Researchers infiltrate Qilin ransomware group, finding lucrative affiliate payouts

Cybersecurity researchers managed to infiltrate the Qilin ransomware group, gaining an inside look at how the gang functions and how it rewards affiliates for attacks.

The ransomware-as-a-service group (RaaS) — also known by the name “Agenda” — initially emerged in July 2022, attacking a slate of healthcare organizations, tech companies and more across the world.

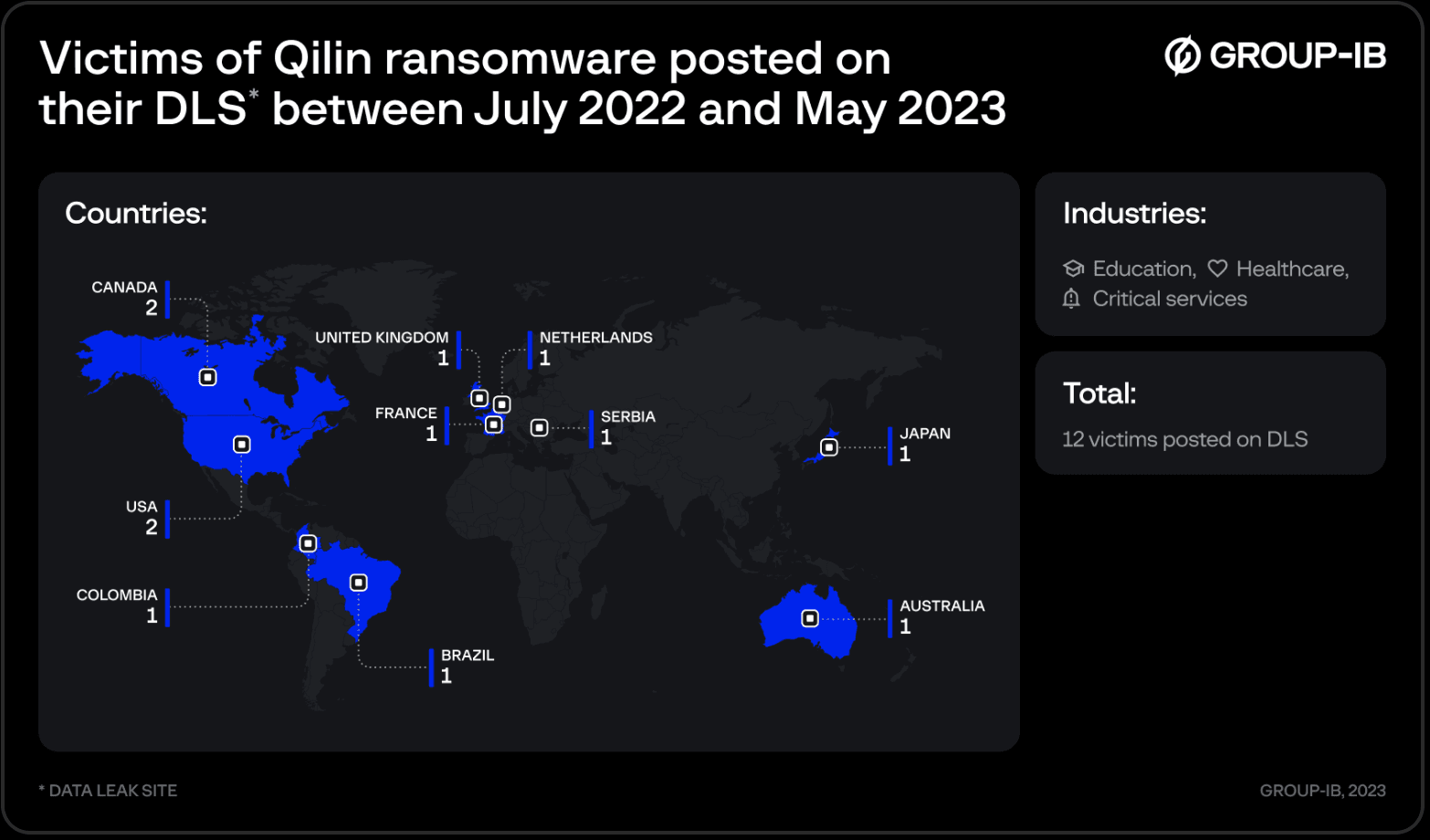

They have victimized at least 12 organizations since July 2022 from Canada, the United States, Colombia, France, Netherlands, Serbia, the United Kingdom and Japan. The group explicitly tells affiliates it will not attack countries within the Commonwealth of Independent States, including Russia and several neighbors.

