Spyware and ‘a world of Bond villains’

Late last month, a group of researchers at the Citizen Lab published a groundbreaking report that alleged 65 people from Catalan independence movement had been targeted by the world’s most advanced spyware. Just a few weeks later, Spain announced that cell phones used by the prime minister and defense minister had also been infected by spyware. It was just the latest example of the growing normalization of hack-for-hire software, wielded not just among autocrats and despots but by democratic nations, too.

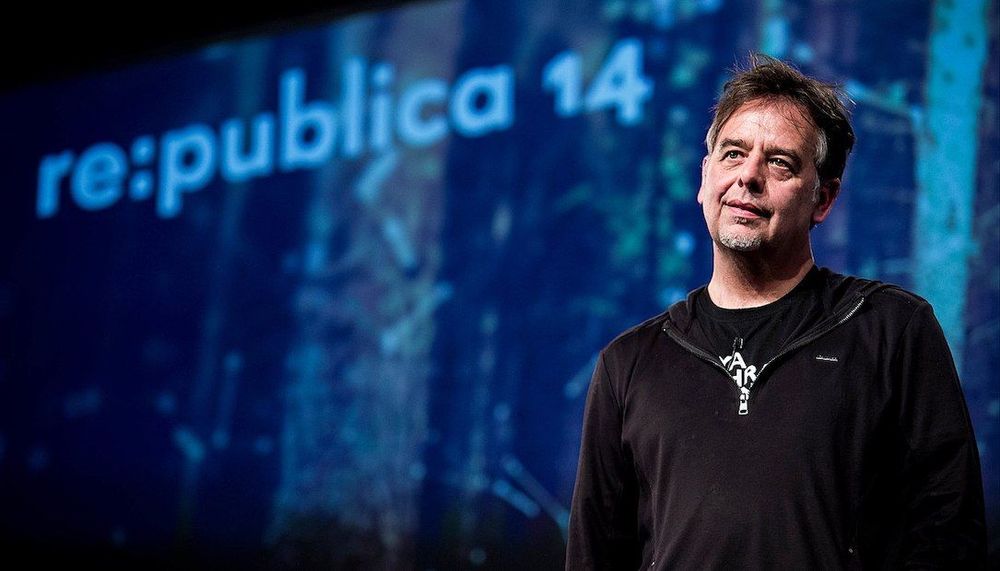

For more than two decades, the Citizen Lab, housed at the University of Toronto, has been uncovering high-tech human rights abuses from early hacks on the Dalai Lama to today’s spyware on cell phones to methods of cyber espionage pulled right from the pages of a John le Carré novel.

In an interview with Click Here, Ron Deibert, the director of The Citizen Lab, explains the growing threat, how we got here, and what democratic governments need to do to stop it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Click Here: So how did we get here?

Ron Deibert: Well, if you start with the broadest underlying factor among them, I think it has something to do with globalization and, in particular, privatization and deregulation. If you go back to the Reagan-Thatcher era, back in the sands of time in the late 1970s, 1980s, this wave of privatization brought about — not intentionally, perhaps — vast inequalities of wealth. So now you have a situation where you have a class of billionaire oligarchs.

Then more directly is what I would call the rise of privatized subversion: people who used to work for intelligence agencies for the state taking advantage of new opportunities. Many of them created lucrative startups, and governments themselves started contracting out more to private companies to do things that typically used to be in the control of the state. A good example of this is Israel. You have this very explicit startup culture; people who have an intelligence background — maybe they go through their military service — are encouraged to develop businesses and market their techniques and skills to both government clients and private-sector clients. [It’s] often law firms, front companies, private equity firms, you know, anyone that's involved in the kind of malfeasance that surrounds kleptocrats and billionaire oligarchs. And they often go by benign-sounding names like “reputation management” or “deep background checks.”

And there are so many other companies; it’s not just NSO Group [an Israeli company company that makes surveillance software that can be remotely implanted in smartphones]. A sister company to NSO Group called Circles exploits a particular insecurity in the global mobile cellular system. So there's a rather obscure technical protocol called “SS7” that was set up back in the 1970s to handle roaming and billing issues. As people started taking their mobile phones from North America to Europe, there needed to be a way for the telecommunications companies to handle billing.

That protocol was designed almost completely without security. So companies have realized it's really quite ingenious that — if they can get what's called a global title, effectively a license to operate in the telecommunications club through registration in, let's say, Bulgaria or the Channel Islands or Cyprus — they can enter into that club and access that protocol, which gives them the ability to locate any mobile phone, anywhere in the world. And, in some cases, intercept text messages and voice calls. It was, by the way, this type of service provided by a company called Rayzone that the Sheik of Dubai used to locate the cell phone of the ship captain on whose yacht his daughter was escaping from the United Arab Emirates.

