Exclusive: Ukraine says joint mission with US derailed Moscow’s cyberattacks

On a Wednesday afternoon in late September, the head of the cyber division of Ukraine’s intelligence service, Illia Vitiuk, sat down to discuss something that Ukraine had previously kept close to the vest — specifically how much a joint hunt forward operation with the U.S. military helped hobble Russian cyberattacks at the outset of the war.

“Indeed [Moscow’s] expectations for its cyberattacks were far beyond what actually happened,” Vitiuk told Click Here from the intelligence service's headquarters in Kyiv. The collaboration with U.S. Cyber Command started in the weeks before Russia’s invasion. “The GRU [Russian military intelligence] were responsible for these attacks and they thought that our infrastructure would be on its knees.”

Events didn’t unfold in quite the way Moscow had planned.

“They failed in bringing those kinds of disastrous effects” to bear, Vitiuk and other Ukrainian cyber officials told Click Here, because Ukraine had spent years hardening its systems against attack and because a team of cyber operators from the U.S. and Ukraine had secretly removed dozens of pieces of Russian malware from critical Ukrainian networks just weeks before the invasion.

This past summer, Click Here provided an exclusive insider view of a secret hunt forward operation. It began in December of 2021 and involved, among other things, flying some 40 operators from Cybercom into Ukraine to team up with local specialists, many of whom worked for Vitiuk at the Security Service of Ukraine, or SBU.

The SBU is the country’s primary intelligence, law enforcement, and security agency. Think of it as the CIA, the NSA and FBI all under one roof. Its headquarters sits on a highly fortified street in downtown Kyiv.

‘Nothing but a war crime’

As we approach we can see a maze of sandbags, guardhouses, gates and cement blocks. We’re greeted by men in uniform with Uzi machine guns hanging from their necks.

Once inside, there’s a twist of corridors. All the windows are covered against any blasts and there are fortifications inside as well. It looks like something you see in a movie about World War II. The place has a musty smell, like the carpets have been mopped and the damp never got out.

Illia Vitiuk is tall with a cropped beard and a shaved head. Unlike many of the other high-ranking officials in the current administration, he didn’t come from the tech sector. He came up through the ranks of the intelligence service, so he is what the U.S. intelligence community might call a company man. While protecting Ukraine from cyberattacks tops his list of responsibilities, he’s also quick to say that part of his job is investigating war crimes. “And we consider cyber aggression today — especially cyberattacks on civil infrastructure — to be nothing but a war crime,” he said.

It was precisely those threats against critical networks that animated a joint hunt forward operation in the first place.

This is the first time the Ukrainian side of this story is being told.

Early signs of trouble

Looking back on it, George Dubynski saw indications that Russia was planning to invade Ukraine months before it happened. He said back in late October of 2021, the Russian hackers he had been tracking were changing their behavior.

“We found some unusual activities, these hackers started to change their nicknames and had left their usual chat rooms,” Dubynski said. And while these were little signs, they were blinking red. “It was, you know, the first sign of some future attacks. And as we all saw, Russia started the cyber invasion before the kinetic one.”

Dubynski could see Russian hackers exploring Ukrainian systems, pinging for vulnerabilities. They were intimately familiar with the ins and outs of Ukraine’s critical networks.

“Unfortunately, the Russians, they know the architecture of our systems, and they know the equipment which was installed because a lot of it was installed in Soviet Union times,” Dubynski said. “For them it's easier to understand what is the weakest point for attacks and use them in some zero-day attack.”

Dubynski is more than just a casual observer of all this. He’s a deputy minister in Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation. It is one of nine agencies in charge of cybersecurity in Ukraine.

Dubynski found himself in Washington in the months before the war, asking for reinforcements. He wanted to persuade the U.S. to send cyber protection teams to Ukraine before the ground fighting started. U.S. Cyber Command said they could help.

‘Our big mistake’

In some sense, Ukraine had been girding for Moscow’s cyberwarfare for a decade. Long before the invasion, Kremlin-backed hackers had taken aim at Ukraine’s electrical grid, they had been blanketing its people with online misinformation, and they had been probing Ukrainian networks for years. Partly because of this long-running campaign, Ukraine set out to build one of Europe’s most sophisticated networks.

“We created plans, a cybersecurity strategy, we brought in lots of experts,” Dubynski said of the effort. But the one thing Ukraine hadn’t done, he said, was create a dedicated cyber force. A group of cyberwarriors who not only responded to attacks, but also worked to prevent them, like the U.S. Cyber National Mission Force at Cybercom, he said. “That was our big mistake.”

The Cyber National Mission Force has a variety of hunt teams in various stages of deployment all over the world. Typically, the cyber operations in the headlines tend to be offensive ones: A team shutters a troll farm in Eastern Europe, or hacks into the servers of a terrorist organization in Syria.