The cybersecurity software company Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence team was able to infiltrate the gang in March, gaining access to their administrative panel and detailed information about how their affiliates are paid. Researchers publicized the infiltration and what they gleaned from it in a report released this week. Group-IB did not say how it got an inside look at the group or how long it had access to Qilin’s RaaS program.

According to the report, the administrator of Qilin’s RaaS program told undercover researchers that affiliates take home 80% of ransom payments that are $3 million or less. For any ransom payments above $3 million, affiliates get 85% of the payment.

The security researchers confirmed the payment structure with another user they tracked down through the underground forum RAMP.

Craig Jones, vice president of security operations at the detection and response provider Ontinue, said the figures dwarf those seen in the past for RaaS models. For example, affiliates of the GandCrab ransomware group would only take home about 60% to 70%, after charging anywhere from $500 to $1,200 for access to the ransomware.

REvil operated similarly, with affiliates getting the same cut as GandCrab. That figure could rise to 80% depending on the number of ransoms brought in by the hacker. Affiliates of the NetWalker ransomware had an even higher entry cost, meanwhile — typically between $1,200 and $1,800 — but would get up to 80% of a ransom. Qilin isn't the only group offering affiliates exorbitant cuts of ransoms, however. Cybersecurity expert Heath Renfrow said BlackCat ransomware affiliates have also allegedly been earning 80% to 90% of ransoms.

Group-IB did not respond to requests for comment about the cost for access to Qilin ransomware.

“Astoundingly high profit margins, epitomized by the 80-85% share pocketed by Qilin affiliates, spawn a prosperous underworld of cybercrime, exploiting the weak points in global enterprises,” Jones said.

The affiliate panel

Group-IB said affiliates are given access to a panel that is divided into various sections for particular tasks. One of them, titled “Targets”, has information about companies that have been attacked, including the size of the ransom.

The researchers found that the ransomware attacks are customized for each victim, allowing hackers to change the filename extensions of encrypted files and more.

Affiliates are allowed to configure a sample of Qilin ransomware using a builder and can access the ransom waiting period, as well as company revenue and other information pulled from Zoominfo for posting a victim to the group’s leak site.

