The Musicians Who Came In From the Cold

In 1985, Merryl Goldberg and three of her friends landed at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport on a rare trip behind the Iron Curtain. The visit was billed as a cultural exchange: four musicians from Boston touring the Soviet bloc.

But from the moment they landed, Goldberg said it was clear Soviet authorities had been expecting them. Men talking into their sleeves met them as soon as they got off the plane and asked them to bring their instruments and their bags over to an interrogation room to be searched.

The truth was, Goldberg and three other members of Boston’s Klezmer Conservatory Band, weren’t just four musicians from Boston. They were in the Soviet Union on a secret mission. With the help of an American non-profit called the Action for Soviet Jewry, they had been instructed to make contact with a group of musicians and dissidents who played in something called the Phantom Orchestra.

“They were called the Phantom Orchestra because they had to play somewhat in secret,” Goldberg told Click Here. “If they had gone out and decided, ‘Oh, we’re going to play in the park,’ they would have been picked up and arrested.”

That’s because the orchestra members weren’t just wayward musicians. They were dissidents. Most were refuseniks — people who asked the Soviet Union for permission to emigrate and were denied. Moscow considered them enemies of the state and just being found carrying their names and their addresses would have been a problem.

Which is why those moments in the airport were so tense.

“They started going through everything, and I mean, absolutely everything,” Goldberg said.

Everything, including their music.

“And I remember they're going page by page by page...”

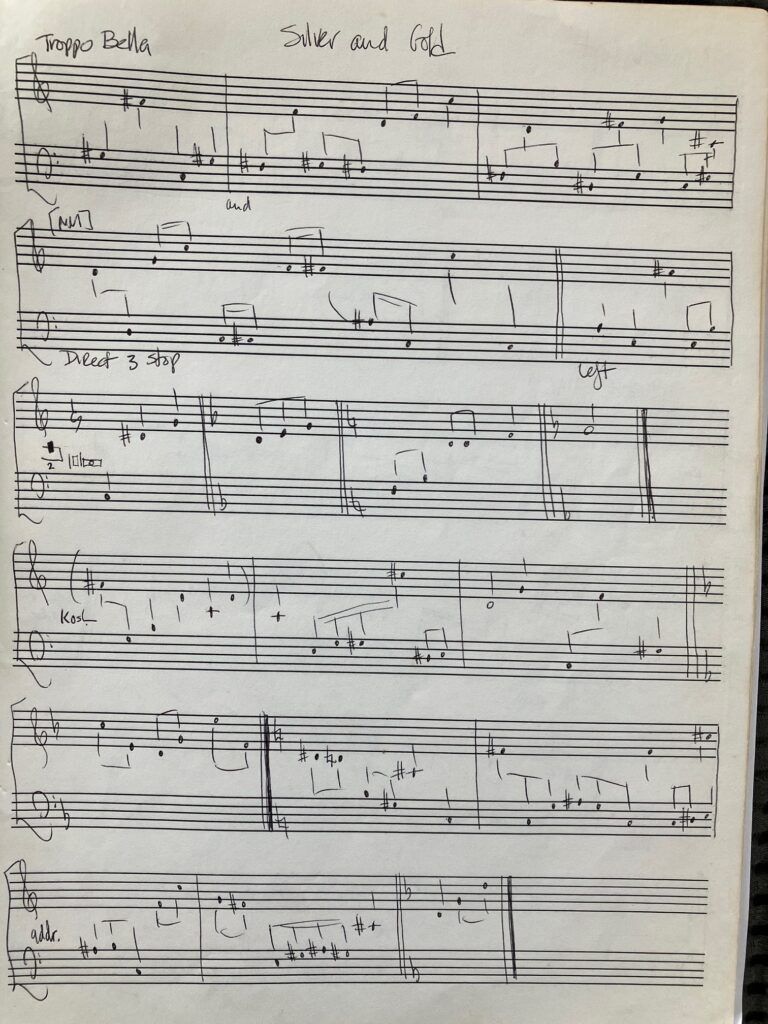

Had the custom officers known how to read music, they might have been surprised. The melodies made little sense — they would need to be played in a weird time, the notes didn’t flow so much as crash up against each other. Maybe it could pass as “modern music,” Goldberg said.

There was a reason for that: it wasn’t just music — it was code. And as Goldberg stood before a young Soviet officer at the airport who was studying her sheet music, she was sure the gig was up.

