While Russian tanks attack, Ukrainian supporters hack back

Until a few weeks ago, Dmytro was a pretty average student.

Now the 18-year-old, who The Record is only identifying by first name for his protection, is volunteering to coordinate the defense of his country online from a bomb shelter in Kyiv.

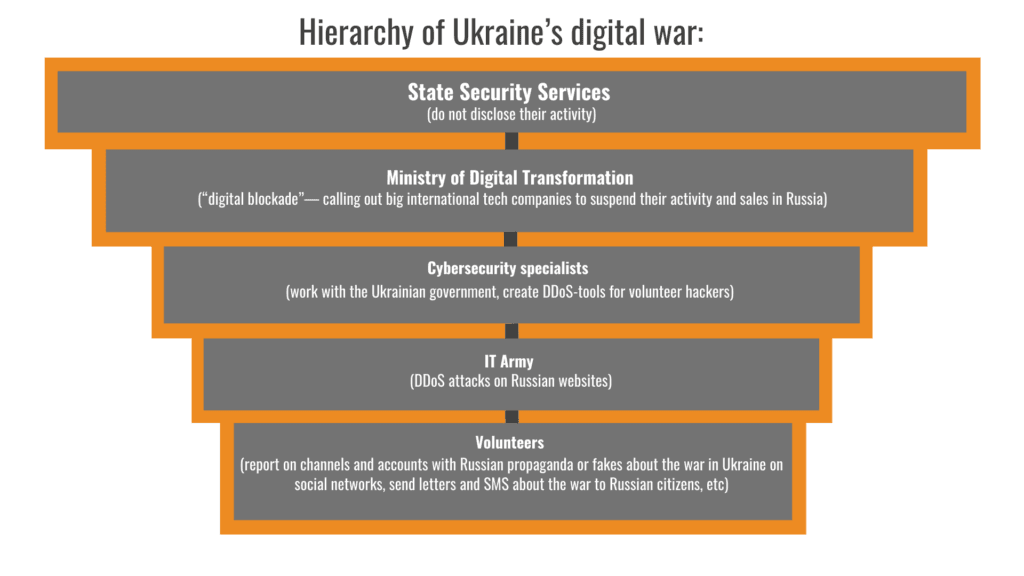

The Ukrainian government began recruiting local tech specialists for its so-called “cyber forces” unit even before the latest Russian invasion.

Its main purpose was to track and repel attacks in cyberspace, according to Serhii Demediuk, a top Ukrainian cybersecurity official.

But it was too late—Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24.

And now instead of professionally-trained cybersecurity specialists, Ukraine has turned for help to volunteers with different levels of IT skills organized in official and unofficial groups that can be hard to track — often “hacking back.”

“Everyone could join the Telegram channel (of the IT Army),” said Slava Banik, head of the development of e-services at the Ukrainian Ministry of Digital Transformation, referring to the official version, called the IT Army.

People online — some from Ukraine and some from abroad — are all contributing to a radically decentralized cyberwar landscape, where even playing a webgame can be contributing to the digital fight against the Russian invasion.

“We have already attracted over 300,000 specialists,” Banik said of the official IT Army efforts.

The IT Army’s main method of attack is to flood Russian websites with junk traffic, attempting to knock them offline. This method, known as distributed denial-of-service attacks, are one of the more simple types of digital attacks, and are frequently wielded by hacktivist groups.

Many attacks at least appear successful: volunteer hackers temporarily disrupted the work of Russian government websites, online banks, state-owned media, e-commerce platforms and streaming services websites, according to the IT Army’s public channel on the messaging app Telegram.

In response to these attacks, Russia appears to be deploying a defensive technical measure known as geofencing to block access to certain sites it controls, including its military website, from areas outside Russia’s sphere of influence, as previously reported by The Record.

And apart from this official army, there are multiple other groups claiming hacktivist allegiances, encouraging Ukrainians to counter Russian propaganda either by restricting access to its websites (DDoS attacks) or placing anti-war messages on their web pages (defacement attacks).

