Yik Yak has returned — and so have reports of cyberbullying, students say

Yik Yak, an anonymous social media app that was shuttered in 2017 after coming under fire for facilitating cyberbullying, was resurrected last year with an emphasis on new protective measures including anti-bullying guardrails. But students and watchdog groups are already reporting instances of abuse, and say that the new safeguards aren’t enough to stop people from using the app for cyberbullying.

The app’s targeted consumers are college and high school students, allowing users to post or ‘Yak’ anonymously to others within a 5-mile radius. First launched in 2013 by Furman University students Tyler Droll and Brooks Buffington, the app experienced a rollercoaster of initial success followed by sharp criticism that would lead to its demise in 2017.

Advertised to be a safer and welcoming space, the app relaunched in August of 2021. New measures were put in place to ensure user safety including a downvote system. Posts that get 5 downvotes by other users are immediately removed from the platform. Yik Yak has implemented a one-strike-and-you’re-out policy that will ban the user from the app if the “violation is serious,” as stated on the website.

New app, new incidents

Last November, a freshman at the University of Vermont found out about a rumor that was circulating on Yik Yak.

“I was essentially sitting in my room one day and one of my friends up the hall sent me a post on Yik Yak that was about me. It essentially said, in a really fuzzy and benign way, that I assaulted someone,” said Cal McCandless, who recounted the incident in an interview with The Record earlier this month. McCandless describes himself as a student who is heavily involved with campus activities, whether it be performing with his band, running with the running club, or handling his classes’ Instagram account.

McCandless said he immediately contacted the police and Yik Yak to report the post and have it taken down, which wouldn’t end up happening for another 8 hours. The post was in violation of the app’s new privacy guidelines prohibiting the use of real names, McCandless said. “So as far as my experience goes, there are no terms of service, you can post anything,” he added.

The toll that the post took on McCandless’s mental health was severe, he added. “It was really really difficult to function as a normal person at school. I was not going to the gym. I was not running. I was walking outside between classes with my mask on. I would have my roommate go get me takeout containers for my meals.”

His experience was no longer just a personal issue, rather he saw it as a much larger issue concerning the nature of the app as being a “vehicle for vengeance.”

McCandless contacted UVM administration for further guidance with hopes to file a subpoena requesting information on the account linked to the post. His request was denied based on the notion that it was not a “threat,” he said.

Enrique Corredera, UVM News and Public Affairs Director, responded to a request for comment from The Record with a statement: “UVM is not in a position to ban the use of digital apps that are in the public domain.”

University faculty deferred McCandless to the student council to discuss removing the app from campus Wi-Fi. “When I met with the dean of faculty he said ‘if you can convince student council to come out against Yik Yak, then we can probably get it restricted,’” he said.

McCandless received a response from the Student Government Association (SGA) that was less than reassuring.

“The SGA felt that it would set a bad precedent if the app was restricted/banned on school wifi,” the email response said. The email goes on to state that Yik Yak is a popular and important space for students suffering from mental health issues to turn to. “I assure you, though, they wanted to make sure that your voice was still taken into consideration, and to not deny the fact that you have been personally affected by cyberbullying on Yik Yak,” the email concludes.

McCandless said he was never given the opportunity to speak or share his experience with the student council in person.

McCandless said it is ironic that SGA claimed Yik Yak helps those with mental health issues, when in reality it causes them. To him, Yik Yak’s existence is not just a personal issue, but an issue for the entire student body and students everywhere.

Yik Yak did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A growing problem

A simple Google search of the app supports McCandless’s theory that instances of threats, discrimination, and cyberbullying on Yik Yak are not isolated to UVM. Three weeks ago a student at LSU was arrested after posting about a campus shooting. Last week a student at Williams College shared that she was sexualized in a string of Yaks. The University of Maine Newsletter posted a letter on Monday about the use of the app to slander fellow students. The Oberlin Review published a letter concerning posts of anti-black racism. A juvenile was arrested in Fairfield, CT in January after posting violent threats directed at the school. The list goes on.

The common link between such instances: action is only taken by students who choose to go public with their experiences.

As the saying goes, history has a tendency of repeating itself: These incidents and McCandless’s experience echo a tragedy that took place years prior after the initial launch of Yik Yak.

