Peru’s presidential election turns into a test for social media platforms

The runner-up in Peru’s presidential run-off is waging a Trump-style disinformation campaign aimed at preventing the country’s electoral authorities from certifying her defeat. But there's one key difference: Social media companies have taken few steps to label, downgrade, or remove misleading content, sparking a debate about when and how those firms should intervene to prevent baseless allegations of electoral fraud from spiraling into civil unrest.

Since her defeat became apparent in early June, Peru’s right-leaning presidential candidate, Keiko Fujimori, has sought to nullify roughly 200,000 votes in rural areas that overwhelmingly voted for her opponent, the leftist Pedro Castillo. While Peru’s electoral authorities slowly rejected those claims—and now, Fujimori’s appeals to those claims—the candidate has continued using social media to perpetuate the myth of a stolen election.

“Why isn’t what happened with Trump happening with Keiko?” asked Paulo Rosas, the coordinator of PeruCheck, a Peruvian fact-checking consortium that includes regional publications as well as some of the country’s largest newspapers. “I suppose elections in the US are one thing, and elections elsewhere are another,” he said.

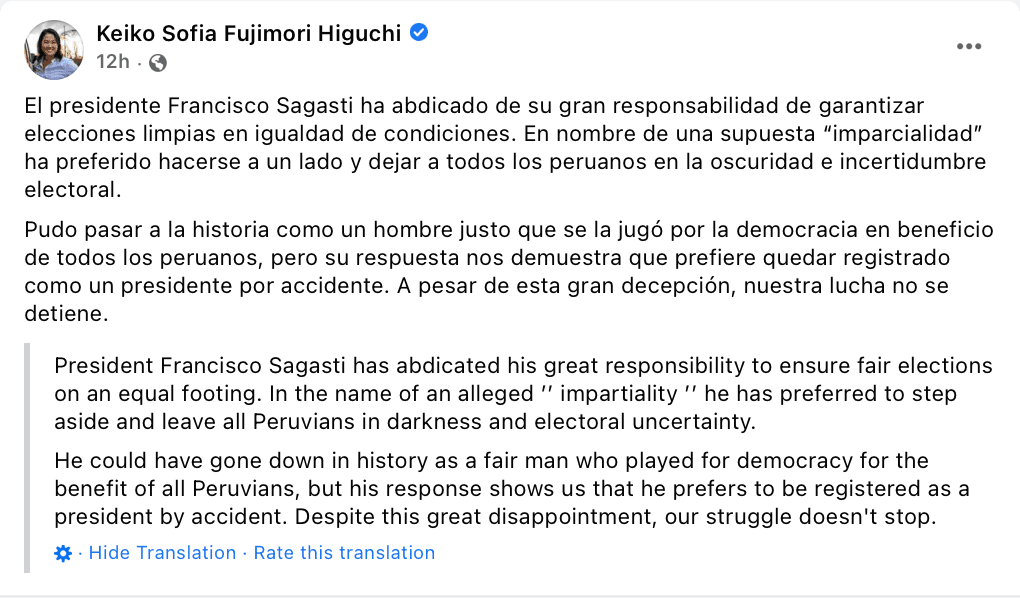

Fujimori and her allies insist they are seeking transparency. But since a bevy of international observers, including the EU, the US State Department, and the Organization of American States, published statements validating the integrity of Peru’s elections, Fujimori’s efforts have turned desperate.

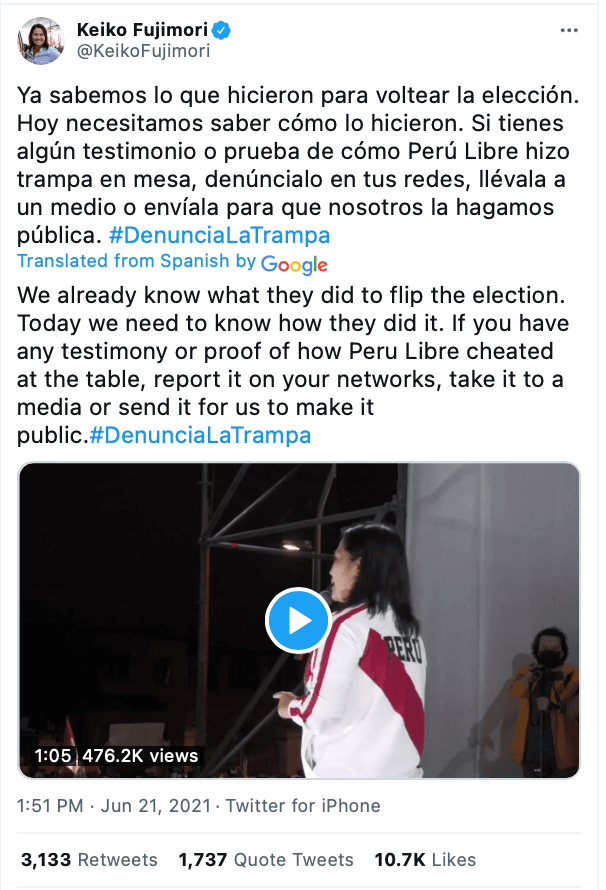

For example, on June 21, Fujimori implored her 2 million Facebook followers and 1.2 million Twitter followers to text her campaign evidence of the fraud “we already know” happened. Fujimori, the daughter of a Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori, faces a 30-year prison sentence on charges of money laundering if she loses the election.