Some Western officials, however, call this battle “unethical” and fear that hacktivists’ attacks could get out of control and hurt ordinary people who are not involved in the war.

Volunteers, for example, may be in violation of local law, and tools being advertised to people wanting to join the front in cyberspace may also actually put them at risk, researchers warn.

Meanwhile, Russia’s digital attacks have been less severe than observers expected — perhaps, in part, as the military has focused on destroying communications infrastructure amidst the international outcry over reports of civilian attacks.

“It doesn't make sense for Russian hackers to attack digital infrastructure if they can drop a bomb on it,” said Yegor Aushev, CEO at the Kyiv-based cybersecurity firm Cyber Unit Technologies.

Tit for tat?

In the cyberwar with Russia, Ukraine has historically been a victim.

In 2015 its power grid was attacked by the Russian hacker group Sandworm. In 2017, over 12,500 computers used by Ukrainian telecom companies, banks, postal services, and government bodies were affected by a wiper tool NotPetya.

It’s also being slammed with similar DDoS attacks and even more destructive digital assaults now, according to Ukrainian officials.

From Feb. 15 to March 10, Ukraine recorded over 3,000 DDoS attacks on its websites, according to Ukraine’s state service responsible for information infrastructure protection.

Researchers from Slovakia-based cybersecurity firm ESET also reported a new type of destructive wiper malware—CaddyWiper— affecting computers in Ukraine.

#BREAKING #ESETresearch warns about the discovery of a 3rd destructive wiper deployed in Ukraine . We first observed this new malware we call #CaddyWiper today around 9h38 UTC. 1/7 pic.twitter.com/gVzzlT6AzN

— ESET Research (@ESETresearch) March 14, 2022

It erases user data, corrupts files on the computer by overwriting them with null byte characters, and makes them unrecoverable.

CaddyWiper is at least the third strain of wipers, which also include HermeticWiper and IsaacWiper, to have hit Ukraine since the beginning of the Russian invasion, according to ESET.

#BREAKING #ESETresearch continues to investigate the #HermeticWiper incident. We uncovered a worm component #HermeticWizard, used to spread the wiper in local networks. We also discovered another wiper, called #IsaacWiper deployed in #Ukraine. https://t.co/hBA2NKy5Lf 1/4 pic.twitter.com/NzPIsYiwWW

— ESET Research (@ESETresearch) March 1, 2022

The number of cyberattacks on Ukrainian computer systems started to rise before the invasion, according to data shared with The Record by Ukraine’s information security service.

Since then, local cybersecurity experts and state officials have been preparing for larger-scale attacks.

“In the worst-case scenario, Russia would deploy destructive attacks on energy, financial and transport infrastructure,” Demediuk told Forbes Ukraine. “People are dependent on these industries, so attacks on them provoke a lot of panic.”

But there was no single big cyberattack on Ukraine early in the invasion.

In fact, “Russian hackers are not as active now as expected,” Ukrainian top security official Yurii Shchyhol told The Record.

“Probably, they focus all their attention on the protection of their own information resources,” Shchyhol said.

But there have been multiple physical attacks on communications infrastructure in Ukraine as the latest assault continues, killing 902 and wounding 1,459 civilians as of March 19, according to the United Nations.

Cyberwarriors who hack back

The horror of the assault is fueling a “hack back” mentality among Ukraine’s leadership — reflecting a long-running global policy debate over when offensive cyber actions are appropriate.

“The thing is that we were under attack, for all these years, online. And we never fought back—we just defended ourselves,” said Alex Bornyakov, the country’s deputy minister for Digital Transformation in an interview with TechCrunch.

“This is, for the first time, us trying to show them how we feel when infrastructure is being attacked when you can’t just use your cards or government services and everything,” he added.

That mentality is also playing out in how Ukraine’s IT Army and other groups are responding around the world.

