Ukraine’s drone whisperers: What the weapons are telling us

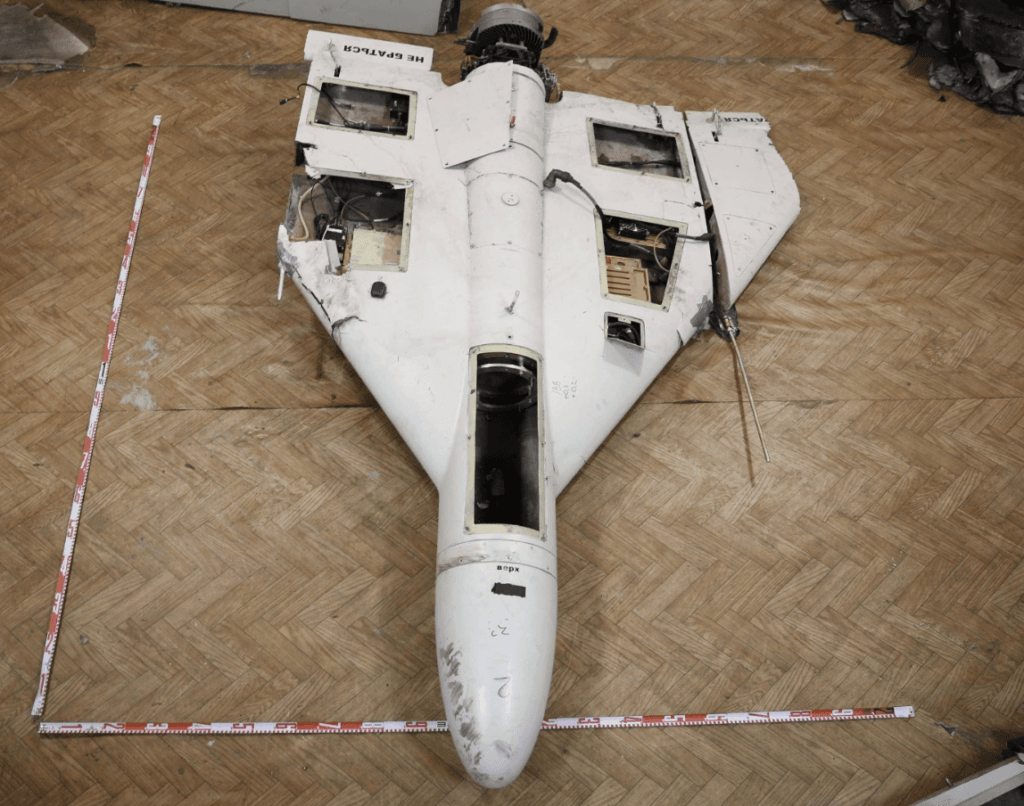

Drones have played an outsized role in the conflict in Ukraine – surveilling territory, dropping bombs, and crashing into buildings.

Russia launched some 600 drones in the last three months of 2022, according to estimates from the Ukrainian consultancy Molfar.

When the drones fall, or are shot down, Ukrainian forces retrieve them and hand them off to weapons investigators like Damien Spleeters, the deputy director of operations at Conflict Armament Research, a group that works with both governments and companies to piece together how weapons ended up on the battlefield.

While Iran has denied supplying Russia with the weapons, Spleeters’ work provides physical and irrefutable evidence to the contrary. It also highlights vulnerabilities in the supply chain that, regardless of sanctions, adversaries can exploit.

“Its whole chain of custody, all the hands it went through, how it arrived there and how it was used and all that,” he said, explaining what can be gleaned. “And I think through that, you can then tell a story about the conflict you are looking at, about the war you're looking at.”

The Click Here podcast sat down with Spleeters to discuss how investigators go about dissecting instruments of war and what clues their many parts provide.

The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

CLICK HERE: So how does someone end up becoming a weapons investigator?

DAMIEN SPLEETERS: I started as a journalist, actually, getting interested in weapons and how they're used and how they get into conflict areas … who sends them, who receives them and how they’re diverted in general. [I] got hired by [Conflict Armament Research] in 2014 as a field investigator to go to Syria and Iraq looking at Islamic State weapons.

CH: How did your work tracking ISIS weapons in Iraq and Syria inform what you’re doing now in Ukraine?

DS: ISIS was making weapons using commercial products and fertilizers and aluminum and all that. So we were going through their trash and looking at the remains of the packaging that they were using to make the homemade explosives. What we found was that there were very clear patterns, very clear networks of acquisition. They were turning to the same manufacturers for the same products.

