The Entrepreneur and the Jihadist

The drone that would end Junaid Hussain’s short life in 2015 was the result of a series of avoidable events. Hacks that went too far. Hubris about not getting caught. Radicalization in prison and the targeting of a serial entrepreneur named Chris Ueland who, about ten years ago, found himself on the receiving end of one of Hussain’s hacks.

“We got this very, very weird live chat that we thought was fake,” Ueland said. “At first all we saw was that a gentleman with a weird name – [email protected] – and he was saying that, you know, he was going to hack us.”

It was 2012 and Ueland was running a content delivery provider called MaxCDN. The company was small, based in Los Angeles, and helped businesses load their content locally so their websites would run faster. It wasn’t the kind of high-visibility company that hackers would target for big money or prestige.

Even so, early one morning Ueland and his team found themselves staring at a computer screen as this guy named TriCk launched threatening lobs from cyberspace.

VISITOR: TeaMp0isoN Was Here all your servers are belong to us - TriCk

“He was asking for access to specific clients to presumably infect their delivery with some kind of malware,” Ueland recalled. “And we wouldn’t give it to him. So it escalated from there and then he asked for a ransom, $1,337 in Bitcoin.”

VISITOR: How did you get 0wned so bad?

VISITOR: I want $1337

VISITOR: please

VISITOR: hello?

Ueland was looking over the shoulder of his sales rep as chat unfurled.

VISITOR: bitcoins would be ideal

JUSTIN: anything else?

VISITOR: nope

VISITOR: u sent it yet?

Ueland remembers one thought kept “looping through my head: We’re going to go out of business.”

This is the first time Ueland is telling this story publicly and it is a tale about a small California startup, a world renowned hacker, and the series of unlikely events that brought them together. Even ten years later, Ueland still wonders, “Holy cow, how did we get in the middle of this?”

Hacking with purpose

In June of 2011 — almost a year before the hack at MaxCDN — a 17-year-old from Birmingham, England had burst on the British political scene. His name was Junaid Hussain, and he and his friends had managed to break into an email account that belonged to a staffer for former Prime Minister Tony Blair.

Hussain moved around the account and found the staffer’s copy of Blair’s address book, which he thought would be funny to publish. So he set up a website and provided the names, phone numbers and identifying information on a bunch of people in Blair’s inner circle.

Blair didn’t find it so amusing — calling it “despicable” at the time.

But the act managed to put Hussain and his hacker friends on the map. Suddenly everyone knew the name of his crew: they called themselves TeaMp0isoN.

According to an interview he gave to the website Softpedia around the same time, Hussain began joining online hacking forums and started learning about hacking when someone broke into a gaming account he had. “I wanted revenge, so I started Googling around on how to hack,” he told the Softpedia reporter, and eventually, as his skills developed, he started to use them.

“They would call me and say, we're going to do this,” said Lorraine Murphy, a journalist and hacktivist who befriended Hussain and the group. “And they’d say, ‘do you want to interview us? It'll happen on this day, you can interview us an hour later or whatever.’”

As Murphy remembers it, the guys on TeaMp0isoN thought the hack on the Blair staffer and the release of his address book to the public were hilarious. “They were just saying, this is so funny. You are going to love this when it hits.”

Murphy and Hussain had met years earlier on Twitter. “He was very much involved in Anonymous activities, and I had been writing about Anonymous since about 2006. And we just got chatting and you know how some people you just click with? I just clicked with him.”

She said he seemed like a nice guy – a sweet guy – and he was sensitive and empathetic. He used to send her rap music if she seemed down.

“He felt the pain of entire groups,” she said, and that seemed to motivate a lot of the hacks TeaMp0isoN would eventually launch. “They had a philosophical basis for all of this; TeaMp0isoN really did think that the government needed to be taken down a peg. They needed to be taught to respect the privacy of the people. So although they were trolls… It still had a moral imperative.”

Murphy said it had a kind of ‘Power to the People’ vibe. They didn’t want to break into servers for money or revenge. As they saw it, they hacked with a nobler purpose. TriCk genuinely believed that all this hacking could draw attention to things that needed to change in the UK, she said.

“The people shouldn't fear the government, the government should fear the people kind of thing, that’s where they were coming from,” Murphy explained.

Former Prime Minister Tony Blair and the people who found themselves on the other end of TeaMp0isoN’s hacks clearly saw it differently. Between 2010 and 2013, the TeaMp0isoN crew claimed to have broken into more than 1,400 different servers and websites and their victims – just to name a few – allegedly included Mark Zuckerberg, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, BlackBerry and, in April 2012, Scotland Yard’s counter-terrorism hotline. In that case, they bombarded the switchboard with hundreds of automated calls until it crashed.