In the early days of the war, the main task of Ukrainian cyber volunteers was to paralyze the work of websites of Russian government agencies and large corporations, according to Banik.

On February 27, the Ukrainian IT Army hacked the website of the President of Russia, Russia's largest bank Sberbank, the Russian Ministry of Defense, and state-owned media websites.

But over time, volunteers changed their tactics and began to attack all sites that provide services to Russians—streaming services, marketplaces, Internet banking.

“This is the only way to make Russians wonder if their country's leadership is doing the right thing,” Banik told The Record.

As of March 8, the Ukrainian IT Army targeted at least 237 Russian websites, according to security professional Chris Partridge, who has been tracking their activity in his spare time.

“Most of the sites I’m tracking have been at least temporarily disrupted, imposing a cost on the site operator,” he told Forbes. “However, there are places where Ukraine seemingly can’t hit hard enough to shake a site . . . cryptocurrency sites using Cloudflare are almost totally up.”

Ukrainian volunteer hackers use various tools to knock Russian websites offline.

One of them is the app called disBalancer developed by Ukrainian startup Hacken that uses a cryptocurrency-based system to reward people for stress testing networks during normal times, but released a DDoS tool called "Liberator" geared towards this market. To use the program, the hackers have to mask their location using a VPN (a virtual private network) because the Russians block Ukrainian IP addresses.

It is impossible to see the app’s core code because the company doesn't use open-source DDoS methods.

“Our solution was initially designed for b2b needs, but when Russia invaded Ukraine, the team managed to use it to fight in a cyberwar,” the developers wrote in its Medium blog. “It is quite dangerous to spread it on open access.”

As of March 20, over 13,000 joined disBalancer’s English Telegram channel and nearly 6,000 joined the Ukrainian one.

Foreign users who spoke to The Record on condition of anonymity said that using disBalancer has become their morning routine.

“It is easy, but helps fight Russian propaganda,” one of them said.

| How does disBalancer work? When users launch the program, it begins to send a huge number of requests to one of the Russian sites. The more users run the program at the same time, the more requests the site receives. When there are too many requests, its server can't handle the voltage and the website shuts down. To restore, developers need to spend extra money. |

Another tool is an online game called Play for Ukraine, in which users need to move the tiles to reach the number 2048.

According to the game's developers, each user move creates a load on the Russian network and helps to shut down websites.

The game is available for everyone but mostly targets teenagers and children. “We know that young people try to help Ukraine win, but they often don’t know what to do,” the game’s developers wrote on their website.

Developers do not reveal which Russian websites they attack but said that most of them are from the list assigned to the Ukrainian IT army.

It’s also unclear at times who is behind many tools gaining popularity.

| How are everyday Ukrainians participating in the cyberwar against Russia? Since the beginning of the war, those Ukrainians who cannot fight the Russian army with weapons have joined the battle on the digital front. Some popular initiatives include: InstaPolice – reports Russian accounts with fakes on Instagram. Ukraine Resist – prepares tasks for people with different skills—psychologists, lawyers, copywriters, journalists StopRussiaChannel – reports Russian accounts with fakes on Instagram. Its bot, Letters of Truth, allows users to send letters to Russians describing what is really happening in Ukraine. Information Army – assigns tasks on social networks that help spread information about the war in Ukraine abroad. For example, users are encouraged to write comments about Ukraine on English-language websites. IT Army of Ukraine – organizes DDoS attacks on Russian websites. Kyiv Vibes – encourages people to like the tweets of public figures, politicians and influencers who support Ukraine. |

The main problem with these initiatives is the lack of coordination, cyber volunteers told the Record.

“New channels are constantly appearing on the Telegram and you don't know which one to trust,” said Dmytro, the former student in Kyiv.

Meanwhile, cybersecurity experts have warned about cyberattackers leveraging the interest in the digital fight against Russia. For example, cybersecurity firm Cisco Talos reported on March 10 that a fake version of disBalancer’s Liberator tool was spreading on Telegram that could spy on those who installed it.