CH: Because they wanted to make sure their bombs would work every time, and one way to do that is to use the same materials every time…

DS: Right. And now we are looking at Russia [and its missiles and drones] and standardization is also going on there. They want to use the same kind of proven components that they have tested and integrated into their systems.

CH: Can you give me a specific example of that kind of standardization?

DS: For example, we got four different models of Russian missiles that all use the same satellite navigation module in them. And that module is made of the same set of components from the same manufacturers.

And so that means that if you are able to impact the supply chain of this very particular set of technologies, you will impact four different models of Russian missiles.

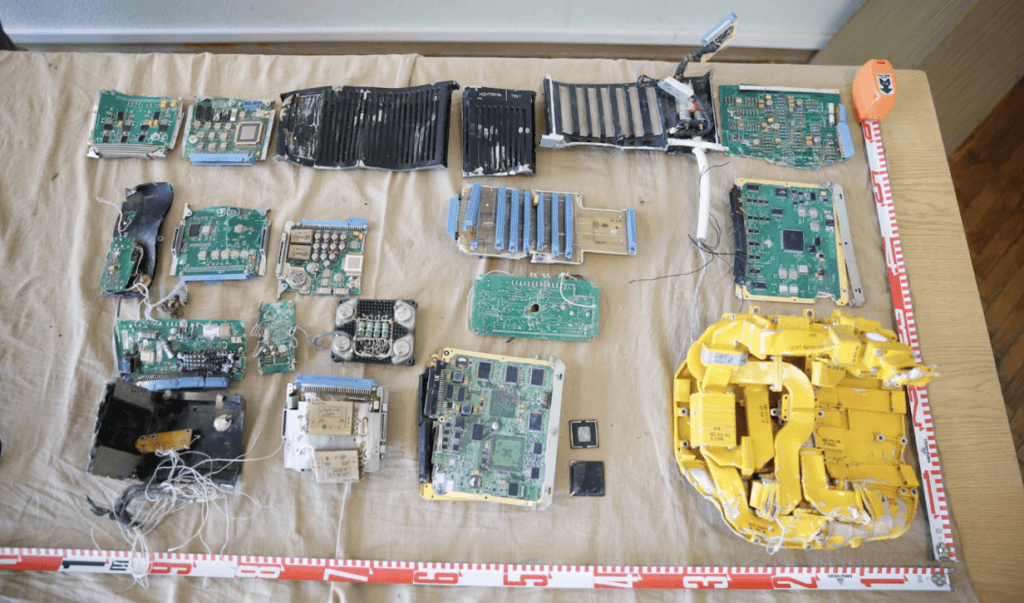

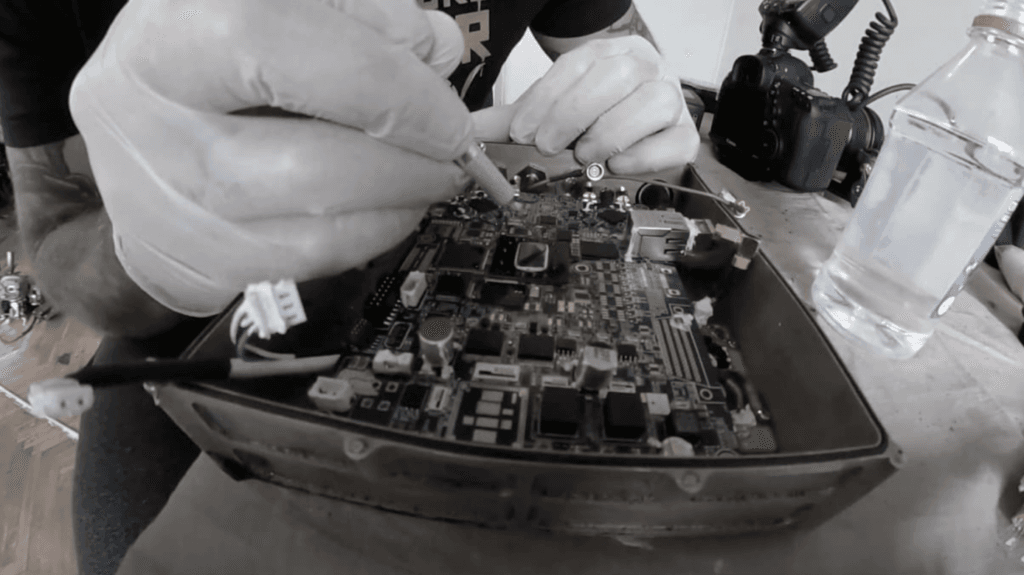

CH: So how do you go about actually taking apart these drones and missiles?

DS: We will gather as much contextual information as we can (where it was found, who found it, what was going on around it) and then we'll get to work with our tools — screwdrivers and wrenches and all that.

