The future of the internet is up for vote at the U.N.

Europe is this week hosting a contest for world power, but one that few people are aware of. Hundreds of miles south of Ukraine delegates from every country recognized by the United Nations are gathering in the Romanian capital of Bucharest. They will on Thursday elect five officials who will head an obscure U.N. agency called the International Telecommunications Union. Ultimately, their votes will decide the direction for internet governance, whether it is principally controlled by states or by stakeholders.

The delegates’ options for the top position, the new Secretary-General, are an American and a Russian. Given the war to the north of the ITU Plenipotentiary Conference, one might be forgiven for assuming a result against the Russian candidate is a foregone conclusion. But that is not the belief of onlookers in Washington, D.C. and London for whom the ITU has over the past decade become one of the most vigorously contested parts of the international system.

It wasn’t always so. When the ITU began in 1865 it had a simple function: to make sure that the telegraph systems across Europe were interoperable. Its remit has since expanded to include many other forms of technology. Now it is responsible for addressing a range of challenges posed by cross-border telecommunications, from the use of the radio spectrum, to satellite orbits, and even fiber-optic cable standards.

All of these could easily stop working without some harmonization between nations, but aside from the technical arrangements there are cultural challenges posed by cross-border communications. States that want to restrict the information their populations can access — because, for instance, foreign media or activist expatriates are deemed to be undermining the legitimacy of the government — see their “information sovereignty” as a fundamentally cross-border issue, one which should be addressed at the U.N. level.

Russia and China have been among the most vocal states offering this view, attempting at the General Assembly to expand the definition of "cyber crime" for the purposes of international treaties to include anything that an individual member state considers to be illegal online. To these ends, both countries have also attempted to introduce the phrase “information security” instead of “cyber security” in official documents as the latter could be interpreted in a way that endorses their efforts to control internet content. The U.S. and U.K. have repeatedly attempted to resist this framing, including by refusing to sign an ITU treaty in 2012 which they complained politicized the agency as a neutral standards body.

As an agency the ITU accepts new standards (often proposed by the private sector, from which it has roughly 900 members) on a consensus basis. There is no voting other than at the four-year plenipotentiary conferences when officials are elected by a relative majority through a secret ballot, with each member state getting one vote. According to multiple sources with either direct knowledge of campaigning for these votes, or who have been briefed on the efforts, these election campaigns are becoming very large and very competitive operations.

"I don't think 20 years ago, the U.S. would have put up a candidate,” Emily Taylor, an associate fellow with Chatham House, told The Record.

“Maybe they would, but there used to be an attitude — certainly from the technical communities that I've spent most of my career with in the ICANN [Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers] environment — of ‘don't engage with the ITU because it will embolden them and then they'll think they've got some role in the internet.’ That speaks to a lot of the reasons why our democracies have not wanted to define the way that a global communications technology is governed.”

But this vacuum of activity from democracies, who are now “in fact in the minority,” she pointed out, meant others were given the room to engage without the drag effects of democratic values.

Bruised Britain

During the last plenipotentiary, back in 2018, the U.K. was trying to re-elect Malcolm Johnson as the Deputy Secretary-General of the ITU. He was seen as a valuable counterbalance to the Chinese Secretary-General, Houlin Zhao, who was running unopposed. But his re-election was far from guaranteed, according to multiple sources who spoke to The Record on the condition of anonymity to discuss the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s campaign.

At the time staff at the FCO were demoralized. For the previous two years Boris Johnson had been Foreign Secretary — a role he was awarded in the wake of the U.K.’s surprising vote to leave the European Union — and civil servants told The Record that he was not considered an especially hard worker. He would eventually resign a few months before the plenipotentiary in a bid to bring down Theresa May’s government. Despite his charisma and personality, which sources told The Record were generally enjoyed by staff and foreign dignitaries, under his leadership the FCO had been humiliated by defeats in a series of elections for international bodies, including the World Health Organization and the International Court of Justice. There was a growing fear that Britain’s reputation and role in the world was becoming diminished.

