When Ransomware Hits Rural America

Westmoreland, Kansas is the seat of Pottawatomie County and home to around 750 of its 25,000 residents. The town was a stop on the Oregon Trail and is littered with references to that network of covered wagons that carried hundreds of thousands of people across the American west in the mid-1800s.

But in recent weeks it was the site of another modern migration—this one of data, stolen from Pottawatomie County’s computers by cybercriminals who paralyzed its systems with ransomware and left some services inaccessible to residents for weeks.

The infiltration and the County’s reaction highlights the complicated economic, financial, and social factors at play when local government systems are compromised—including just how much information is at stake and how such attacks should be disclosed to the communities they serve.

Pottawatomie County discovered the attack on September 17, public information officer Becky Ryan told local television station WIBW a few days later. It ultimately paid the attackers off—but not the full amount, according to County officials.

The attackers originally demanded $1 million, but settled for $71,250 after “a successful negotiation” highlighting the County’s limited financial means and the strain of the Covid-19 pandemic, according to County statements.

Ransomware that encrypts computer systems and holds data hostage until the victim purchases a key to unlock it has become one of the most lucrative business models in cybercrime in recent years. Many sophisticated ransomware gangs now also steal information and leverage the threat of exposing sensitive data online to get victims to pay up. Some even appear to be working to auction off data from unsuccessful ransoms to other cybercriminals.

“In this case, the hackers demonstrated that they had seen some private data,” County Administrator Chad Kinsley said in a statement. ”We paid the ransom to protect our constituents and prevent that data from being made public,” Kinsley added.

Pottawatomie County says its systems are now restored, but even with paying off the ransom, the attack kept staff email access and some services, including the County’s online GIS mapping tool, offline for weeks. And with the investigation ongoing, the full extent of the breach or how much it will ultimately cost the local government and the people it serves remains unclear.

But such attacks now seem like an inevitability to some.

“It’s not a matter of if, it’s when,” said William Johnson, the County Administrator of Butler County—a rural area in the southeast of the state—which was the victim of a similar attack in 2017.

Counties with smaller populations, in particular, can be key lifelines to residents that may be protecting everything from health records to industrial systems that control utilities like water— often while facing similar risks to their urban counterparts, but with fewer resources.

National Association of Counties Chief Information Officer Rita Reynolds said defense often comes down to having those resources. “It’s whether or not they are equipped—if they have the right tools and people to protect the perimeter,” she added.

It’s hard to say just how many counties have been held hostage by ransomware, in part because disclosure may not be required unless they affect certain protected kinds of information such as health data.

Recorded Future has tracked nearly 400 known ransomware attacks targeting state and local government systems since 2013, including 70 this year. But the true figure is likely much higher.

Even back in 2017, Johnson said, Butler County’s insurance provider told him that it had already paid out well over 100 claims ransomware attacks on municipalities and counties that year.

MS-ISAC, an intelligence sharing group for state, local, tribal, and territorial governments with more than 2,500 members, detected 255 “ransomware incidents” across entities using their monitoring services from January through July of 2021, Center for Internet Security Senior Vice President for Operations & Security Services Josh Moulin told The Record. The group’s Cyber Incident Response Team assisted in 24 active attacks during the same period, according to Moulin.

Pott County

Getting to Westmoreland can feel a little bit like traveling back in time. The town is surrounded in all directions by rolling prairie, pasture, and farmland dotted by the occasional homestead.

For me, this landscape is home.

I grew up in Manhattan, Kansas—a land-grant university town mostly in neighboring Riley County (where most of my family still lives) that also spills into Pottawatomie. “Pott County,” as locals often call it, covers that bit of Manhattan, more than a dozen smaller communities including Wamego, St. Mary’s, and Westmoreland, as well as vast expanses of countryside covering 862 square miles in the northeast of the Sunflower State.

The morning after I got into Manhattan to visit family, my mom told me she had heard about the ransomware attack on local radio station KMAN.

