New CPU side-channel attack takes aim at Chrome's Site Isolation feature

A team of academics from universities in Australia, Israel, and the US has successfully mounted CPU side-channel attacks that recover data from Google Chrome and Chromium-based browsers protected by the Site Isolation feature.

Named Spook.js, the discovery is related to the Meltdown and Spectre attacks disclosed in January 2018, two CPU design flaws that could allow malicious code running on a processor to retrieve data from other apps or from secure areas of a CPU.

While only demonstrated at a theoretical level, both attacks showed that the current design of modern CPUs did not take security seriously. While Intel and AMD committed to altering their future CPU designs to incorporate more security features, software vendors also responded by hardening their applications in order to prevent easy exploitation.

Among the first to do so was Google, which chose to add a new feature inside Chrome named Site Isolation. This feature works by separating JavaScript code on a per-domain basis in order to prevent malicious sites from running a JavaScript-based Spectre attack and steal information from the user's other opened tabs.

However, the Spook.js team realized that the current Site Isolation feature does not go far enough. Researchers said that while Site Isolation separates domains like example.com from attacker.com, it does not separate subdomains, such as attacker.example.com from login.example.com.

Spook.js exploits this hole in the Site Isolation design, which apparently Google knows, but about which it also can't do anything about, since separating JavaScript code at the subdomain level would also cripple about 13.4% of all internet sites.

Spook.js attack demonstrated in several scenarios

Starting from this premise, the research team said they successfully developed Spook.js, a JavaScript tool that can mount Spectre-like side-channel attacks against Chrome and Chromium-based browsers running on Intel, AMD, and Apple M1 processors.

The tool only retrieves data from the same subdomains as the attacked website, and it works only if the attacker manages to plant their Spook.js code on the targeted website. While this might sound like a limitation, researchers said that multiple websites allow users to create subdomains and run their own JavaScript code — such as Tumblr, GitHub, Bitbucket, and many others.

Furthermore, sites can also be hacked, but this scenario was not explored during the research as it would have broken ethical research norms — but it is still a case that should be considered.

Below are some of the successful experiments carried out by the research team:

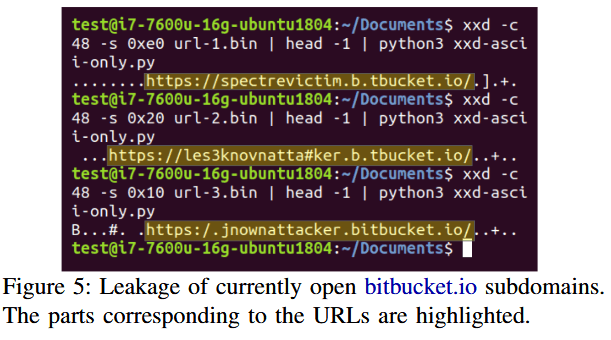

Bitbucket example - determining other open tabs

Researchers created a Bitbucket account where they hosted the Spook.js code on a subdomain in the form of username.bitbucket.io.

They used a variant of the Spook.js code to see what other Bitbucket subdomains a visitor had open in their browser.

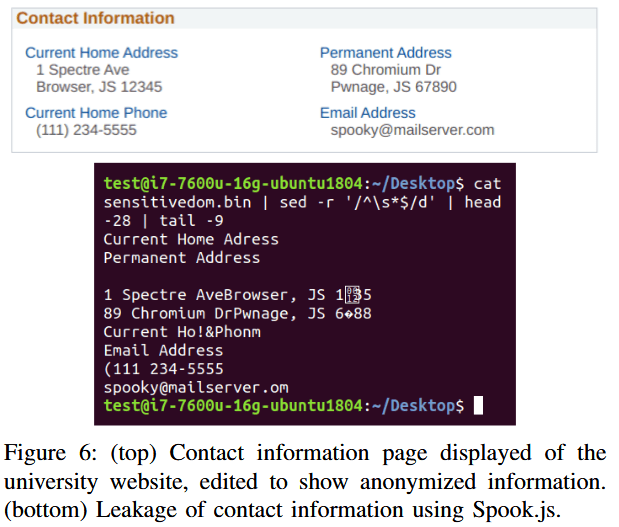

University portal example - retrieving DOM data from other subdomains

The research team also created a subdomain on a university portal, which can be created for students and professors, where they hosted the Spook.js code.

