Should Ukraine rein in its patriotic hackers?

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, a 23-year-old from Kyiv who goes by Vlad decided to fight back. But instead of a rifle, he picked up the weapon he knows how to use best — his computer.

Vlad, who works as an information security specialist, and his friends started to hack Russian websites and leak sensitive data. They also took control of Russian surveillance cameras to monitor the movement of enemy troops.

Vlad declined to go into detail about his activities and asked The Record not to use his last name due to safety concerns — he does not serve in the military and may be criminally liable for his cyberattacks, as well as targeted by Russia.

He is one of thousands of cybersecurity specialists in Ukraine who have found themselves in a similar situation. When the war began, they joined the digital fight against Russia — some working individually and some as part of a group, including IT Army, a hacktivist collective that organizes distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks on Russian sites.

Ukrainian government officials distance themselves from specific attacks carried out by these groups, but praise hacktivists’ achievements and openly encourage tech-savvy citizens to join their ranks. There is no discussion between the two sides about the consequences of such attacks.

Now with the war coming up on its one-year mark, the Ukrainian government is indicating it’s time to better regulate cyberspace.

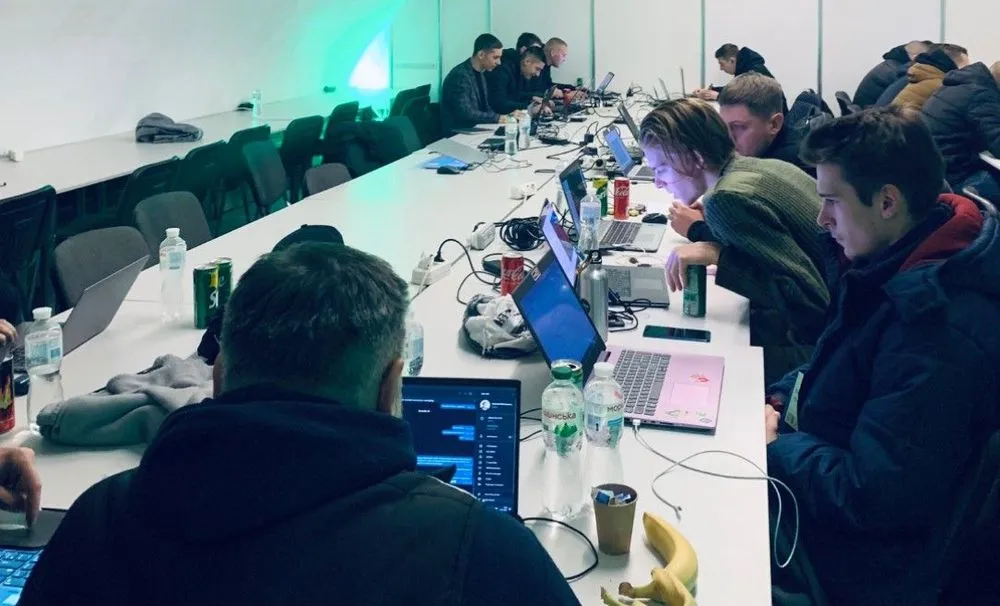

Last week, the Ukrainian government invited about 300 cybersecurity specialists from the public and private sectors to the National Defense Hackathon – a three-day event organized in the Kyiv metro, which is protected from Russian missiles and has uninterrupted access to electricity amid nationwide blackouts.

For the event, the metro station was turned into a cyber hub with bean bag chairs, coffee machines and ‘hacker snacks’ — Snickers, burgers and energy drinks.

All kinds of people attended the hackathon: experienced cybersecurity specialists, students, state security officials, and ethical hackers. They worked together on services that could help Ukraine fight Russia on the cyber front — for example, systems for collecting and analyzing large volumes of data to identify Russian soldiers.

The event was also an opportunity to discuss the challenges of the cyberwar, including the legal status of patriotic hackers. As it turned out, not everyone agreed.

Dangerous phenomenon

The ІТ Аrmy was an obvious way the Ukrainian tech community could respond to the Russian war, said Yegor Dubinsky, deputy digital transformation minister of Ukraine, speaking during the event at the Kyiv metro. Everyone wanted to help, and there were no questions about what was allowed and what was not, he said.

Although IT Army is not the only Ukrainian hacktivist group fighting against Russia, it has received the most publicity and it attracted hacktivists globally who joined it in the first days of the war.