The same day, September 28, the County posted to its website about their systems being offline

So I told my editor that work followed me home and hit the road.

Westmoreland is half an hour from my parents’ house by my preferred route—mostly blacktop, but with a few miles of rollercoastering over hills that will make you forget the state’s flat reputation until you’re back on pavement and greeted by a “Westmoreland Welcome” sign on an oversized wagon wheel.

I’ve been to the town at least half a dozen times before it was hit by ransomware. In fact, between road trips with family and to help a friend document all the state’s Post Offices, I’ve visited, conservatively, over a hundred Kansas communities.

That’s my frame of reference when I say that Westmoreland and Pottawatomie County at-large look like a rural success, or at least survival, story.

While populations in rural parts of the U.S. have declined for decades, Pottawatomie was the fastest growing county in Kansas in terms of population change between 2010 and 2020 according to Census data. But much of that growth was around Manhattan. Westmoreland actually saw a slight decline over the same period, losing 9 people.

And there are a few signs of decline around town, including the County’s historic 1884 limestone courthouse—now shuttered. And the County Health Department stopped providing “family planning and well women services” this summer.

However, the County Health Department's office is in a single story brick building on town’s main drag, which is filled with local businesses and has far fewer empty storefronts than many other Kansas similarly sized towns I’ve visited. With older cars, it could easily be a Norman Rockwell scene or The Andy Griffith show set. And just behind the abandoned courthouse is also the Pottawatomie County Justice Center, a much more modern limestone, metal, and glass structure.

I met County Sheriff Shane Jager the same day I first heard about the attack while taking pictures of the court buildings.

Jager is a third-generation law enforcement officer who has been with the force for decades, per his campaign website. He was helpful and polite. But I saw his smile clench when I introduced myself as news media covering the ransomware attack.

He was involved in responding to the attack, but mostly as a conduit to connect the county to the FBI, Jager told me—and gave me a card for follow-up questions. The County’s emergency response systems were on a separate network and not believed to be affected by the ransomware attacks, he added.

My first stop that day had been an old limestone school building that now houses most of the county’s offices.

I walked into the first public office I saw, where the County’s GIS operations are based, and noticed nearly all of the computers were off. I introduced myself as media covering the situation and was directed to Ryan.

Ryan was polite and offered me a written statement from the Department dated September 21st, but said she couldn’t tell me which specific services were being disrupted for residents. I or anyone else could, she said, check with each area to ask what services were available.

So, I did.

Some were transparent, but most redirected me back to Ryan.

Generally, the County could still carry out many operations in-person using pen and paper—they just took more time.

They even had access to some computers by that point, although not all. One office told me it had access to two working computers, down from the normal eight. But staff email was also inaccessible and no one seemed to have a timeline for when it might be back up.

“Hush, hush”

The next day, I started my reporting at the South 40 Cafe—an old school diner on the way into Westmoreland with a faded “Truckers Welcome” message painted on the side of the building, local history photos on the wall, and great breakfast food.

It’s exactly the kind of place that’s the beating heart of a small town where everybody knows everybody else—and their business.

So between bites of eggs and hashbrowns, I chatted with nearby tables about my own ties to the area, explained the weird coincidence of being around during the ransomware attack, and asked what they knew.

Most only had second- or third-hand knowledge. But much of the gossip I heard there and around town, including that the attackers wanted $1 million, was later verified by the County.

Others were directly impacted. One person, who requested to remain unnamed due to the closeness of the town, told me they tried to get tags for their car the previous week and couldn’t due to the computer problems—but the office didn’t tell them it was a cyberattack.

Several folks complained that the County was so “hush, hush” about the attack, or that it was trying to “sweep it under the rug.”

Some businesses affected were also reluctant to speak out. The president of one company I knew was impacted questioned me about my parents’ names and the street they live on before citing the importance of their relationship with the County as why they were declining to comment.