After asking a university employee to access their malicious page, they were able to retrieve information from the university's HR portal, hosted on another subdomain, such as personnel records. This experiment was done under the supervision of the university's IT department — for ethical reasons.

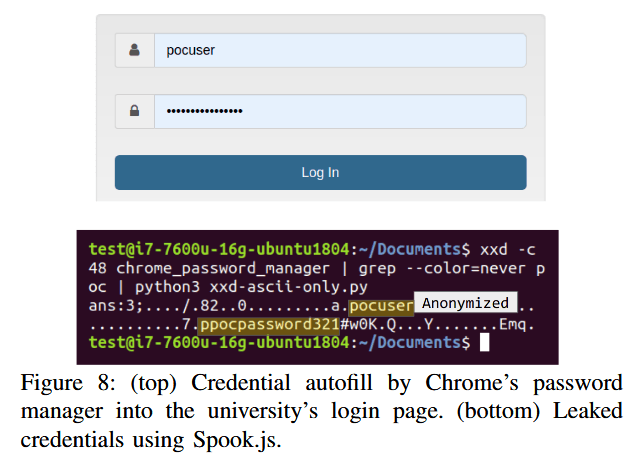

University login portal example - retrieving passwords

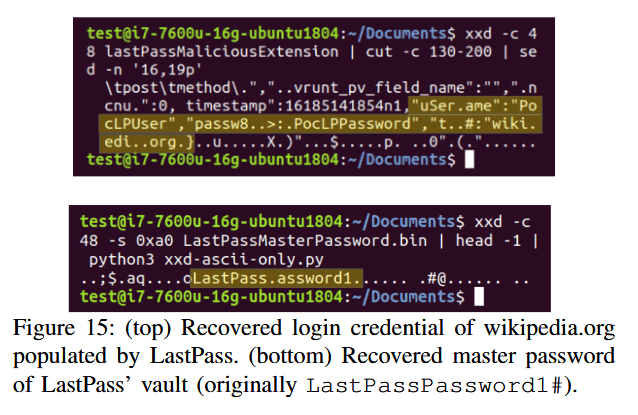

The same setup as above was also used to attack the university's login portal, from where researchers said they were able to retrieve login credentials that were auto-filled by Chrome's password manager.

In a variation of this experiment, researchers said Spook.js also retrieved passwords from the university's login portal that were auto-filled by the LastPass password manager (Chrome extension).

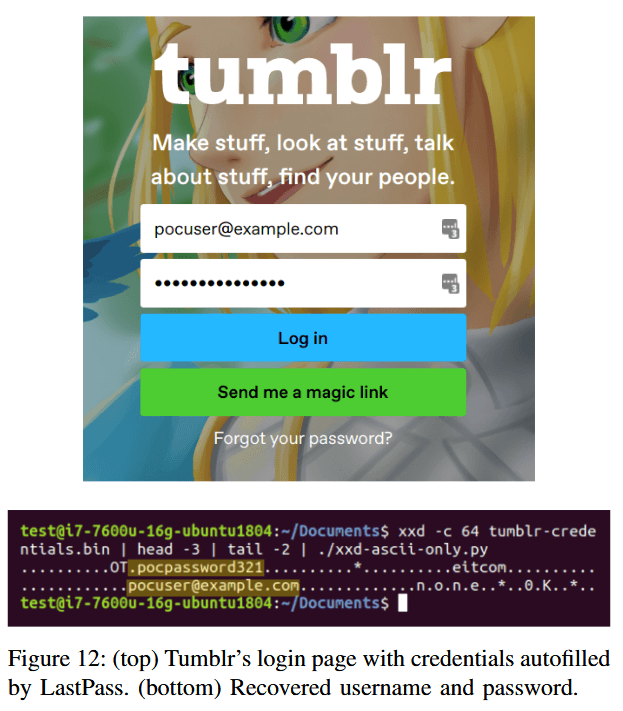

Tumblr example - stealing passwords with iframes

Furthermore, in another experiment, the researchers said the victim didn't even need to have the university login portal active, as they could simply load it inside an iframe component hidden somewhere on their attack page.