Hunt teams are different because they want to strike first: They go after foreign adversaries in networks before they have a chance to do any damage. The teams tend to focus on activities of the four nation-states considered the biggest threats: Russia, China, Iran and North Korea.

Operators in these so-called “defend forward” missions have suffered from the perception that they're more reactive than proactive — that they are waiting for something to happen before they move in. Turns out, this isn't the case.

“It's not a whack-a-mole,” one of the U.S. operators who went to Ukraine told Click Here back in June. He’s a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army and was, until recently, the deputy commander of a task force that specializes in hunting Russians in cyberspace. We agreed to use only his first name, Ryan, to protect his identity.

“We understand our adversary,” he said. “We understand the game and we look for the most likely place where we're, we are to find that game. We're looking for behaviors, we're looking for their capabilities and the things they don't want us to know.”

Pairing up

Putting together a hunt forward operation typically takes months. Embassies get involved, lawyers weigh in and there is a lot of back and forth to establish what networks can be searched, how they can be searched and how the teams will work together.

But there was no time for that in this case: Dubynski and Cybercom agreed on the scope of the Ukraine hunt forward mission in just 30 days. So quickly that just weeks after Dubynski went to D.C. to ask Cybercom to deploy a team, the first wave of American operators were on the ground in Kyiv.

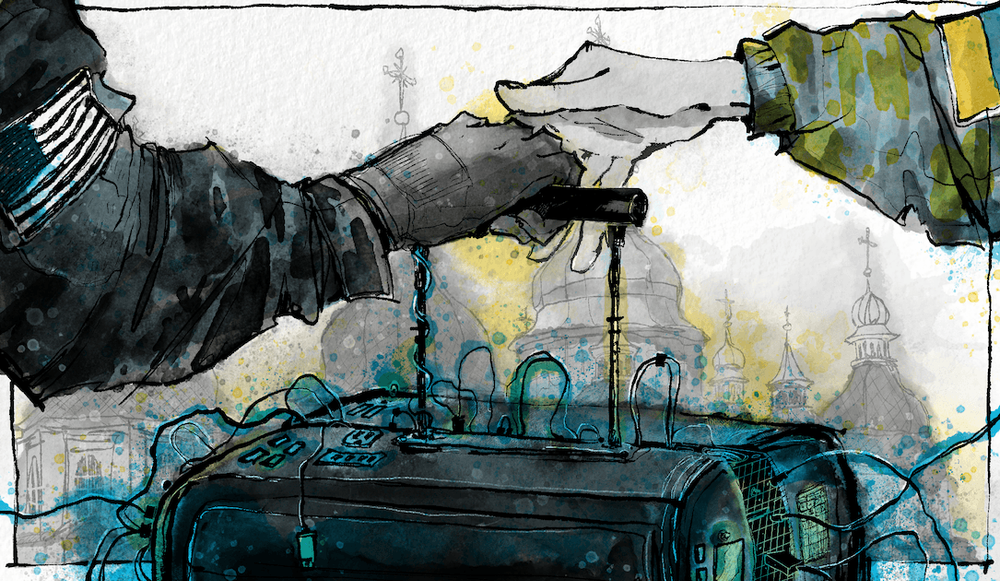

They wore civilian clothes, boarded commercial flights and personally carried the custom computers they would need to scour Ukrainian networks. Known as hunt kits, they’ve been specially designed to fit into the overhead compartments of commercial aircraft. It isn’t a checked bag anyone wanted to lose.

The hunt mission happened in an undisclosed location in Kyiv. “There was a big table, lots of computers, switches in the middle, a mass of boxes and wires and we put the network devices someplace where people weren’t going to step on them,” said Ryan. “Then we figured out who pairs up with whom and put that paper plan into action.”

Dubynski said it was a partnership: “The U.S. had done a lot of threat hunting, we understand the mindset and the language and specific tactics and together we were stronger than separately.”

A few weeks into the hunt they found one of the things they were looking for: Russian wiper malware. “This was my first time discovering something so complex in the wild,” a U.S. operator named Patrick said. Ukraine was his first deployment. “When I was there I was actually only 20, so not even old enough to drink back here in the states.”

Wiper malware is kind of what it sounds like: It erases the contents of a computer hard drive. Patrick said that it was complex and “the people who wrote it seemed to know exactly what they were doing.” It was designed to look like ransomware. “So it would pop up a little message on screen saying, you know, you can pay X amount to get your files back.”

But the more Patrick and the Ukrainians dug into it, the more they realized that it was not your garden variety ransomware, in which criminals lock up your data and demand money to get it back. “It became obvious that there was no method for this to reverse the encryption,” Patrick said. “At the end of the day, you weren't getting your files back, period. It was designed to destroy them.”