Some foreign experts have been wary of this mobilization. They say that IT Army stands “in stark violation” of UN and NATO’s norms of state behavior in cyberspace and “challenges existing norms on civilian participation in the war,” according to a paper by cybersecurity researchers Jason Healey and Olivia Grinberg published in September on Lawfare.

Researchers have argued that offensive cyber operations should be ordered by the president or the military and conducted by legally authorized government personnel. Otherwise, they can be considered “illegal activities by criminal groups.”

Ukrainian state officials agree that hacktivists can easily find themselves in a legal gray area.

“Any army must have a legal status. Otherwise, the world may consider it a terrorist organization,” said Oleksandr Fediyenko, a Ukrainian lawmaker and cybersecurity expert.

According to him, the Russians are collecting evidence to file international lawsuits against Ukrainians who are actively fighting in cyberspace, calling them terrorists.

So far, there has been no consensus in Ukraine on how to regulate hacktivists.

Dubinsky compared them to civilians who joined the Territorial Defense Forces in the early days of the all-out war. But not everyone agrees with this — after all, the Territorial Defense Forces are a military reserve component of Ukraine’s Armed Forces subordinate to the Defence Ministry.

Civilians and military should not be equated, according to Bohdan Chumak, adviser to the defense minister. “International humanitarian law says that any offensive actions by people who do not have the status of a combatant are considered a war crime and can be prosecuted by law,” he said.

Impractical laws

Although NATO recognized cyberspace as a domain of military operations alongside the traditional domains of air, land, and sea, there are still no clear rules that would allow a state to respond to a cyberattack in the same way as to a physical attack, according to Natalia Tkachuk, head of the Information Security and Cybersecurity Service.

For example, there has been much debate over whether Albania should invoke NATO’s Article 5 in response to a cyberattack by Iran, drawing all NATO member states into a confrontation with Tehran.

The dynamics of the cyber war between Ukraine and Russia are more complicated and leave many questions, according to Tkachuk. For example, when Ukrainian hacktivists attack Russian propaganda TV to show Russians the truth about the war in Ukraine, they technically violate international law, as the media is a civilian target.

“But Russia constantly bombards Ukraine's critical and civilian infrastructure, so why can't Ukraine attack back?” Tkachuk said.

Possible solutions

In order to protect Ukrainian hacktivists from persecution at the international level, their activity must first be decriminalized in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian Criminal Code contains several articles that prohibit the creation of malicious software and illegal interference with computer systems. Some experts agreed that Ukraine should amend its criminal code and make exceptions for cyber actions carried out in the interests of the country's cyber defense.

The next step is to create the Ukrainian cyber forces as part of the Armed Forces, according to Tkachuk. The Ukrainian government had discussed this long before the start of the war, but there is still no law that would determine the legal status, funding, and staffing of the cyber forces.

Ukraine should also discuss the issue of hacktivist prosecution with the international allies who support the country in the fight against Russia, Tkachuk said, ensuring they are granted leniency in the short-term.

No matter what the new laws are for the Ukrainian cyber army, international partners must know and understand them.

“If Ukraine wants to become a NATO member, it must meet its standards,” said Chumak. “Some of these standards are evolving because of the war in Ukraine, but one of the key principles is that military actions should be the responsibility of the military, not civilians.”

And although government officials have not made a clear decision on the regulation and protection of cyber volunteers, hacktivists are not too concerned about the possible consequences of cyberattacks against Russia.

“As a civilian, I don't mind taking part in ‘hostilities’ since the escalation has already happened and the crazy dictator is threatening the world with nuclear weapons,” Sean Townsend, press secretary of Ukrainian Cyber Alliance, wrote on Telegram.

“As a patriotic hacker,” he went on, “I responsibly declare that we will fucking hack both the military and civilian infrastructure of Russia, especially since the Russians themselves do not see the difference between them [in Ukraine].”

Patriotic hackers are ambivalent about possible regulation. Some believe it would give the government too much control and limit their actions in cyberspace. Others, like Vlad, agree that the current legislation is imperfect and needs to be changed.

But for now, Vlad said he would continue to fight on the cyber front regardless of the consequences. "I'm not afraid because I'm fighting for the truth and the truth is on my side," he told The Record.

Daryna Antoniuk

is a reporter for Recorded Future News based in Ukraine. She writes about cybersecurity startups, cyberattacks in Eastern Europe and the state of the cyberwar between Ukraine and Russia. She previously was a tech reporter for Forbes Ukraine. Her work has also been published at Sifted, The Kyiv Independent and The Kyiv Post.