Suspected Chinese state-linked threat actors infiltrated major Afghan telecom provider

Four distinct infiltrations by suspected Chinese-state sponsored threat actors stole gigabytes of data from the corporate mail server of major Afghan telecom provider Roshan within the past year, with data exfiltration by some spiking during the Taliban’s recapture of the country, according to new research from Recorded Future’s Insikt Group.

The attacks highlight China’s intelligence interest in the region as the Afghan people face radical changes to their physical and digital lives after U.S. troops withdrew following a two-decade occupation and the Taliban regained control of the country.

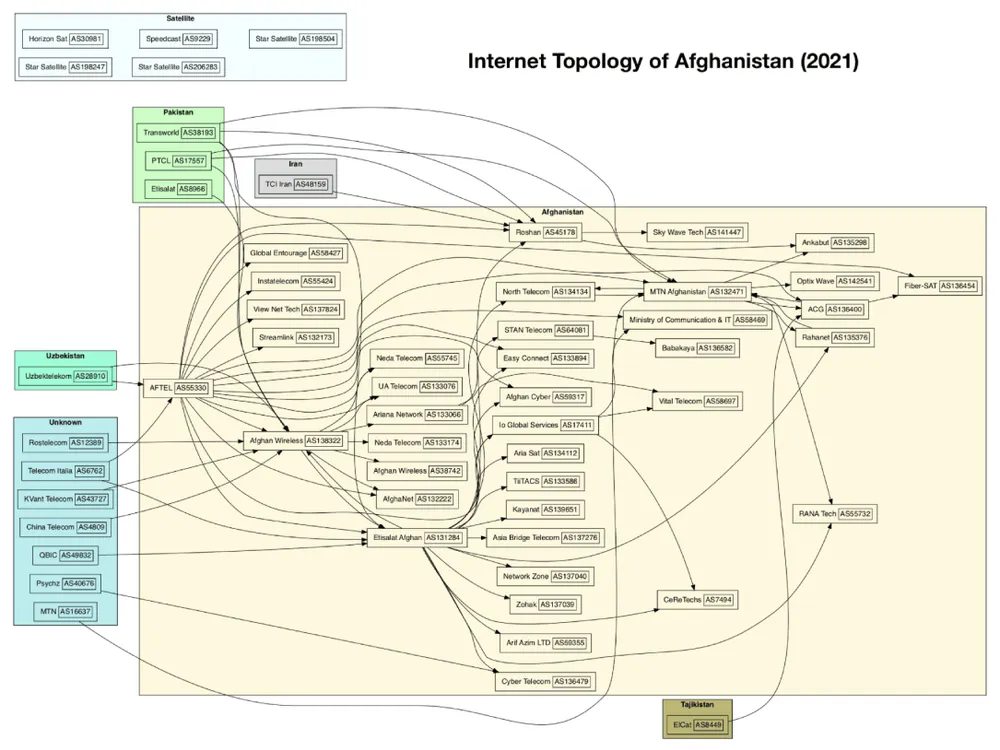

Roshan is a mobile phone provider that operates throughout Afghanistan, “covering all 34 provinces with over 6.5 million active subscribers,” according to its website.

“It’s among the biggest suppliers of Internet access to the people of Afghanistan” and a major source of online traffic in and out of the country, Doug Madory, Director of Internet Analysis at Kentik and a longtime observer of global traffic trends, told The Record.

“Telcos are the gateways through which all information flows into the country,” explained Raman Jit Singh Chima, the Asia Policy Director at digital human rights group Access Now. Roshan in particular, he added, has been an important lifeline in the country in recent weeks because it’s among the most stable local telecom providers.

The researchers identified the apparent infiltrations of Roshan’s internal mail server through an analysis of adversary instructure and global network traffic, including observation of communication from the infected system to command and control servers.

Recorded Future notified Roshan of the compromises before Insikt Group’s public disclosure of the attacks. The Chinese Government and Roshan did not respond to requests for comment before publication.

In a statement emailed after publication, a Chinese Embassy spokesperson described tracing the origin of cyber attacks as a "complex technical problem."

"Linking cyber attacks directly to one certain government is a highly sensitive political issue. China hopes that relevant parties will adopt a professional and responsible attitude," the statement said. "Qualitativing[sic] cyber incidents must be based on sufficient evidence instead of groundless speculation," the spokesperson wrote.