Not long after the attack, Junaid Hussain gave an interview to the Telegraph newspaper and said that he’d hacked the hotline because, in his opinion, terrorism was something authorities fabricated to demonize Islam.

‘how about i make u a deal?’

Against that backdrop, the hack on MaxCDN seemed almost pedestrian, though not to people like Ueland and Justin Dorfman, who was on duty when TriCk appeared in the company’s help desk chat. Dorfman was one of the more senior support people. “And we were just like being very careful with what we said, because he was very trigger happy and very immature,” he said.

When TriCk wrote “this is TriCk from TeaMp0isoN,” it meant nothing to Dorfman. He just kept the guy talking – like a hostage negotiator in the movies trying to talk the kidnapper down.

“Honestly, that's how I kind of did it because I knew if we came back at him hard, it was going to backfire on us,” he said, so he just kept trying to de-escalate.

“I was like, okay, obviously this guy knows what he's doing so I didn't really care who it was because…he already proved himself,” Dorfman said. It was only after the fact that he thought to himself, “Wow. I mean, we're in the same league as Facebook – Facebook got hacked by this guy.”

Then, according to the chat logs, TriCk suggested that Dorfman just give him access to some of MaxCDN’s clients. If they did that, then he could forget the ransom. He was particularly interested in something called Stack Overflow. It’s an online reference for computer programmers, and programmers use it constantly. Dorfman said he figured TeaMp0isoN would want it for bragging rights. “If TeaMp0isoN pwned and owned Stack Overflow then, you know, in their eyes that’s a feather in his cap.”

VISITOR: how about i make u a deal?

VISITOR: u give me access to BackTrack, ExploitDB and Stack Over

VISITOR: and I won’t touch ur site

VISITOR: theyl never know it was u

Naturally, Dorfman said no. He wasn’t just standing on principle (although there was that, too). The truth was MaxCDN didn’t actually host Stack Overflow on its servers, it just proxied some of its static content.

Crowing about hacks

Looking back on it, Ueland said there was one other thing about this that was weird – this guy TriCk kept mentioning Syria. “And Syria, wasn't really in the consciousness of things at that time,” Ueland said. “So it felt like some kid pretending to be Syrian, pretending to be with the Syrian Electronic army.”

The Syrian Electronic Army was a group of computer hackers that supported the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. They first surfaced in 2011. The connection would become important later.

Ueland and his team reacted like anyone would after a hack. They started moving to protect their clients – and they called in the FBI, something Ueland said he’d never done before. The agents showed up two days later. They met outside the office at an Italian restaurant in Studio City, CA, called Miceli’s. The agents had suggested it.

“It’s actually a really cool place with singing waiters and waitresses and it’s kind of comfort Italian food.It’s like a Hollywood icon,” Ueland said, adding that there was no singing at the lunch. Instead, he found himself sitting across from two agents who were telling him they were unlikely to find or punish whoever had hacked into MaxCDN’s systems.

Then, a couple of months later, the FBI called out of the blue. They said they were working with the London Metropolitan Police on a case that seemed to involve their hacker. They wanted the dossier that MaxCDN had put together after the attack. “And we were just like, holy cow, how did we wind up in the middle of all this?” Ueland said.

By 2012, TriCk and TeaMp0isoN had taken credit for launching more than a thousand hacks; and this wasn’t something they did quietly – they crowed about it. They set up a webpage with a list of all their alleged victims and they kept adding to it, taunting authorities and daring them to bring them in. The group appeared so untouchable, even the people who were on the receiving end of their hacks hesitated to help.

“We were very reluctant to help the London police with the actual court case because of fear of retribution,” Ueland said. “Honestly I pictured these just as kids and as annoying. Then I realized it was dangerous for the business. In the past, we might have had a customer that got defaced and we would replace the website within an hour. Now it's like my customers are at risk and there's nothing I can really do about it.”

Ueland gave the FBI permission to share the dossier on TriCk. “We had detailed logs and detailed information on how he had gotten in and his IP addresses,” Ueland said. “And the whole package that we had put together for the FBI was enough to kind of pin [the MaxCDN hack] on him directly.”

The U.K. judge who heard the case sentenced him to six months in prison.

“It was the biggest thing that I had worked on with law enforcement up until that point, I would assume it was pretty big for them as well,” Ueland said. “It was this kind of a situation where we could do nothing about it, that turned into something that helped kind of the world.”