CH: Has this been going for quite some time and we didn’t notice, or is it new?

RD: I think it's both. In a way it's been going on for longer than I think a lot of people realize, but it is a relatively new thing. However, I think now it's certainly becoming more apparent to a lot of policymakers. So I'll give you an example from one of our own research reports. Back in 2017, we were contacted by Ethiopians who were expats in the U.S. working for the Oromia Media Network; they're journalists. But they were receiving suspicious emails, and we discovered that Ethiopia was spying on them using a different spyware from a different Israeli company called Cyberbit, not NSO.

You think about this. Ethiopia, one of the poorest countries in the world — less than 25 percent internet connectivity — can, thanks to Cyberbit, undertake a global cyber espionage operation, getting inside the devices of more than 20 victims around the world. Like, that's truly unprecedented in terms of the capacity to effectively purchase your own national security agency.

In the past, for Ethiopia to undertake acts of foreign subversion would be incredibly risky, labor intensive, you wouldn't have trained personnel. The risk of exposure is great. But now with a push of a button, they can get inside his head. This is remarkable in terms of the capacity that's been unleashed here.

CH: Is there a biggest offender? Or is it just so widespread now you can't rank them?

RD: No, I don't know if I could rank it. I mean, obviously the sources of the commercial services seem to be right now very much centered on Israel, but I wouldn't suggest that people would think it's just that country. But it's a bit of a chicken-and-egg thing. There's so many more government clients, which increases the value of the companies providing this type of service, which in turn undercuts systems of accountability and independent journalism and civil society, which leads to yet more abuse of power. So it's a kind of self-fulfilling dynamic that's happening right now that we need to somehow first recognize and get out of.

CH: Is it inexpensive? What's your Kmart-grade national security in a box?

RD: That's a really interesting question. And of course there are a lot of potential clients out there that have deep pockets and for them, $10 million is trivial. But then you can also accomplish the same thing very cheaply.

So we produced this report called Dark Basin. We were working for about a year on what we believed was a massive global cyber espionage campaign targeting many, many different sectors of victims. There were politicians, civil society activists working on completely different topics like net neutrality and climate change, lawyers, on and on.

And without getting into the technical details, we have this visibility into this massive network and thought, Is this the Russians? Is it the Chinese? What's going on here? Turns out, at the center of this massive cyber espionage campaign was a single hack-for-hire firm called BellTroX Ltd., based in a small shop in Delhi, India.

Right now there's an ongoing Department of Justice investigation. They've, as far as I know, indicted one lower-level private investigator who actually hired BellTroX, but we don't know who the ultimate clients are because of the way this dark labyrinth is often constructed around these types of operations. You may have a client like a big multinational company that then hires a law firm. The law firm hires a private investigator. The private investigator hires a hack-for-hire company and the hack-for-hire company in this case is based in India.

[Editor’s note: Two weeks ago, that private investigator, Aviram Azari of Israel, pleaded guilty in U.S. federal court to three counts of fraud and conspiracy to commit computer hacking. He was allegedly working on behalf of a German payment firm called Wirecard. ]

CH: So when I first started talking to you years and years ago, we had the Dalai Lama, right? [In 2009, Deibert and his colleagues uncovered a cyber-espionage campaign based in China, targeting the Dalai Lama among hundreds of other victims.]

RD: Yes.

CH: But when you were doing the Dalai Lama project, did you see this coming?

RD: No, I actually did not. It's interesting to think back. It wasn't that long ago, 2008, 2009, I was really focused on this as something governments are doing in-house. And it was only a couple of years later when we first started doing research on the commercial spyware market that it started to dawn on me, Oh, there's this big market for digital espionage. It wasn't until we ourselves were targeted by Black Cube, that it really struck home. Oh, this is more than just electronic espionage we're talking about here. This is something more along the lines of subversion.

What comes to mind when I say subversion? Probably something out of a John Le Carré novel — the CIA and the KGB kind of maneuvering against each other. Subversion is about rotting institutions from the inside out, clandestinely — maybe through fake newspapers or front media organizations, undermining citizens' trust in their own systems of authority from the outside in.

Typically this is something historically that was practiced only by states, but we're living now in a time when, first of all, it’s commercialized and it's open to anyone with the means to pay. So now, if you're a despot or an autocrat or even a corrupt mogul somewhere, you can order up a sophisticated privatized subversion campaign against any target — could be you as a journalist; it could be some political opposition figure — as easy as ordering a sweater on Ebay or Amazon. And to me, this is perhaps the greatest threat to liberal democracy right now when you stand back and you look at the factors leading to all of this. It's like a perfect storm of factors that has led us into this golden age of subversion.