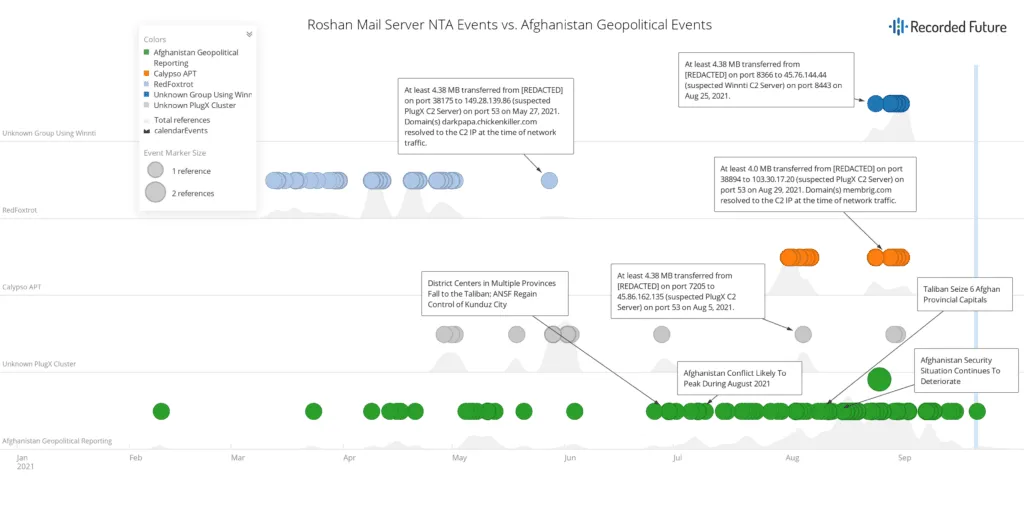

The earliest activity identified by the researchers that targeted Roshan was linked to suspected Chinese state-sponsored group Calypso Advanced Persistent Threat (APT). That intrusion appears to date back to at least July of 2020 and was ongoing through September 2021, with a significant increase in activity in August and September of this year.

The researchers identified the same Roshan mail server communicating with the infrastructure of another named suspected Chinese APT group, RedFoxtrot, from at least March through May of this year.

RedFoxtrot also appeared to have infiltrated another unidentified Afghan telecom provider during this period, according to the Insikt post published Tuesday. A report from the research team publicly released in June previously identified RedFoxtrot as targeting unnamed telecommunications companies in Afghanistan as well as India, Pakistan, and Kazakhstan. The report also linked the RedFoxtrot to a specific unit of the People’s Liberation Army, Unit 69010 located in Ürümqi, Xinjiang.

As part of the latest release, the Insikt researchers also reported two other infiltrations of Roshan's mail server using tools and methods associated with suspected Chinese-state sponsored attacks, but not attached to a specifically named APT. One involved a PlugX cluster and the other involved a Winnti cluster, the latter of which saw increased exfiltration activity during the regime change.

Recorded Future observed at least 4GB of data exfiltration across the four infiltrations, although the true figure may be much higher, according to Jon Condra, Insikt Group’s Director of Strategic and Persistent Threats.

The exact content of the stolen data is unclear. However, access to Roshan’s internal company emails might give attackers insight into issues of technical and geopolitical interest to China, according to Chima.

For example, corporate emails of a telecom provider may contain information about intercept requests from local authorities that could provide insight into investigations or details about the physical and digital security measures protecting telecom infrastructure that could make it easier to compromise such systems, he said.

Attackers often leverage access to one system on a network to infiltrate others, although it’s also not clear from the latest research how the Roshan server was infected. Insikt researchers don’t have visibility into how the server was compromised, but Chinese APT attacks often begin by exploiting external-facing services or spearfishing campaigns, according to Condra.

“While we cannot confirm at this time, it is possible that the Roshan mail server was accessed via lateral movement from other compromised devices in the Roshan network,” he added.

Access to telecom infrastructure can be a major intelligence source.

“The targeting of telecommunications firms offers a hugely valuable platform for strategic intelligence collection, be it for monitoring of downstream targets, bulk collection of communication data, as well as the ability to track and monitor individual targets,” the Insikt report noted.

Governments around the world, including the U.S., have long targeted telecommunications or networking infrastructure as part of intelligence operations. In fact, WikiLeaks claimed in 2014 that Afghanistan was among several countries identified as being subject to telephone mass call interception and recording by the U.S. in documents shared with journalists by Edward Snowden.

Documents from Snowden also revealed efforts by the U.S. government to tap into undersea cables that are a key part of global Internet infrastructure and how U.K. spies hacked into a Belgian telecom firm.

China has also been accused of targeting telecom infrastructure. In 2019, security firm Cybereason described a years-long cyber espionage campaign by a suspected Chinese government-backed threat actor targeting telecom providers. The campaign reportedly targeted at least 10 unnamed cellular providers in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe—with the attackers using lateral moves to penetrate systems and accessing call record metadata in one case study.

Another Cybereason report released this August linked “intrusions detected targeting the telecommunications industry across Southeast Asia” to suspected Chinese threat actors.

China has a significant intelligence interest in Afghanistan due to shared borders and because it figures into the country’s “Belt and Road” initiative, a strategy announced in 2013 that aims to build economic and diplomatic relationships along regions connected to the historical “Silk Road” trade routes through infrastructure and other investments. However, this soft power strategy is complicated in some areas by China’s repression of its Muslim Uighur minority—whose treatment has been enabled, in part, by extensive digital surveillance and censorship.

The news of the infiltrations also put a spotlight on the complex digital security landscape facing many in Afghanistan.

Afghans who worked with the U.S. and its allies have rushed to wipe their digital trails, but many remain worried about caches of sensitive information, including a U.S.-built biometric database tracking Afghan military personnel and the vast amount of historical communications information held by local telecom companies, may be used by the Taliban regime to identify them.

Some international digital rights groups, including Access Now, have provided security guidance for Afghans and urged local telecom providers to take security measures to prevent their records from being used to enable human rights violations.

When the Taliban was in control of Afghanistan in the 1990s, it banned the Internet. But in the decades since, the group aggressively used social media and other online tools for recruiting—and its long-term strategy for online access in the country remains unclear.

Madory says there have been minor services disruptions in the country since the Taliban took over, but he hasn’t seen data indicating attempts to shut down national online access.

“Observing global traffic, it’s like almost nothing has happened,” he told The Record.

This story has been updated to include comment from the Chinese Embassy.

Andrea Peterson

(they/them) is a longtime cybersecurity journalist who cut their teeth covering technology policy at ThinkProgress (RIP) and The Washington Post before doing deep-dive public records investigations at the Project on Government Oversight and American Oversight.