This is concerning because volunteers often take their digital “marching orders” on Telegram or other public channels.

Professional cybersecurity experts, in turn, receive tasks from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, National Security and Defense Council, Ministry of Digital Transformation and Security Service, Aushev said.

According to him, trained hackers work with the IT Army so as not to interfere with each other's attacks.

Of all the cyberattacks carried out since the start of the invasion, the activity of the Anonymous hacking group stands out.

Anonymous members use Twitter to warn about the upcoming and successful attacks and talk via video messages, distorting their voices.

The group claimed to be responsible for the hack of Russian state TV channels, posting pro-Ukraine content including patriotic songs and images from the invasion.

JUST IN: #Russian state TV channels have been hacked by #Anonymous to broadcast the truth about what happens in #Ukraine. #OpRussia #OpKremlin #FckPutin #StandWithUkriane pic.twitter.com/vBq8pQnjPc

— Anonymous TV (@YourAnonTV) February 26, 2022

Since declaring the “cyberwar” on Russia, Anonymous said that it has hacked over 2,500 websites of Russian and Belarusian governments, state media outlets, banks, hospitals, airports and businesses.

Ukrainian government officials told The Record that they praise Anonymous’ efforts to support Ukraine, but have no links to this group.

Apart from Anonymous, at least 50 hacking groups, including Belarusian Cyber-Partisans and ContiLeaks supported Ukraine, according to a hacktivist with the user name Cyberknow.

At least 25 hacking groups, including SandWorm, Ghostwriter, and FancyBear, stand with Russia, according to Cyberknow.

Discomfort with chaos

While many countries condemn Russia's invasion of Ukraine, not all of them support mass attacks on Russian sites.

“Not only might it be illegal but it runs the risk of playing into Putin’s hands by enabling him to talk about ‘attacks from the west’,” Alan Woodward, a professor of cybersecurity at Surrey University, told the Guardian.

The U.S. government also warned that it was “prepared to respond” to digital counter attacks from Russia if the conflict expanded during the first few days of the war.

But compared to then the number of attacks and the list of targets for DDoS attacks has also decreased significantly, as Russian sites have introduced additional protection, according to the IT army.

“Such protection is difficult to overcome and it significantly reduces the list of our goals,” IT Army wrote on Telegram.

The U.S. tech company Cloudflare, which protects websites from DDoS attacks and helps them run faster, also decided to continue providing services to Russia.

According to the company’s CEO Matthew Prince, limiting access to information outside the country will make more vulnerable those who have used Cloudflare “to shield themselves as they have criticized the government.”

“Russia needs more internet access, not less,” he said in the official statement.

Global internet access is also enabling Ukraine’s IT Army to swell its ranks.

According to Aushev, nearly 40% of cyber-volunteers in his “legion” are foreigners.

However, joining the Ukrainian cyber army from the U.S. or the UK, for example, could break the law in those countries, experts warn.

According to Chris Grove, cybersecurity strategist at Nozomi Networks, hacking wars can have unintended consequences.

“Cyber weaponry can go off-target, for instance, and end up hitting services that normal citizens depend on,” he told VentureBeat.

Such incidents have occurred before, such as the apparent use of U.S. developed offensive cyber technologies in ransomware attacks as the technology trickled down the cybercrime economy.

But for Ukrainians, the ethics of the situation right now is clear.

"When you see bombs flying and children crying, you don't think about ethics," Aushev said.

Anonymous and other hacktivist groups also typically admit that what they’re doing is illegal and say that if someone catches them, they will be imprisoned.

"That's why we're anonymous—we don't want to be imprisoned for telling the truth," they wrote on Twitter.

Daryna Antoniuk

is a reporter for Recorded Future News based in Ukraine. She writes about cybersecurity startups, cyberattacks in Eastern Europe and the state of the cyberwar between Ukraine and Russia. She previously was a tech reporter for Forbes Ukraine. Her work has also been published at Sifted, The Kyiv Independent and The Kyiv Post.