We'll open the system and very carefully disassemble screw by screw — and God knows that the Russians like to use a lot of screws — and then we'll just take very careful pictures of all the components until we are satisfied that the markings are readable. And we'll do that for the whole item, so that includes hundreds and hundreds of components.

CH: So when you dismantle an Iranian or Russian drone, what jumps out at you?

DS: The sheer amount of non-domestic technology. I was very surprised to see how dependent Russia and Iran are on components that are made by U.S. or European companies rather than on their own production. And it tells us something about the semiconductor supply chain in general and how globalized the world is.

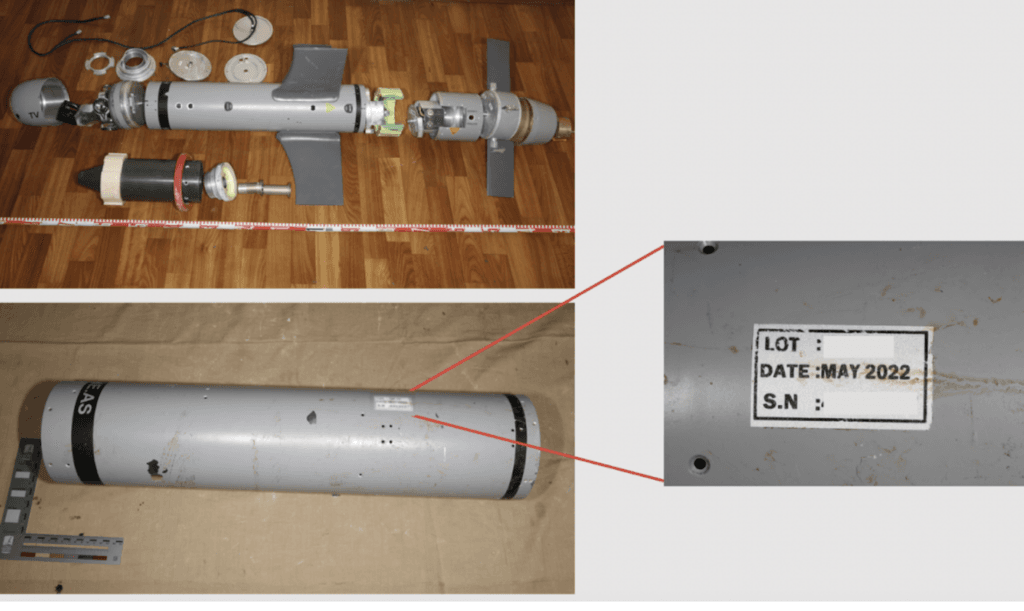

CH: When you examine something like a semiconductor, how do you go about tracing them back to specific manufacturers?

DS: The way it usually works with the semiconductor industry is that the type of marking you'll have on some chips denotes the week and year it was manufactured. And through that information, usually they can find records, a list of distributors that got the parts.

We will identify the same end users, the same distributors, and then, little by little, we'll uncover the acquisition networks that Russia and Iran have been using.

We have found, I think, about 150 different non-Russian manufacturers that were responsible in some ways for the production of components we found in Russian systems. And that number is 70 [non-Iranian manufacturers] for the Iranian system.

figcaption>Dissection of a damaged drone in Ukraine in November, 2022. (IMAGE: Conflict Armament Research)

figcaption>Dissection of a damaged drone in Ukraine in November, 2022. (IMAGE: Conflict Armament Research)

CH: When you uncover a specific manufacturer, what’s the next step?

DS: We know that naming a manufacturer and saying it's manufacturer “X” will not solve your problem. It will not give you the necessary information you need to shut down Russian acquisition networks. What you need is what comes after the manufacturer: what distributors were used, what end users it was intended for.

CH: So it’s the middle men and secondary distributors that are the problem, correct?

DS: Yeah, the nature of the semiconductor business means that [manufacturers] actually have very little visibility and control on their own supply chain.

It happens all at the distribution level. Like, once it’s left the factory and gone through a large distributor and then to a smaller regional one or to an intermediary there in the region or the country, that's usually where the issue was and where the true intention was kind of veiled.

And we need to secure the collaboration of the manufacturers. They have as much to gain in knowing what went wrong in their own supply chains as we do in order to mitigate future diversion.

CH: So does this mean all the sanctions against Iran and Russia are toothless?

DS: I think it's too early to say whether it has an effect or not. The vast majority of the products that we have found were actually produced between 2014 and 2021. So after the first set of sanctions.

So I think the more we go away from February 2022 [when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine], the more we’re likely to see sanctions starting to bite.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”