This premise can also be applied to other attack variants, with the attackers luring a victim on their domain, and opening the desired subdomain inside an iframe, and then recovering the victim's data from that domain using Spook.js.

This same attack was also replicated on Tumblr, a blogging platform that lets users create blogs and add their own JavaScript code via blog templates, hence permitting Spook.js attacks on all the other Tumblr users.

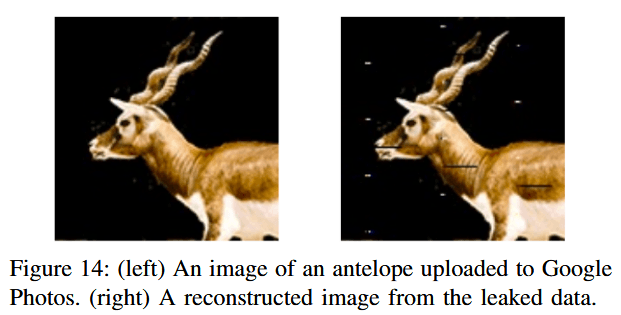

Google example - attacking Google services

But not all sites that support subdomains have data worth stealing. One of the sites that have both is Google.

In another experiment, researchers said they also created a website on the Google Sites website hosting service, where they uploaded Spook.js to create a malicious page.

Using Spook.js, the researchers said they could recover images uploaded to a victim's private Google Workspace or Google Photos accounts.

Chrome extension example - stealing everything

And last but not least, researchers said they packaged Spook.js into a Chrome extension that they loaded into a Chrome browser.

Since all extension code runs in the same process, Spook.js was able to retrieve data from other extensions, which in their experiment was passwords that were being auto-filled by the LastPass extension in a victim's browser.

Of all the attacks, this was deemed the most severe, as users tend to run a large number of extensions, many of which have intrusive permissions and access to all of the user's data, which, in this case, would be up for grabs for the Spook.js code.

Google implements Site Isolation for extensions

The researchers said they notified all the affected companies whose products they tested during their research, which included Intel, AMD, Google, Tumblr, LastPass, and Atlassian.

Google was the one who took the team's findings the most seriously, and recognizing the danger of a Spook.js attack on its extensions ecosystem, announced in July that it would implement the Site Isolation feature at the extension level, separating each extension's JavaScript code from each other.

"This blocks the extension variant of our attack (Section 6), but does not help with other cases," Daniel Genkin, one of the academics behind Spook.js, told The Record in an email this week.

"We appreciate the work of the research community, and recently made changes to Site Isolation that help us protect against this type of attack," a Google spokesperson told The Record when inquired about the researchers' findings.

Asked about the importance of their findings and Site Isolation, Genkin had the following to say:

I would not say Spook.js breaks site isolation. If anything, it does not, as sites that are properly isolated remain out of reach. Instead, what we show is that in some cases, the way Chrome implements strict site isolation has issues. In particular, the fact that all pages in a domain are considered mutually trusting is problematic, as one page can still attack another, which results in information leakage. We demonstrate exactly such scenarios in Section 5.

Additional details will be available later today on the Spook.js website and in a research paper titled "Spook.js: Attacking Chrome Strict Site Isolation via Speculative Execution."

Article updated with Google's statement.

Catalin Cimpanu

is a cybersecurity reporter who previously worked at ZDNet and Bleeping Computer, where he became a well-known name in the industry for his constant scoops on new vulnerabilities, cyberattacks, and law enforcement actions against hackers.