Coding Music

Using music to mask coded messages isn’t entirely new. Josephine Baker did it in World War II. She was a Paris celebrity, a singer and dancer and all around bon vivant in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. She was famous for walking her pet cheetah down the Champs-Élysées. She also happened to be a secret member of the French Resistance.

Baker would sing at parties, chat up important people and then pass along what she’d learned to the allies. She sent her dispatches out by writing messages in invisible ink between the notes in sheet music. Goldberg and her bandmates did something a little more complicated: they embedded the code in the music itself.

If you think back to your elementary school music classes, you learned about the staff — the five lines (E-G-B-D-F) and four spaces (F-A-C-E) that make up sheet music. That was the basis of Goldberg’s code. “But then you have the problem of 26 letters with only eight notes,” Goldberg said. “What I did without giving it away was I created a situation using chromatics.”

Chromatics are the twelve half-steps when you play the black and white keys on a piano. Goldberg said adding chromatics to the mix allowed her to “figure out all 26,” she said, with “three leftover ones like X, Y, Z, but you don't use X, Y, Z all that much.”

The result was a coded melody — Philip Glass without the genius. “If someone knew music and looked at it, they’d think, “Huh, that looks like modern music,” she said.

The contact and name of a dissident musician they were supposed to meet in Moscow sounded like this:

The man who helped organize the trip, Hankus Netsky, said the code’s creation story is in dispute. He remembers each member of the Soviet Union trip’s quartet creating their own version of the code. “The idea of having a musical code was fairly obvious, since it was something we all would be able to decode,” Netsky said. “And I say that as somebody who is very challenged to do mathematics in any respect.”

That said, he concedes that “Merryl’s was probably the most sophisticated because she's that kind of person.”

It looks like modern music, but the notes, chords and writing in the margins are actually coded messages. Buried in those musical notes is contact information that helped Goldberg and her friends meet with Soviet dissidents in 1985. (IMAGE: Merryl Goldberg)

Though memories differ, there is something that no one disputes: after Soviet officials went through page after page after page of Goldberg’s sheet music at the airport the day they landed; they returned it to her without a word. “It was just really fantastic,” Goldberg said.

Her code had worked. Now they had to find the Phantom Orchestra.

Old Fashioned Surveillance

Goldberg, Netsky and the two other Klezmer band members — Jeff Warschauer and Rosalie Gerut — had landed not just behind the Iron Curtain, but in the middle of a Cold War thriller with all its attendant set pieces.

Netsky remembers good-cop-bad-cop interrogations, people who followed them, even a hotel room that seemed to be bugged: “As we left our room, I remember Jeff saying, ‘It's too bad the sink is leaking,’” Netsky said. “And then when we got back from dinner, the sink was fixed.”

Some of the spycraft was almost comical because it was so cliche. “We would walk up the street and the last car on the block would flash its lights,” Netsky said. “And then we'd cross the street and the first car on the next block would flash its lights. And then the same thing would happen on the next block.”

They played the part of well-behaved tourists in Moscow, and eventually left for Tbilisi, Georgia, where the Phantom Orchestra was based.

IN 1985, FOUR MUSICIANS FROM BOSTON SLIPPED BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN TO MAKE CONTACT WITH A RAGTAG BAND OF DISSIDENT MUSICIANS KNOWN AS THE PHANTOM ORCHESTRA. MORE THAN 30 YEARS LATER, “PHANTOM WEST” WROTE A COVER DESCRIBING THE TRIP. (VIDEO COURTESY OF HANKUS NETSKY)

The Boston musicians were eager to make contact with four members of the orchestra: Isai and Grigory Goldstein, Jewish brothers who had been singled out by the Soviet regime because they wanted to move their family to Israel; and Eduard and Tengiz Gudava, two Catholic brothers who had been agitating for Georgian independence. They had been doctors and were stripped of their jobs and had spent some time in labor camps for their activism.

The first stop would be the Goldstein’s. They lived in a Soviet housing block in Tbilisi. There were no addresses on the buildings, so the Boston musicians wandered around for hours following the directions to the apartment they had encoded in their music.

Netsky was sure the Americans had lost their KGB handlers during the trip and said as much to his hosts. Grigory Goldstein laughed and looked out the window. He pointed to four cars. They were all KGB, he said, but he told Netsky not to worry: “They're pretty much always there.”

