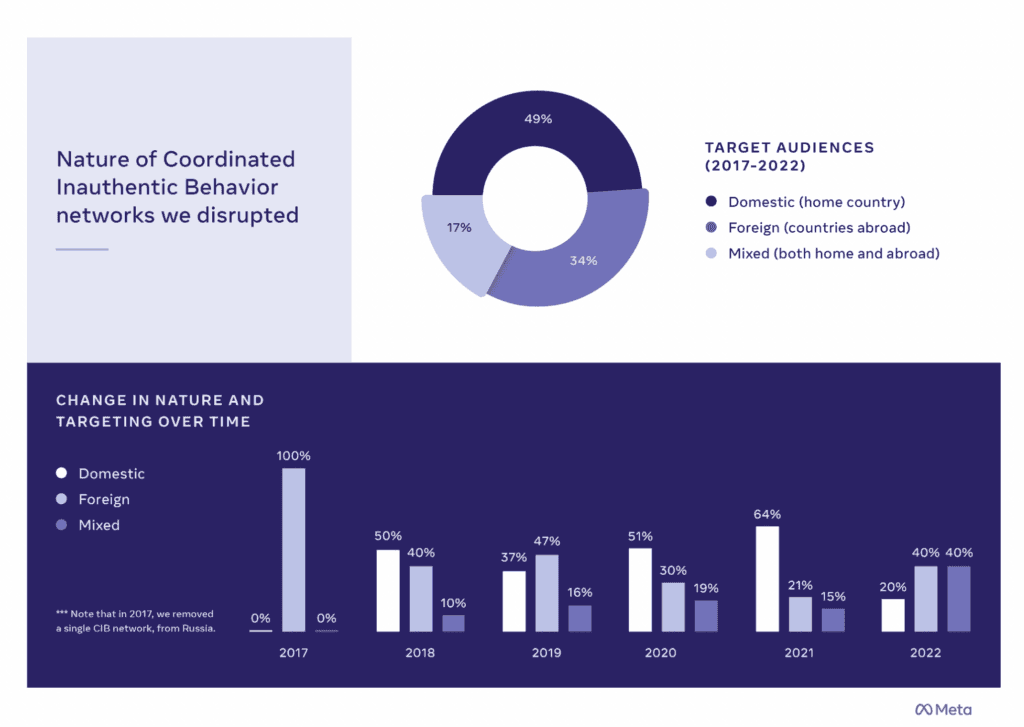

In a call with journalists, the company’s Head of Security Policy Nathaniel Gleicher said “while most of the public discourse focuses on foreign interference,” the majority of the coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) operations that Meta detected were actually targeting the same country where the CIB actors were operating.

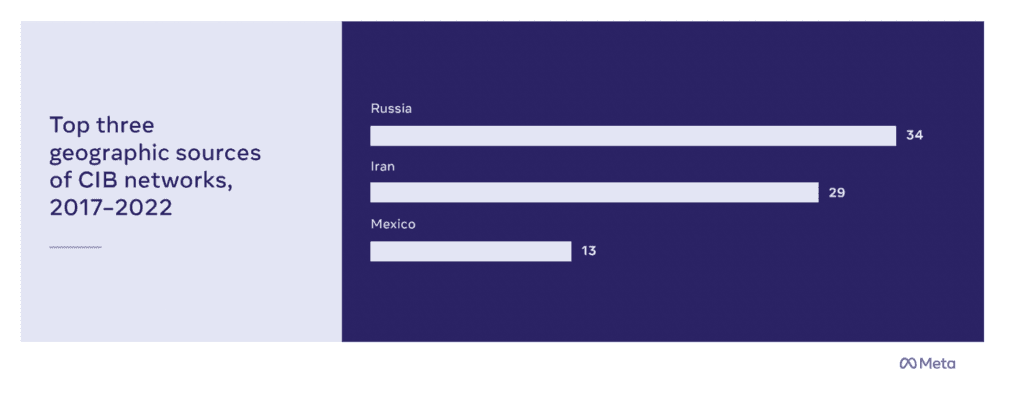

“Two thirds of the 200-plus networks we’ve removed focused either wholly or partially on their own domestic audience,” said Gleicher. Although the most common offenders — Russia and Iran — were operating internationally, the next most common location for CIB networks — Mexico — targeted people inside the country, with a particular focus on “extremely local audiences within a single state or even a particular town,” he added.

Meta said its investigations have resulted in the removal of CIB networks from 68 different countries using at least 42 languages “from Amharic to Urdu to Russian and Chinese.” Dismissing short-hand references to the so-called "Russian playbook," the company said it had seen a very wide range of tactics from networks originating in the country, whether they were run by people whom it “linked to the Russian military and military intelligence” or by marketing firms or “entities associated with a sanctioned Russian financier,” a reference to the oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin.

These tactics ranged from “spammy comments” on news articles and social media sites through to “running fictitious cross-platform media entities that hired real journalists to write for them” – in the latter case without the journalists themselves knowing they were actually working and being paid by Russian organizations.

Although it was Russian interference targeting the United States that had the biggest impact on the social media sector — almost certainly because most of the platforms are based in the U.S. and exposed to political pressure there — Meta said its investigations found that more operations from Russia were actually targeting Ukraine and Africa than were targeting America.

Regional discrepancies were also detected in who was targeting whom. The operations it took action against in Asia-Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America were almost always targeting domestic audiences, with 90% having a whole or partial focus inside their own countries.

In contrast, of the networks it took action against that were based in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, two thirds were wholly or partially focused on foreign audiences.

“Uniquely, the Gulf region was where covert influence operations from many different countries target each other, signaling these attempts at influence as an extension of geopolitics by other means,” the company found.

As an example, it identified “an Iranian network criticizing Saudi Arabia and the US; a network from Saudi Arabia criticizing Iran, Qatar, and Turkey; an operation from Egypt, Turkey and Morocco supporting Qatar and Turkey and criticizing Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the Egyptian government; and a network from Egypt supporting the UAE and criticizing Qatar and Turkey.”

Alongside the report on Thursday, Meta’s team has also attributed a Russian network which it tackled earlier this year — targeting “primarily Germany, and also France, Italy, Ukraine and the United Kingdom with narratives focused on the war in Ukraine” — to two specific Russian companies, Structura National Technology, and Social Design Agency (Агентство Социального Проектирования), which appear to be unconnected to previously identified organizations.

In that campaign, which ran from May to September, Russian operators ran a sprawling network of fake accounts on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Telegram and Twitter, as well as on the Russian-owned social networking service LiveJournal and popular petition platforms such as Avaaz and Change.org.

Gleicher told journalists that the vast majority of networks Meta was now disrupting were targeting multiple platforms, from those cited above but also including TikTok and Blogspot in English and Odnoklassniki and VKontankte in Russian.

During the call he also praised the work by Graphika and the Stanford Internet Observatory, which earlier this week revealed that Prigozhin-linked operators were manipulating audiences on alternative right-wing social media platforms, including Donald Trump’s Truth Social.

Meta said it had also seen a "rapid rise" in networks of fake accounts using profile photos created using generative adversarial networks (GAN), which are easily producible on websites such as thispersondoesnotexist.com, with more than two-thirds of all of the networks it tackled featuring GAN-generated profile pictures.

“Threat actors may see it as a way to make their fake accounts look more authentic and original,” reported Meta, but because its enforcement action focused “on behavior rather than the content posted by these networks” the use of these photos didn’t help the threat actors evade detection.

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative, now Virtual Routes. He can be reached securely using Signal on: AlexanderMartin.79