The County Health Department was also tight-lipped.

When I introduced myself as a reporter and asked if any of their services were affected by the cyberattack, the receptionist checked with her supervisor. After a short wait, they referred me back to Ryan. But I could book an appointment if I wanted, the receptionist confirmed.

Staff did not appear to be using their computers when I visited twice on Wednesday—first to ask for a comment and later that afternoon when I asked the receptionist about a joke tombstone in front of the office. (It was an anti-smoking pun.)

On Friday October 1st, KMAN reported and the County confirmed that it had paid an undisclosed sum to the attackers. I followed up with Ryan and Kinsley via their official email addresses as well as the gmail address the County was using to coordinate press statements to request an interview.

The messages to the official addresses bounced back to me the whole weekend. I also called the Clerk’s Office to ask about submitting state open records requests to the County via email and was told to fax them or physically return them in until staff had email access back.

But there was a County Commission meeting the following Monday, October 4th, so I headed back to Westmoreland to see how and if they would address the attacks.

For the first public stretch of the meeting, which lasted about an hour, they basically didn’t.

The three Commissioners, Chair Greg Riat and Vice Chair Pat Weixelman in-person as well as Dee McKee via Zoom, instead carried out the more routine business of running a county—debating everything from the consolidation of volunteer fire departments to how much gravel the roads need.

The County’s Counselor John Watt made the only apparent, opaque reference to the ransomware incident during the first public stretch of the meeting. “I had multiple meetings with county staff on multiple subjects over the course of the week that have kept me busy and I’ll just leave it at that,” he said.

Soon after, the Commission took a break before going into a series of private executive sessions that lasted nearly twice as long as the initial public meeting. Before heading outside to wait them out, I approached Weixelman—who represents the district covering Westmoreland—with questions about the attacks.

Weixelman told me he expected they would talk about the attack—and just how much to talk about it publicly—during the closed session and he might be available to discuss more later.

I asked if there was an email I could reach him for questions and he laughed, then pointed to a battered flip phone on the table in front of him.

“I don’t have email,” he said, adding I could call instead.

I waited outside with a local resident who attends every Commission meeting to ensure they don’t vote to tear down the old courthouse and KMAN News Director Brandon Peoples. The Sheriff joined us for a bit when he was summoned for part of the private session, but they weren’t ready for him yet.

So we talked about the weather, the town, and ransomware as we waited.

After the executive sessions, the public was briefly invited back in and told that the County would release an update on the ransomware incident at 2pm. I approached Kinsley, who said he would be declining interviews due to ongoing investigations, but the statement would be emailed to the press.

The ransomware attack was raised at the Commission meeting the past week, the Wamego Times reported, when County Treasurer Lisa Wright said the attack left operations “very limited.”

“The driver’s license is completely down, we can’t do taxes,” she said.

During that meeting, the Commissioners requested more public notice about the attack and Kinsley said that they had previously only released information to two media outlets because they were directed not to share information by the advisory team unless specifically requested, according to The Times.

The October 4th afternoon update revealed some details of the $71,250.00 payment and the County’s efforts so far, including that it had also spent $5,000 on “enhanced decryption software” it says was necessary to unlock the files and “$356.25 in exchange fees to facilitate the cyber currency payment."

In response to follow-up questions, the County declined to comment on what digital currency was used, citing the ongoing investigation, or say if information stored by the County’s Health Department was compromised.

“Once we know the extent of personal information involved, we will be able to take appropriate steps to protect our citizens. It is a time-consuming process, but we are committed to taking the time needed to do this right,” Kinsley said.

When I dropped off physical copies of open records requests after the Commission meeting, the staffer didn’t know when they might be able to receive them by email again. An update to the website also dated the 4th said all systems other than Driver’s Licenses were now operational and promised an update when that was fully restored.