Goldberg remembers asking if they should leave. “Tell us if you want us to just turn around and go away,” she told them. “And they laughed at us. Like, of course you're being followed. And please come in because we need you to visit. We need you to tell our story.”

‘100% free’

There is a rare tape of the Phantom Orchestra playing. On it a young Avi Goldstein, the son of Isai, introduces the group and they play a set of Klezmer tunes and “Jingle Bells” and Buck Owens. But the one that resonated with the Americans was a standard: “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” — played with an eclectic ensemble of instruments — an upright piano, a couple of guitars, some timpani.

All these performances unfolded in the small Tbilisi apartment of the Gudava family. There was no concert hall or underground venue for the Phantom Orchestra; there was just a Soviet bloc apartment with some music stands, a piano and heart.

“The chairs went into the other room, I remember,” Netsky said. “And the idea was, ‘Hey look, we have visitors; they’re musicians.’ It’s time for the Phantom Orchestra to come meet and play a concert.”

The refuseniks were no strangers to dissent: Isai Goldstein had been speaking out since the early 1970s; his son, Avi, had been beaten up and called anti-Semitic names years earlier; Grigory had served time in a labor camp for “parasitism.”

When they brought in four Americans to play, members of the Phantom Orchestra were well aware of the risk. “They knew that there were people in the audience who were KGB,” Netsky said. “So in the middle of the concert, Isai Goldstein got up and gave a very defiant speech basically saying, ‘We are musicians. We are going to express ourselves any way that we want and we are going to be free.’”

The Phantom Orchestra and their western friends played a familiar playlist for the group. There was “Jingle Bells” and Jewish folk songs like “7:40.” The Gudavas sang and played guitar. Goldberg remembers a woman named Marina on the piano. They had a violin, Gregorian chants, more Russian folks tunes. No song meant more, though, than one about hope and escape.

“I think ‘Somewhere Over The Rainbow’ touched us in a way that I hadn't been touched before,” Goldberg said. “And I think because of the whole feeling of the song, and the hope in that.”

And for an evening, the Soviet minders and all the cloak and dagger — the coded directions, clandestine meetings — all faded away. The music took center stage.

“For the people there who had so much courage and were constantly battling whatever was gonna happen to them for their activism,” Goldberg said, “playing music was the time when in their brains they could be totally, 100% free.”

As they went back out into the night, they tried to recall the smallest details of what they had learned from their hosts — their family stories, the marriage announcements, the government repression — that they would later code into their music, so they could tell the world. And it went without saying that that night in Tbilisi their love of music had served an even greater purpose: they had completed its mission.

Only days later, the group again found itself before angry Soviet authorities. Their performance with the Phantom Orchestra, their meetings with dissidents, their role not just as cultural exchange musicians but as advocates for refuseniks.

What they didn’t know was how the four Bostonians expected to get all these stories out. It was in their music. At the airport, as they waited to be deported, the musicians stood before Soviet officials and watched as they tore apart their bags looking for messages or clues about their mission.

“I remember being surrounded by military, and they go through all of our stuff again, including our music again,” Goldberg said. As the customs officer scanned every page, he looked at Goldberg, then “handed it right back,” she said.

The broken melodies had hidden their Soviet friends’ stories in plain sight.

“And I think that’s part of what the goal of many of the folks was, you know, if your story is never told, it’s like it hasn’t happened,” Goldberg said. “So it was really important to get stories out there. It means you exist, and other people know you exist.”

The group returned to the U.S. with stories about dissidents and refuseniks no one had ever heard. It sparked speeches and Congressional hearings, and new calls to help refuseniks wanting to emigrate from the Soviet Union. Not long after, the Goldsteins were allowed to emigrate to Israel.

The authorities took aim at the Gudava brothers. They were jailed after the concert for what the Kremlin called treasonous activities and were finally released in April 1987, on the condition they would leave the Soviet Union for good. They landed in Boston a few months later.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”

Will Jarvis

is a podcast producer for the Click Here podcast. Before joining Recorded Future News, he produced podcasts and worked on national news magazines at National Public Radio, including Weekend Edition, All Things Considered, The National Conversation and Pop Culture Happy Hour. His work has also been published in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Ad Age and ESPN.