RansomClave project uses Intel SGX enclaves for ransomware attacks

Academics have developed a proof-of-concept ransomware strain that uses highly secure Intel SGX enclaves to hide and keep encryption keys safe from the prying eyes of security tools.

Named RansomClave, the project was developed by Alpesh Bhudia, Daniel O'Keeffe, Daniele Sgandurra, and Darren Hurley-Smith, all four from the University of London.

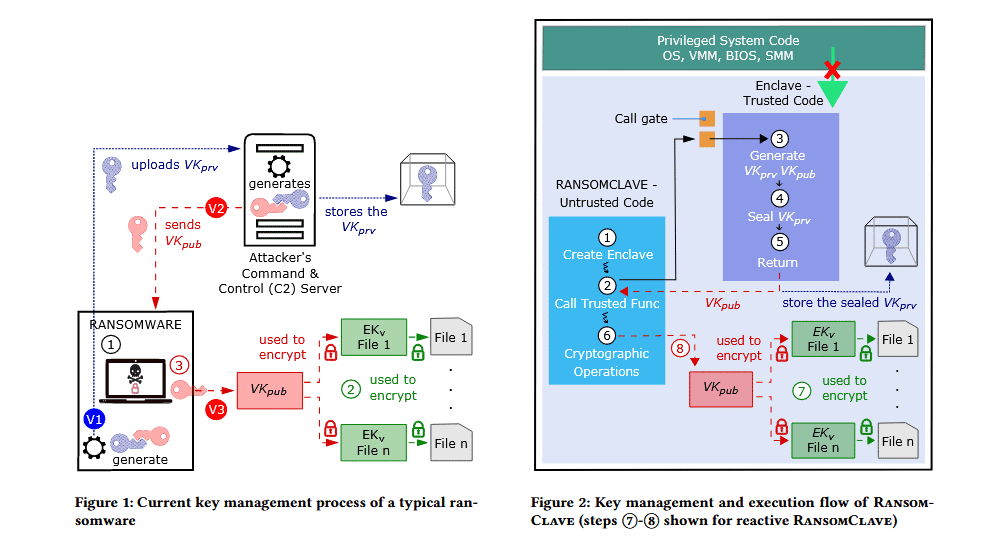

"A typical ransomware attack lifecycle goes through four main phases: installation, unique public/private key generation, encryption (with symmetric keys), and extortion/private key release," the researchers said in a research paper published last month.

"For a successful operation, the private key created in the second phase needs to be securely stored and only released in the last phase once the victim has paid the ransom," the team said.

Today, several ransomware strains generate and store these encryption keys in untrusted areas of a computer's memory and then discard the key after the encryption process ends, or the key gets deleted when infected systems are rebooted.

In rare cases, victims can get very lucky when bugs in the ransomware code or a security team's prompt response can lead to situations where incident responders can extract a copy of these keys from a computer's memory before the keys are wiped, and then use those same keys to decrypt the victim's locked files.

Could ransomware gangs benefit from CPU enclaves?

The RansomClave project was born from the research team's curiosity regarding the possibility of ransomware strains protecting their encryption keys during an attack by leveraging a technology called a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), commonly used in cloud environments.

Also known as CPU enclaves, TEEs are separate areas inside a processor where the OS or local apps (such as ransomware) can load and run code that can't be accessed by other local processes.

RansomClave is the result of the team's curiosity. It is a proof-of-concept ransomware strain that uses Intel SGX enclaves to safely handle encryption keys.

In addition, it also uses the enclave to automatically decrypt files on the infected host when the enclave detects that a payment to a specific address on a cryptocurrency blockchain has been made.

For pretty obvious reasons, a project like RansomClave would be of great interest to ransomware gangs.

"We plan to keep all the [RansomClave] code private to prevent potential abuse," Alpesh Bhudia, one of the four researchers behind the project, told The Record in an email conversation last week when asked about the potential Pandora's box his team was opening.

Would ransomware gangs be interested in RansomClave?

But the premises behind the RansomClave project have also changed in recent years, especially with the rise of ransomware gangs that are now orchestrating targeted attacks inside corporate networks, many times connecting manually to infected networks, in what security researchers call hands-on-keyboard attacks.

In an email last week, Mark Loman, Director Of Engineering at Sophos, told The Record why projects like RansomClave, while ingenious, would likely not be adopted by real ransomware gangs, as they've already changed how they carry out these attacks. He explained:

RansomClave aims to break a recovery approach called PayBreak, which they reference and was documented in another research paper from 2017. For PayBreak to work, the ransomware must use the Windows CryptoAPI, monitored by PayBreak. Mentioned ransomware families that use CryptoAPI are the original CryptoLocker and CryptoWall – both gone since years. In real-world attacks there is no PayBreak software on the machines, so memory must be scraped instead, hoping it still contains any encryption keys.

But ransomware has evolved and is regularly tailored and human-operated / targeted. In these attacks, the ransomware is typically generated for each victim. Let me explain why that is a problem.

Generally, today, ransomware generates a symmetric key for each file it encrypts, and that symmetric key is RSA asymmetric encrypted with a public key. To decrypt any files, you'd need the asymmetric encryption's private key. Only the public key is embedded in the ransomware and loaded into memory. The private key is never sent to the victim and can therefore not be found in memory; the public-private key pair is generated far away on the machine of the ransomware author. Even if you would be able to recover a symmetric encryption key, know that it is for one file only as that key continuously changes and is overwritten or removed from memory when encrypting subsequent files; they do not remain in memory.

For ransomware gangs today, storing the encryption keys in a CPU enclave makes no sense. RansomClave looks to solve a problem that doesn't exist anymore.

The research team is scheduled to present their findings tomorrow at the ARES conference. A copy of the team's paper, titled "RansomClave: Ransomware Key Management using SGX," is also available for download via ArXiv.

Catalin Cimpanu

is a cybersecurity reporter who previously worked at ZDNet and Bleeping Computer, where he became a well-known name in the industry for his constant scoops on new vulnerabilities, cyberattacks, and law enforcement actions against hackers.