For social media companies, the failure to implement even modest steps to address the Fujimori campaign’s weeks long effort to overturn the Peruvian election raises questions about their ability to combat deceitful information in regions of the world that command little attention, or fill few pocketbooks, in Silicon Valley or Washington, D.C.

Asked whether they had taken any steps against specific accounts, including Fujimori’s, that repeatedly violated each platform’s election-related disinformation policies, Twitter and Facebook referred The Record to prior and ongoing efforts to work with Peruvian media and election authorities. For its part, Facebook cited its third-party fact-checking program and its efforts to fund local fact-checkers, including PeruCheck.

YouTube, Telegram, and TikTok, also popular among the Fujimori campaign, did not respond to requests for comment.

In general, social media companies take a more lenient approach toward moderating content by political figures, holding such material to a different standard because they judge the content, good or bad, important for the public to know. But the companies also acknowledge that such decisions are context dependent, meaning they might intervene against material that indirectly contravenes company policy.

Several local fact-checkers have stepped into the void left by social media companies in Peru. Alongside PeruCheck, Ama Llula, a fact-checking consortium organized by Peru’s independent media, has developed creative methods to counter viral misinformation. The partnership has used Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp and Facebook to distribute fact-checking memes and live or recorded audio discussions around the day’s news.

Such entities nonetheless face improbable odds against Peru’s disinformation problem, said Patricio Ortega, the founder of El Filtro, one of the fact checkers that works with Ama Llula.

“We are like Don Quixote fighting the windmills,” said Ortega. “We just don’t have sufficient reach. And second, because when lies ring true at an emotional level, they can travel much faster than the truth.”

With their control over content delivery, social media companies can wield far more influence over on-platform discourse than the savviest fact-checkers. Nonetheless, many Peruvians are skeptical that social media companies have the expertise to make sophisticated interventions amid the country’s complex and polarized political environment.

Rider Bendezú serves as Director of Verificador, the fact-checking unit at one of Peru’s largest newspapers, La República. Since June of last year, Verificador has represented the sole Peruvian fact-checking entity in Facebook’s third-party fact-checking program, through which the company enlists accredited entities to adjudicate complaints surfaced by its users.

Bendezú explained that on social media, Fujimori is savvy about toeing the line between falsehood and opinion. Though he suggested Facebook could do more to fact-check speeches that get posted to the social network, he said that taking more aggressive action against her posts might backfire and feed a narrative of victimization.

“We are like Don Quixote fighting the windmills,” said Patricio Ortega, the founder of fact checking organization El Filtro.

“We do fact-checking that can upset some people. We do it because we know we’re fulfilling our obligations to the truth,” he said. “But asking social media companies to reduce the visibility of Fujimori’s posts, yes, I think that would be much more controversial.”

Miguel Morachimo, the Executive Director of Hiperderecho, a Lima-based non-profit that conducts research, teaching, and activism on digital rights, agrees that it would be unwise for social media companies to take a heavier hand in Peruvian content moderation.

Instead, he pointed to the role Peru’s traditional media had played in abetting Fujimori’s disinformation campaign. Whereas major American media companies quickly accepted the legitimacy of Trump’s defeat, he observed, Peru’s mainstream media has continued giving oxygen to Fujimori’s accusations of fraud.

“If you cannot trust the principal institutions, the media, and the political actors to be reliable sources for information, who are foreign social media companies to play that role?” he said. “I think it would be a mistake to pin this on them. It is really a systemic problem in Peru’s information landscape.”

Complicating that landscape, Fujimori’s legal team has overwhelmed Peru’s election authorities with an unprecedented number of procedural appeals. As a result, the country’s central electoral authority, the JNE, has yet to declare a winner in the election.

There is no suspense surrounding the outcome. Even if she wins every remaining case before the JNE, she cannot overcome her 44,176-vote deficit with Castillo.

None of the social media companies that The Record contacted answered when asked whether the delay in the JNE affected their content moderation decisions in Peru.

All the while, the delay has bought Fujimori time to organize rallies and marches, to pressure election officials and the government, and to otherwise seed distrust in the results of the election—a situation that loosely parallels the environment in the United States preceding the January 6 Capitol Riot.

Verónica Arroyo, a Lima-based Policy Associate for Access Now, a non-profit that promotes and defends digital rights, said that information landscape in Peru has grown so toxic since the presidential run-off that many Peruvians no longer know what media they can trust

Yet Arroyo cautioned against overreaction. In the name of combating disinformation, she said, many governments across Latin America have been pushing legislation that could be abused to quash legitimate criticism or dissent on social media.

“We have to be careful about giving platforms or governments more power,” she said. “Those measures can end up harming marginalized voices. The most important step we can take is to position more diverse voices in the fact-checking world.”

Morachimo, the Executive Director of Hiperderecho, suggested social media companies would have an easier time dealing with this type of disinformation once the JNE certifies the election, a process that could take another week. But he also warned against ignoring the underlying drivers of disinformation.

“If we focus too much on what platforms should do, we’ll miss the larger picture of who is engaging and creating this information, and why they are successful,” Morachimo said. “This stuff works because people don’t trust our institutions, because people already mistrusted our election system.”