CH: So what do we do about all this?

RD: We need to first recognize the problem. And by that, I mean, serious investigative journalism and research should be focused on what I'm describing here so that we can flush it out from the shadows. Because what we're talking about inherently thrives in the dark.

Secondly, we obviously need governments to act. In many respects, this is not a foreign policy issue as much as it is a domestic issue. Look at the root of the problem, which I believe has to do a lot with kleptocracy. Kleptocracy is facilitated by Western markets, by places like London and the real estate market in London, which is used by oligarchs and plutocrats to hide their assets. Delaware …

CH: New York, too.

RD: Exactly. So we need to tighten up kleptocracy anti-kleptocracy laws and regulations and have law enforcement really go after what is essentially criminal behavior. In so many of the cases that we investigate, we're witnessing crimes here. Part of the problem here is that law enforcement and national security agencies have been mostly focused on conventional foreign threats and not this type of privatized subversion and the role of Western companies in facilitating it — Western law firms, Western private investigators and intelligence agencies. So we need to direct resources towards that.

There are all sorts of tools. Look at the U.S. Commerce Department designating NSO Group, Candiru and, I think, three other hack-for-hire firms on this entity list. [This] means that Americans cannot do business with those entities without a special exemption, which would be very hard to get. Immediately after that happened, Moody's downgraded NSO’s credit rating. That's a tangible impact on that company's viability, and it goes to show how regulations matter. Don't forget these companies that I'm talking about, the ones that are very lucrative, make their investors — it's usually like big private equity and pension funds — a lot of money.

CH: A lot of this reminds me of drone policy, too. People didn't have the imagination that drones could be used in a different way until it was kind of too late. And I'm not even sure we even yet have a very good drone policy.

RD: That’s correct, yeah.

CH: Do you think that this is going to go that same way?

RD: I think it's already gone so far down this harmful alleyway where we see these horrible atrocious results and outcomes related to this industry. We were talking about murder and extortion and blackmail the world over. So we're already there. And to me, this is the most serious threat to liberal democracy right now — by far — is what we're unleashing on ourselves.

The last thing I'll say about enabling conditions that we could clean up here and help mitigate some of these harms is around the kind of social media data ecosystem that's being exploited by these firms. Good example: location tracks. On your iPhone right now, you probably have, I don't know, 40 apps. Each of them give themselves — or try to give themselves — permission to gather information about your location. They then sell that to third parties, usually data analytics firms that you've never heard of, then synthesize and package it up to add other advertisers. Those firms, it dawned on them maybe five, 10 years ago, that law enforcement and government security agencies and private intelligence companies are very lucrative clients. And now they routinely sell to them and they have voracious appetites for following people around.

CH: To push back a little bit, wouldn't law enforcement tell us to look at something like January 6 a bit differently? Isn’t that an example of using digital dust as evidence to bring people to justice?

RD: Sure, there are all sorts of benign applications of intelligence gathering through the data exhaust that's submitted by everyone. That's what we do at the Citizen Lab, right? The reason we were able to publish these reports extensively is because the companies that we're tracking leave breadcrumbs for us and they make mistakes. And the issue is not whether that data exists or not. It's how it's used and whether there's proper oversight to prevent abuse.

But what you have right now is something that's happening as if in a wild west. You can go to vendors and purchase that type of fine-grain detail as a private citizen. Obviously, if you're doing it with a lot of resources and engineers on your team, you can do a lot of harm with that type of data. And if no one's watching you, it makes it worse.

CH: Five years from now, 10 years from now … are we going to have this under control?

RD: I hope so. I don't think we'll have it under control, realistically. I think things are getting worse rather than better, but you know, we have to have a positive thing to focus on. I think if we get our act together, the future remains to be written; we can curb some of this.

Right now, it's like we put the crazy kleptocrats in charge and they're running the world, and we're just not set up to understand it. It's kind of like we're living in a world where Dr. No's rules are what prevails — a world of James Bond villains.

CH: And I'm sorry, what's the happy ending, Ron?

RD: [Laughs] The happy ending is we prevent that from coming about through the very careful systematic measures — from the social media, all the way up to the government regulation around kleptocracy. It's all part of a puzzle.

Will Jarvis

is a podcast producer for the Click Here podcast. Before joining Recorded Future News, he produced podcasts and worked on national news magazines at National Public Radio, including Weekend Edition, All Things Considered, The National Conversation and Pop Culture Happy Hour. His work has also been published in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Ad Age and ESPN.