To nip the losing habit in the bud, the re-election of Malcolm Johnson was made a priority across Whitehall, with both the Foreign Office and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) having a stake in the matter. But his rival from Burkina Faso was expected to win the votes of the bloc opposing Britain and was endorsed by the African Union, whose own bloc-like vote had directly contributed to the U.K.'s defeat in the WHO election the year prior.

Great to see such good turnout at the hosted lunch @ITU #Plenipot today. Speeches by Malcolm Johnson @ITU_DSG and Houlin Zhao @ITU Secretary General confirmed the valuable cooperation between #UK and ITU pic.twitter.com/ujCuG27wIM

— Lord (Tariq)Ahmad of Wimbledon (@tariqahmadbt) October 31, 2018

The campaign was led by Julian Braithwaite at the Foreign Office, a longstanding diplomat described by The Record’s sources as being from “one of the Foreign Office families” – both his father Sir Roderick Braithwaite and his mother Jill Braithwaite had served in the diplomatic corps – prompting the nickname “Julian Birthright” among some of his less generous colleagues.

Sources said Braithwaite’s campaign was “fun to work on” — there were dozens of meetings and a fancy but not lavish reception was put on for the other delegates in Dubai with plenty of handshakes and expensive hampers (for American readers, those are posh gift baskets — not laundry bins).

Some of the most audacious plans to mobilize the vote for Johnson never came to fruition. It was even proposed that the Foreign Office fund trips for Pacific Island delegations who were unable to afford attending – Kiribati being regarded as a regular absentee – so that they could vote in the U.K.’s favor. This was ultimately scuppered by the realization that the FCO would have to pay for the delegations to attend the entire weeks-long plenipotentiary, including their hotel stays.

Ahead of the vote itself, the Foreign Office believed it had secured pledges from 152 countries to support Malcolm Johnson. Of these pledges 106 were given in writing and 46 verbally. The team toasted wins, believing they had flipped Rwanda. In the end dozens of the delegations who had given the U.K. their pledges were lying. The secret ballot will forever conceal whom. Despite the 152 pledges, the U.K. received only 113 votes. Fortunately, with 178 member states present, it was enough for Malcolm Johnson to be re-elected. There were celebrations into the evening.

Spokespeople from the Foreign Office and DCMS did not dispute the details of the 2018 campaign but declined to contribute any additional comments.

"For the U.K.'s on-the-record position on the ITU elections we'd point you to U.K. ambassador to Geneva Simon Manley's comments given to the Inside Geneva podcast last week," a DCMS spokesperson added.

Manley told the podcast: “We've been clear right across the U.N. system that this is not the right moment to see Russians elected to top positions, when Putin's regime is flouting international law and flouting the charter.”

He explained that the internet could only remain “open, peaceful, secure” if it retained the “multi-stakeholder approach in which you are bringing people together – business, governments, experts, regulators – rather than a top-down restrictive approach to setting rules, which is all about setting rules that restrict access to the internet.

Anxious America

The campaign for the American candidate, Doreen Bogdan-Martin, is being led by Ambassador Erica Barks-Ruggles who stressed to the House of Representatives last year how vital the fight for the ITU was to counter Russian and Chinese efforts to reshape international institutions in their own favor.

Nathaniel Fick, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for Cyber, is making his first official overseas visit to Bucharest to support Bogdan-Martin, who has also unusually received a string of high-profile endorsements – including from President Joe Biden – which come with a degree of political risk if she loses.

Although nobody with knowledge of the American campaign wanted to publicly express their doubts for The Record, the consensus was that there is significant anxiety about the election.

My first trip as Ambassador at Large is to Bucharest for the 2022 @ITU Plenipotentiary Conference, a key opportunity to engage foreign counterparts and support @DoreenBogdan’s candidacy for ITU Secretary-General. -NF pic.twitter.com/swVazn71iH

— Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy (@StateCDP) September 27, 2022

Bogdan-Martin isn’t a controversial candidate. She is “a known quantity, a deeply-respected career ITU person,” said Emily Taylor, who noted that she “has been incredibly effective in the development sector,” which is expected to buoy her chances. Bogdan-Martin has spent 28 years at the agency in various capacities, including most recently at its Development Bureau. She would be the first woman to head the agency in its 157-year history.