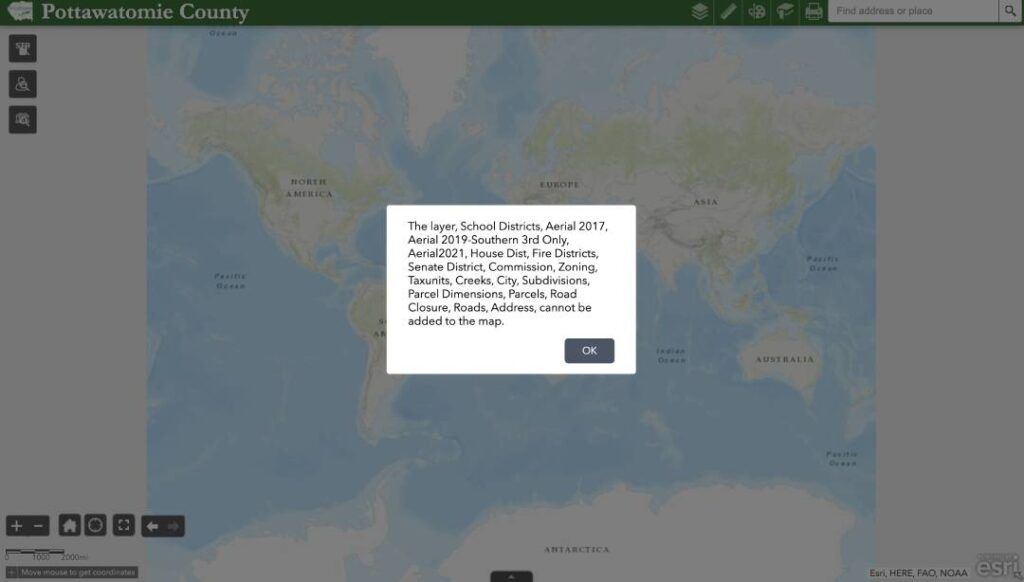

However, in response to follow-up questions from The Record, Pottawatomie County confirmed the next day that its GIS system remained down. An update to the County website on October 7 also confirmed it remained inoperational. It appeared restored by October 14.

Online GIS mapping tools are commonly relied internally to track things like revenue collection and provide public information key to the operation of many industries, including real estate, banking, and insurance. This information typically lives within its own database on its own server, potentially vulnerable to a network-wide attack, and can be more technically complex to restore.

Screenshots of attempts to load the online map during the outage showed failures of all apparent layers normally represented in the tool, including those labeled zoning, “taxunits,” and parcels among others.

Not alone

Pottawatomie County is far from alone in facing these challenges—or in choosing to pay up.

That’s what the IT consultants brought in by Butler County’s insurance provider, Traveler’s, recommended in 2017, according to Johnson. The attackers were paid around $27,000 in Bitcoin and the County had most things back up in four days, he said. After insurance coverage, the incident cost the County around $100,000 including costs to hire consultants and replace some systems they were unable to recover, Johnson said.

Butler had just added cybersecurity to their coverage the previous year, he added.

“We got pretty damn lucky,” Johnson said.

Butler County made a number of security changes, including requiring 2-factor authentication for all external sign-ons, in the aftermath and has since had to budget more for cybersecurity spending, including subscriptions to CrowdStrike endpoint protection, he said.

Johnson recalled that investigators said the attackers appeared to be based in Russia and had routed their web traffic through the Netherlands, but didn’t believe they were caught.

But one of the most curious parts of the experience, he said, was having a consultant tell him the County was lucky to get “an honest hacker”—one who was known for actually releasing systems when paid.

Not every attacker does.

Harrison County, West Virginia was hit with ransomware in 2019—with attackers first asking for $1,500 worth of cryptocurrency, but then refusing to turn over the key to unlock public records and asking for more, local television statement WDTV reported.

Attackers have also become more strategic.