With more than a month to go before the invasion, Ukraine found itself on the receiving end of dozens of these kinds of attacks. American cyber teams wouldn’t tell us how much malware they ended up finding. Dubynski was more forthcoming. “They found, as far as I can remember, 90 malware samples” dropped in Ukraine’s critical networks, he said.

The number is staggering: 90 examples of malicious code the Russians had created to wreak havoc on Ukrainian infrastructure. It would be like preemptively discovering 90 different previously unknown types of Russian bombs that they could study, defuse and prevent from going off.

Illia Vitiuk speaks at the iForum conference in August 2023 in Kyiv. Image: Daryna Antoniuk / The Record

We asked Vitiuk, the SBU cyber leader, if the hunt team’s discoveries meant that it was only after the Russians started a cyberattack — essentially pushing the launch button — that they realized their best laid plans had been foiled. Ukraine had once again defied expectations.

“I’ll be frank with you. Sometimes we witnessed just what you suggest,” he said. There were some attacks that were successful, but many had been derailed by the hunt forward operation. VItiuk said that the Russian war plan failed in cyberspace in much the same way it did on the ground.

Russian forces had expected to get all the way to Kyiv, he said, and it didn’t happen. “It is just the same story with cyber, this was not the result they were actually counting on,” he said, adding that it appeared that when the Russians realized a lot of their prepositioned malware was gone, they became desperate and began going after random targets.

“We saw that they were hunting high and low, so there were attacks on pharmacy shops, on toy stores. They were attacking everything they could find,” he said, adding that they haven’t given up. He and his SBU team continue to respond to at least a dozen serious cyber events every day.

“Most of these attacks, we do manage to stop in its initial stages,” he said.

Case in point: an attack they discovered a few months ago that had been previously unreported. Ukraine found Russian hackers were trying to crack into a company that supplied telemetry equipment to water and gas utilities. Vitiuk declined to name the company or the specific utilities the Russians targeted.

Telemetry equipment has lots of uses: It might monitor the quality of water to ensure it has the right mix of chemicals or is drinkable. For gas pipelines it might measure pressure or temperature to warn about a potential explosion.

Vitiuk said the telemetry company periodically sends out software updates — the same way your iPhone does — and the SBU hunt teams saw Russian hackers trying to sneak malware into an update, hoping to slip into utility systems undetected. Vitiuk said had the Russians been successful, “literally they could have stopped the flow of water and the flow of gas,” creating a “catastrophe” in Ukraine’s civil infrastructure.

When we asked how they spotted the attack, Vitiuk declined to provide more detail. “You should understand,” he said, “that there are some things that I cannot reveal because some operations are still in action, or I cannot reveal some successful stories because our adversary can't understand where we are inside and what we understand, what we see.”

‘Creative people like freedom’

Most observers of the conflict in Ukraine will tell you three things likely contributed to the absence of any single spectacular cyberattack in the early days of the fight.

The first was Russian hubris. Prewar estimates suggested that Ukraine would be able to hold onto Kyiv for just a few days. Some suggest that Russia didn’t launch a crippling cyberattack on the electrical grid on the assumption it would only anger the people they were preparing to rule.

The second was that Russia had indeed planned attacks but they didn’t materialize either because of the secret work the Ukrainians did with Cybercom before the war or maybe because Ukrainians have literally been hardening their networks for a decade in anticipation of a conflict just like this one.

The third variable involves people — both Russians and Ukrainians. The Ministry of Digital Transformation’s Dubynski said Russia is struggling under a brain drain. Its best hackers have disappeared. “Many of them just all left Russia,” he said, “or are trying to distance themselves from what the Russian government is doing,” which has allowed Ukraine to leverage another, slightly intangible, advantage: creativity.

“To be creative you need creative people,” he said. Creative people like freedom. But Russia does not like freedom.” That creativity, he said, explains so much about the war — it isn’t something that you can buy, it has to just come from the people themselves. “Creativity,” he said, “is Ukraine’s secret weapon.”

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”

Sean Powers

is a Senior Supervising Producer for the Click Here podcast. He came to the Recorded Future News from the Scripps Washington Bureau, where he was the lead producer of "Verified," an investigative podcast. Previously, he was in charge of podcasting at Georgia Public Broadcasting in Atlanta, where he helped launch and produced about a dozen shows.

Daryna Antoniuk

is a reporter for Recorded Future News based in Ukraine. She writes about cybersecurity startups, cyberattacks in Eastern Europe and the state of the cyberwar between Ukraine and Russia. She previously was a tech reporter for Forbes Ukraine. Her work has also been published at Sifted, The Kyiv Independent and The Kyiv Post.