A look at the past

In 2015 Grace Mann, a student at the University of Mary Washington and leader of the group Feminists United, was murdered by a member of the school’s rugby team following ongoing threats and harassment posted on Yik Yak by players on the team.

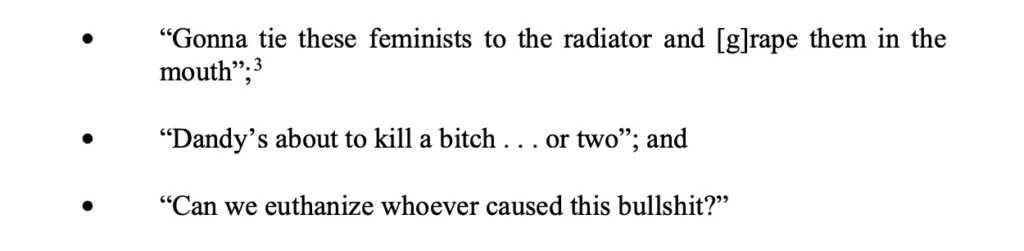

Prior to the incident, the rugby team had made chants that called for violence against women, including rape and necrophilia. As the leader of the feminist group, Mann was outspoken. Her activism resulted in nearly 700 harassing and threatening posts.

Mann and other members of the feminist group brought their concerns to university administrators who suggested they contact Yik Yak while also denying their request to ban the app on campus, citing the first amendment.

UMW’s Title IX coordinator, Leah Cox, responded to students in an email. “While the University has no recourse for such cyberbullying, Yik Yak and other social media sites do. If you find yourself the subject of an abusive or threatening comment on social media, please immediately file a report so that the site can take administrative action."

Yik Yak never responded to Feminists United.

Following the murder of Mann, the Feminist Majority Foundation, Feminists United on Campus, and five former UMW students filed a lawsuit against the university on account of “systemic failure to protect students from a sexually hostile school environment, sexual harassment, sex-based cyber assaults, and threats of physical and sexual violence, in violation of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (“Title IX”), and U.S. Constitution’s right to Equal Protection,” according to the Feminist Majority Foundation.

In 2017 the Eastern District Court of Virginia dismissed the plaintiffs' complaints due to the defendant’s limited control of what happens online. The plaintiffs appealed, resulting in the decision to vacate the prior dismissal of the Title IX sex discrimination claim due to the fact that UMW did have “disciplinary authority” over the harassers. In response to the claim that UMW had no control due to the anonymity of the posts, the judge said: “UMW cannot escape liability when it never took any action to try to identify the harassers” and “UMW could have acted to disable access to Yik Yak campus-wide as it has control over the activities that occur on their own network,” as cited in the Title IX Litigation Newsletter.

Yik Yak’s reputation sunk after increased instances of cyberbullying, harassment, discrimination, and violent threats transpired. Schools across the country began blocking access to the app on campus wifi as risks to the community persisted. By 2016 the number of downloads plummeted to 125,000, forcing the entrepreneurs to lay off 60 percent of their employees. The mobile payment company Square Inc. purchased the intellectual property and employee contracts for $1 million in April of 2017 and the app was finally shut down.

Although very different circumstances, clear similarities can be found between the obstacles faced by students who used Yik Yak back in 2015 at UMW and in the present day at UVM. There is a lack of accountability on the part of universities to handle threats posed by the cyber world — forcing students to fend for themselves.

Joseph Abboud, one of the lawyers who represented the Feminist Majority Foundation against UMW, spoke to The Record about the relaunch. “My personal reaction was, I don’t really see the point. When you bring back an app with the same name you are inviting the same kind of behavior.”

“I've seen things on Yik Yak that are just super racist or super sexist or homophobic, and I think: Why does this exist? How can this be a thing? It is so clear to me that there would be an improvement on the well-being of the community if the app were restricted, but it is really really hard to get done,” McCandless told The Record.

Emma Vail

Emma Vail is an editorial intern for The Record. She is currently studying anthropology and women, gender, and sexuality at Northeastern University. After creating her own blog in 2018, she decided to pursue journalism and further her experience by joining the team.