But the story doesn’t end there – either for Ueland or for TriCk. Ueland said he was so changed by the experience he began starting cyber security companies. (Full disclosure: one of those companies, Security Trails, was purchased by Recorded Future late last year. The Record is owned by Recorded Future.)

“I was like all-in drinking the Kool-Aid on security after this,” Ueland said.

The CyberCaliphate

TriCk, for his part, headed in a very different direction.

Lorraine Murphy had spoken to him shortly before his arrest and she remembered saying that he didn’t think Britain could be saved.

“He was in a very dark place,” she said. “And that had been going on for a few weeks. I mean, when you get arrested, you normally know you're going to get arrested. You see the police following you. They’re questioning your friends. You can see the noose tightening, and I think that's what was happening with him.”

Murphy said he never felt that all the cracking into systems he was doing was wrong. “I think he felt when he was arrested that it was the system smacking him across the face for doing the right thing,” she said.

He spent four months in prison and emerged, Murphy and others say, a totally different guy. He had moved from an anarchist position to more of an organized and fundamentalist one. Something that is not terribly unusual in prison, radicalization happens a lot. Though Murphy said to have that happen in four months “is pretty shocking.”

In hindsight, it’s clear that the hacks Hussain dreamed up had a real political bent. He worked on Operation Free Palestine, a scheme targeting Israeli credit cards; he named and shamed members of the far-right English Defense League and TeaMp0isoN claims to have hacked NATO and the British Ministry of Defense. Murphy says they attack institutions they thought needed to change.

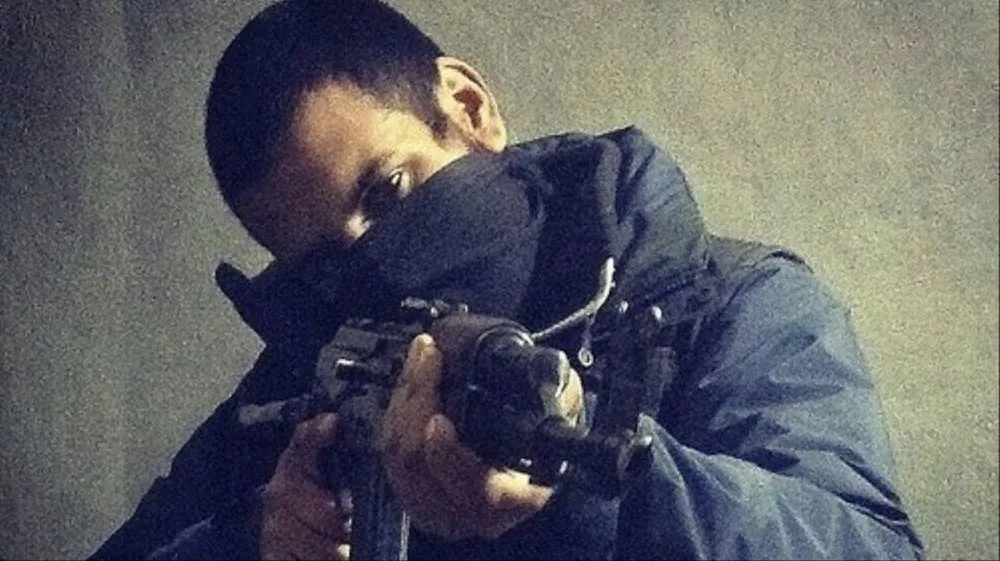

Not long after Hussain’s release from prison he popped up in Syria. He had joined ISIS there and in a short time became their number one hacker – a leading member of ISIS’s so-called CyberCaliphate.

Among other things, he broke into the U.S. Central Command’s Twitter and YouTube accounts and posted soldiers’ addresses and contacts. He started using new techniques to recruit foreigners into the group and with his help, ISIS began using the web to spread their message and launch attacks…

They began to use encrypted apps, social media, and online magazines and videos in new ways. Despite all the hacks and the bravado that marked his teenage years, it seems most people remember more about the way TriCk died than what he did when he was alive. He was killed by an American drone strike just outside Raqqa, Syria in August 2015.

Ueland doesn’t remember exactly where he was when news of TriCk’s death filtered out. Someone sent him a link to a news story. “I remember feeling, Holy Cow, how did this happen,” he told me.

Murphy heard about it where she got a lot of her information: on Twitter. “I was very sad,” she said. “I was shocked because when you’re dead, there's no possibility of redemption. I always thought he’d get tired of all of that and eventually he'll realize that he's doing harm and we can get him back. And we never did. We never got that chance.”

Sean Powers and Will Jarvis contributed to this story.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”