“The MS-ISAC has seen evidence of cybercriminals doing research on the budgets of local and county governments before making their demand for a ransom. In one case, a county school district had a $40M ransom demand based on their public budget information of a $4B annual operating budget,” said Moulin.

For local governments victimized by these gangs and the people whose information they store, it can feel like they’ve been set up in a situation with impossible odds.

Pottawatomie County, for example, has an annual budget of around $36 million and lacked a dedicated IT staffer, let alone team, at the time of the recent attack, according to its website’s staff directory.

Manhattan-based vendor Fox Business Communications handled those services, Weixelman confirmed to KMAN. Fox Business Communications did not respond to a request for comment.

In Pottawatomie, the County said it paid for ransom out of its general fund, but $50,000 was reimbursed through insurance. The County’s coverage is through a KCAMP, a self-insurance pool for Kansas counties, according to a memo explaining the County’s insurance coverage obtained in response to a Kansas Open Records Act request by The Record.

The County policy includes coverage for “Privacy or Security Events” with a $10,000 deductible per claim and coverage for network interruptions and data access disruption kicks in after a 12 hour waiting period. Annual total liability for privacy or security incidents is capped at $1,000,000 and recovery cost claims are limited to $250,000.

There’s also up to $50,000 in coverage listed explicitly for “Cyber Extortion Expenses and Monies.”

Such coverage is key for counties, but becoming more expensive due to the rise in attacks, according to Reynolds.

It also appears to set up incentives at odds with the FBI’s general recommendation not to pay ransomware attackers because doing so funds further cybercrime and doesn’t guarantee the attackers will hold up their end of the bargain. (The FBI did not respond to The Record’s requests about their involvement in the Pottawatomie County investigation.)

But the issue can be complicated for victims because it may cost significantly more to recover systems from scratch than pay to get them back—and either way, they typically face additional costs to improve their overall security.

In an emailed October 18th statement, Ryan wrote that Pottawatomie County has completed its recovery efforts and “has now hardened defenses and installed additional sensors on all servers and machines to detect and better prevent further attacks.”

However, it remains unclear how long the full investigation will take, complicating just how much the County is willing or able to tell the public—including its citizens and the media.

“The challenge for you is that you want to put a human face on the rural small county, but they don’t want to look bad in the article,” Reynolds told me as I began reporting this story.

The Pottawatomie County’s public comments in the aftermath of the attack emphasized the positive, with its October 18th statement saying the attack had “minimal impact” on delivery of services to citizens.

“The County’s advisors have said that this is the most successful outcome they have seen, both in terms of the low ransom payment that was negotiated and the speed at which the negotiation was completed,” the statement said.

However, the County did not identify those advisors despite multiple requests from The Record. Staff did not directly address many specific questions about the scope of the attack, response costs to date, and other issues—in some cases, not acknowledging inquiries for days. A number of staff members also appeared visibly frustrated with my presence when I reported in person.

Given the circumstances, the aura of paranoia around me—an unfamiliar reporter asking pointed and sometimes technical questions—was understandable.

But the general lack of communication and transparency during the attack undermined some locals’ trust in the County. And the silence of some victimized counties can also make it harder for the sector to get the resources they need to protect themselves, according to Reynolds.

In Butler County, it’s easier to speak out now, years after the attack—and Johnson hopes more counties will be open about the struggles they face to stay secure.

“It’s something people need to share more about so we can be prepared, but we don’t,” he said.

For now, citizens in Pottawatomie are waiting for their county to share more with them about the attack.

Documents related to this story:

Pottawatomie County, Kansas KCAMP MEMORANDUM OF LIABILITY COVERAGE for 2021.

Butler County, Kansas’s Cybersecurity coverage for 2017 via Traveler’s Insurance.

Andrea Peterson

(they/them) is a longtime cybersecurity journalist who cut their teeth covering technology policy at ThinkProgress (RIP) and The Washington Post before doing deep-dive public records investigations at the Project on Government Oversight and American Oversight.