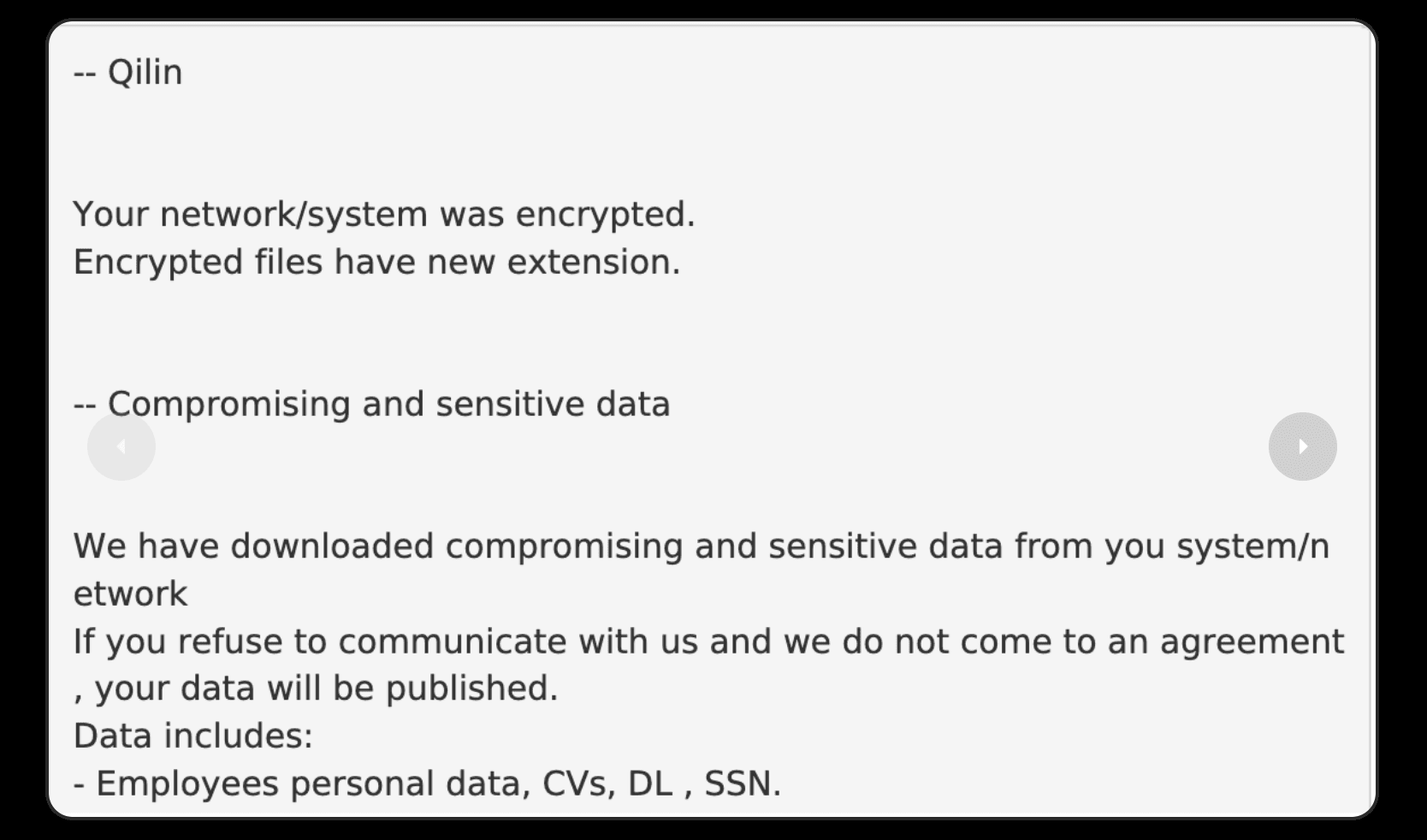

A ransom note posted on the Qilin leak page. Image: Group-IB

A ransom note posted on the Qilin leak page. Image: Group-IB

The gang has separated itself from other groups because its ransomware is written in the Rust and Go programming languages — a feature that makes it more versatile and difficult to analyze or detect.

“The Rust variant is especially effective for ransomware attacks as, apart from its evasion-prone and hard-to-decipher qualities, it also makes it easier to customize malware to Windows, Linux, and other OS,” the researchers said.

“It is important to note that the Qilin ransomware group has the ability to generate samples for both Windows and ESXi versions.”

Most victims are initially targeted through phishing emails, with threat actors eventually moving laterally throughout a system searching for data to encrypt. Ransom notes are placed in every infected directory, providing victims with information on how to “buy” the decryption key.

The actors typically take steps to make it harder for victims to recover, stopping certain server-specific processes or rebooting systems.

Qilin’s system is representative of how simple things have become for those interested in getting involved with ransomware, said Matthew Psencik, of endpoint management company Tanium.

Hackers no longer have to write their own malware, build attack infrastructure, and create custom phishing campaigns, Psencik explained, but can simply pay their way into a group for access to a RaaS product.

“This low barrier to entry will allow unsophisticated criminals to prey on organizations that don’t have adequate defenses or proper backups in place to force a ransom payment,” he said.

Group-IB’s report noted that the Qilin ransomware operator’s affiliate program is not only adding new members to its network but is weaponizing them with upgraded tools, techniques, and even service delivery.

Cybersecurity expert Renfrow added that the RaaS affiliate structure has advantages to those of organized criminal actors because threat actors are tough to pin to a specific country of origin, making it difficult to place them on a “do not pay” prohibition list.

“By offering higher cuts of the pie, these organizations can both evade the payment bans and inspire more criminals to start new affiliates, adding to larger overall profits,” he said.

Jonathan Greig

is a Breaking News Reporter at Recorded Future News. Jonathan has worked across the globe as a journalist since 2014. Before moving back to New York City, he worked for news outlets in South Africa, Jordan and Cambodia. He previously covered cybersecurity at ZDNet and TechRepublic.