The Yanluowang ransomware group in their own words

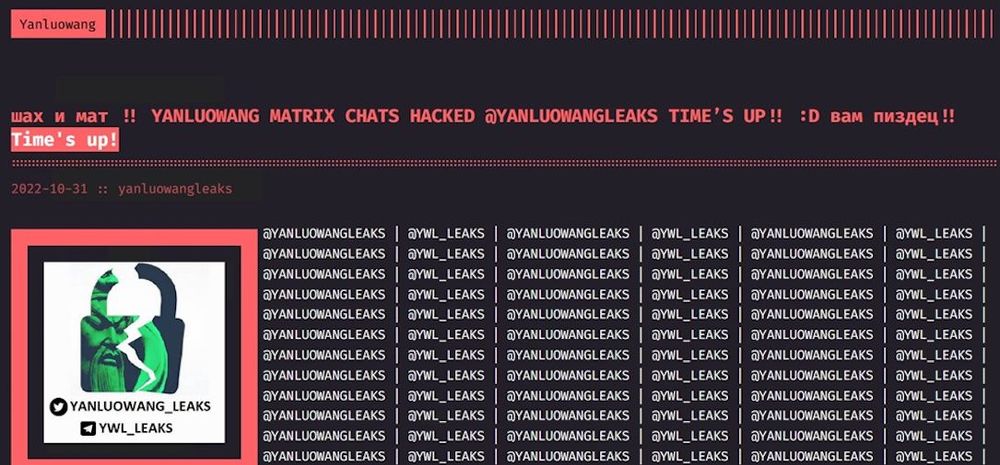

On Halloween, a message appeared on the Yanluowang ransomware group’s extortion site: “Check and mate! Yanluowang Matrix chat hacked,” it began. “Time’s up;) you screwed!!”

It announced that the contents of one of the group’s discussion channels – some 2,700 messages sent between January and September 2022 – had been breached and was now uploaded to a leak site that allowed researchers, law enforcement, and even competitors to understand how the group was organized, how it interacted with other ransomware actors, and who might be in charge.

“We wanted to dig into the internal chats and figure out what we could locate there — what their TTPs [tactics, techniques, and procedures] tradecraft is, was there any collaboration with other ransomware families, “said Jambul Tologonov, a researcher at the cybersecurity firm Trellix. “That’s what my mindset was when I started the investigation, and the first thing I noticed was that their conversations were all in Russian.”

The finding confirmed something researchers had long suspected: Yanluowang members were just masquerading as Chinese hackers. The name was a ruse. Cybersecurity firm Symantec first discovered the group in October 2021, and it soon got a reputation: It was clearly human-run, was reasonably skilled, and it targeted Western companies. Two of its most infamous targets: Cisco and Walmart.

Chat logs are particularly popular with researchers and law enforcement because they can provide a window into the inner workings of a cybercriminal enterprise. Members speak freely, they have their guard down, and it doesn’t take much effort to work out who is in charge.

Earlier this year, the chat logs from a Russian-speaking ransomware group named Conti were leaked, and the trove provided all kinds of clues about how they were organized, what kinds of hacking tools they used, and the relationships they had with other hacking groups and Russian law enforcement. In that case, there were tens of thousands of chat logs to comb through. In comparison, the Yanluowang cache is relatively small.

As soon as the leak message popped up on the group’s TOR site — which uses open-source software to conceal visitors’ location and identities — and Tologonov could confirm it was real, he downloaded messages and began digging in. He said he usually begins by writing a Python script to pre-process the messages to make them easier to read. Then, he puts them in chronological order so he can follow the message thread.

“It allows me to get a good understanding of who’s talking with whom,” Tologonov said.

Based on the messages, it was clear someone with the name “Saint” was a high-ranking member of the group. In mid-February, Saint was telling someone named coder0 how to set up a leak page on TOR, short for The Onion Router. “Felix is a tester,” he wrote. “I pay his salary for that.”

Saint tasked another penetration tester with looking at the TOR administrator panel. “If you need to test something, write here to Felix,” the chat continued. Small details, to be sure, but data points that can be gathered together to get a sense of the group.

Ready Coder One

Tologonov gleaned other clues. Coder0, for example, seemed to be the group’s developer of a Windows-based ransomware strain, and he had a team of coders under him. Another hacker named Kilanas is allegedly a member at the Russian Federation Ministry of Defense.

Saint appears to have gotten around as well. Tologonov said that he tracked down some of his other aliases, including “sailormorgan32.”

“That was a very interesting discovery because last year someone named sailormorgan32 posted on the dark web that they’d been part of a group that hacked SonicWall,” Tologonov said, referring to last year’s attack on the company that makes firewalls for virtual private networks.

“He claimed that they managed to get $5 million from the organization,” Tologonov said. “We don't know if the claim is true or not, but in the conversation someone asks him [Saint], isn’t sailormorgan32 one of your monikers? And he says, indeed, it is mine. It's time for me to go sleep.”

The chats also provide insight into how various ransomware groups are pooling resources and working together.

Hello Guki. HelloKitty.

The chats also reveal links to other groups, like the infamous HelloKitty ransomware gang, which the FBI believes to be based in Ukraine. A hacker named Guki, who’s thought to be a HelloKitty member, appeared in the chats this May, complaining about having dozens of working credentials – usernames and passwords – but lacking the manpower to exploit them all.

“That’s why I’m reaching out to you,” the chat reads. “Maybe we can work together on further compromises.” He also mentions that they are developing everything on their own. When Saint asked him what software his group was using, Guki replied: “the same as before, kittens.”

Researchers love to analyze these kinds of leaked chats because it allows them to observe hackers with their guard down. What doesn’t make sense, though, given what these hackers are doing for work, is that they don’t encrypt their messages. You’d think that would be Hacker 101. Tologonov said that surprises him, too.

“That was also an interesting thing for me,” he said. “You’d think some part of the messages would have been encrypted which would have made it hard for me as a security researcher to reconstruct all of this. I’d have trouble putting it all in context. But because it isn’t encrypted as soon as I pre-process the messages and put it in chronological order, as a Russian speaker, it is easy to read it.”

John Fokker, head of threat intelligence at Trellix, did a lot of research when the Conti Leaks came out earlier this year. He thinks the Yanluowang leaks came from a private server the group set up to speak among themselves and he believes they fell prey to a common problem: they trusted the technology.

“When people start trusting technology and they trust the encryption to give them safety, they will let their guard down and you get these interesting chats,” he said. “As a researcher from the sidelines, I’m always very eager to receive these chats because it really ties the Russian cybercriminal ecoclimate together. You can see how Yanluowang is tied to other organizations.”

Fokker said he and his researchers had always had a gut feeling that these ransomware groups weren’t huge – that there was a hardcore group that does this and they know about each other. “And it’s very interesting to read things [just as] they read our research — they look at other busts, and they watch other crime groups. It gives us a lot of insight.”

The question is always whether these leaks provide so much insight the groups end up having to disband. In the case of Yanluowang, its site disappeared soon after the chat logs went public. Tologonov said the group probably won’t vanish, they will just get absorbed into other ransomware crews and keep doing what they’ve been doing.

“The group is not that big,” he said. “So even if they discontinue Yanluowang, their skills and their tools will be there, and they will probably just join other ransomware groups. This won’t be the end of them.”

Sean Powers and Will Jarvis contributed reporting to this story.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”