The Russian candidate, Rashid Ismailov, doesn’t have quite the same résumé. He has experience in the telecommunications sector, including having worked as Russia’s deputy minister for telecoms and mass communications, and has also occupied senior roles in Russia for three of the world’s largest telecommunications businesses, Ericsson, Nokia, and Huawei.

Both of the candidates' campaign brochures are purposefully anodyne, full of the usual U.N. talking points about development and collaboration. The differences about internet governance and regulation are as subtle as they are important. Perhaps the invasion of Ukraine will play against Ismailov, but the general trend suggests that the fight to keep the ITU focused on standards rather than governance is getting increasingly difficult.

Ismailov’s pre-election plans were inconvenienced last week when the Romanian Embassy in Moscow withdrew 14 visas that had been issued to members of the Russian delegation, describing the individuals as “a threat to national security.”

More than half of the Russian delegation is still able to attend and will be engaging in the normal pre-election events, including a reception. The move may have been a very small embarrassment and inconvenience for Russia, but was not expected to severely influence the vote.

But a furious statement in response by Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova could prove more damaging. She alleged the move was part of a Washington-led conspiracy, undoing the purposeful blandness of Ismailov’s campaign brochure. She explicitly accused the American candidate of being prepared to “push Western installations in the ITU to the detriment of users of the rest of the world” – implicitly suggesting that the Russian government viewed the role of Secretary-General as one of significant political influence.

Rising Russia

Back in December 2012 the ITU held what was known as the World Conference on International Telecommunications. It was the first treaty-level conference the agency had held since 1988, years before the web had even been invented. The idea was that the ITU needed to be dramatically modernized, but the conference featured what many saw as a major territory grab which would put internet governance into the hands of governments through the U.N. instead of keeping it with stakeholders such as ICANN, who were already filling that function.

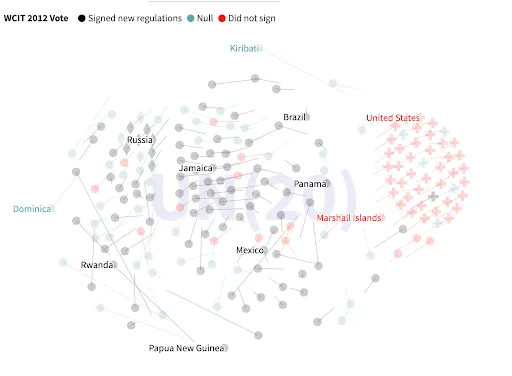

The eventual vote revealed a stark international division, with 89 countries – including Russia, China, and Iran – signing the proposed regulations, while 55, including the U.S., India, and most of Europe, refused to do so. There was a significant middle-ground that did not vote. Those who did not sign the 2012 rules are still bound by the ones they signed in 1988.

As detailed by Robert Collett, a former British diplomat and associate fellow at Chatham House, there have been five similar votes since then, and they show a soft but certain trend in voting patterns. The trend, he found, is in Russia’s favor.

"There is only so much one can read into a single vote,” Collett said. “Countries interpret the resolutions being voted on in different ways; they can connect votes to deals in unrelated policy areas; and unpredictable factors can come into play, such as someone missing a vote or misunderstanding their instructions,” he said.

However, Collett has put together insightful network diagrams, which reveal how a large cluster of middle-ground nations are moving closer to Russia and further from the U.S., reflecting “the fact that Russia has been proposing resolutions that gain majority support from the middle ground.”

At least for the West there is still a large middle-ground cluster for diplomats to focus on. Collet said this shows “a lot of countries are attracted to elements of the two very different visions for the future of cyberspace put forward by the U.S. and Russia”. The U.S. and Russia would both “like the middle-ground countries to choose one vision or the other, but past votes point to a reluctance to commit.”

The good news is that the binary nature of Thursday’s vote will force these countries to commit one way or another. The bad news might be which way they commit.

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and is also a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative.