Neural data privacy an emerging issue as California signs protections into law

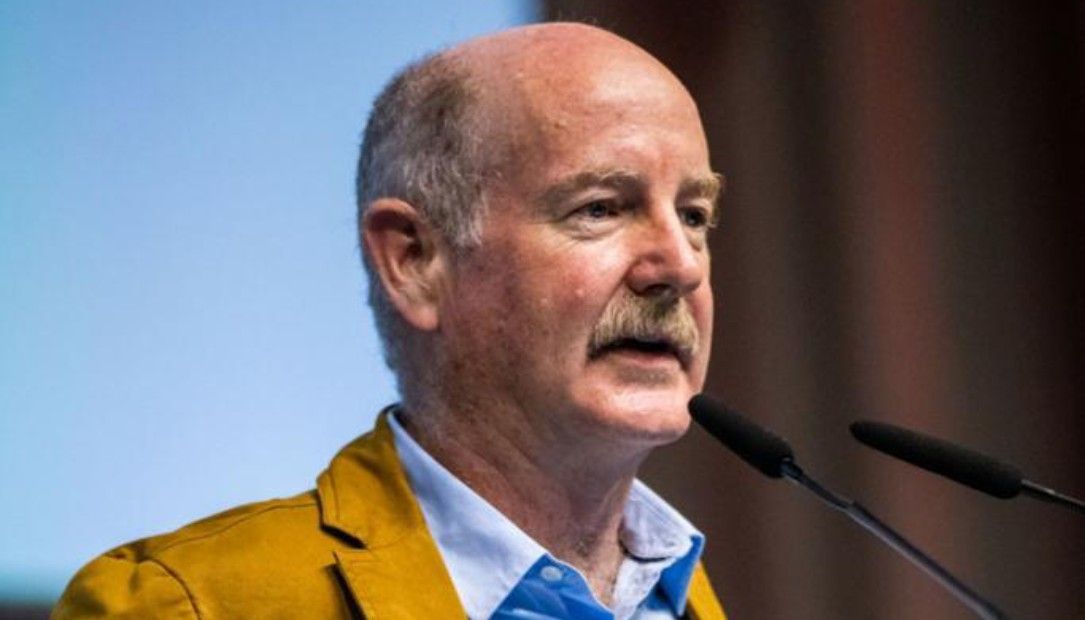

Neurobiologist Rafael Yuste had what he calls his “Oppenheimer moment” a decade ago after he learned that he could take over the minds of mice by turning on certain neurons in their brains with a laser.

While initially excited about how the discovery might help schizophrenics suffering hallucinations, Yuste’s euphoria dissipated once the breakthrough’s serious implications for humans — whose neural data could one day be manipulated in the same way — became clear to him.

Neural data is already being harvested from humans — much of it from gamers and meditation practitioners — and sold to third parties, Yuste said in an interview.

Absent strong regulation, data brokers could soon be able to sell neural data they have harvested and stored in databases cataloging individuals and their “brain fingerprints” on a mass scale, said Yuste, who is a professor of neuroscience and the director of the NeuroTechnology Center at Columbia University.

“It could be a wholesale elimination of privacy because the brain is … the organ that generates all of your mental activity,” Yuste said. “If you can decode your mental activity, then you can decode everything that you are — your thoughts, your memories, your imagination, your personality, your emotions, your consciousness, even your unconsciousness.”

Inspired to launch an organization dedicated to protecting the neural data of humans, Yuste partnered with a prominent human rights lawyer to establish the NeuroRights Foundation in 2021 and has since been engaging with lawmakers nationwide on the need for regulation.

Image: Rafael Yuste

The group has made some inroads: Legislation expanding existing privacy protection laws to include neural data was signed into law by California Gov. Gavin Newsom on Saturday after passing through both chambers of the state’s legislature in unanimous votes.

Under the law, consumers can now request, erase, correct and limit what neural data companies collect from them.

In April, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis signed the nation’s first such law, which, like California, expanded the definition of “sensitive data” covered under the state’s privacy law to include data produced by the brain, spinal cord or nerve network.

Yuste played a key role in getting the California and Colorado laws passed and said he is now speaking with legislators in four other states about passing similar measures. At his urging, Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) has included a neural data privacy provision in the latest draft of a comprehensive data privacy bill she introduced in April, Yuste said.

Privacy advocates believe the need for regulation is urgent.

Tech giants are now exploring how to reap neural data. Last September, Apple filed for a patent for a future iteration of its AirPods product that can scan brain activity by tapping into users’ ears, while Meta is reportedly exploring a new “neural interface” smart watch.

Companies already pulling data from consumers’ brains are now sharing the data with third parties, according to a report released by Yuste’s foundation in April. For the most part they do it by signing up consumers to wear electroencephalogram helmets, which have traditionally been used to diagnose epilepsy, brain tumors or strokes, Yuste said.

One of the 30 companies the foundation studied has collected millions of hours of brain signals from consumers, Yuste said. All but one of the companies “took possession” of the brain data collected, and more than half sold the brain data to unknown third parties.

“It could be the Russian military, it could be any third party and obviously, once you do that, the third party is not bound by the consumer user agreement,” Yuste said. “Brain data could not be less protected.”

For now, many of the contexts in which brain data is used are “low level,” Yuste said, but the field is rapidly advancing.

In December, a team of scientists were able to decode the “mental speech,” or silent thoughts, of a volunteer, he said.

The scientists’ discovery could lead to useful consumer products that allow humans to dictate or make Google searches by merely thinking, Yuste said. But the experiment also shows humans are “halfway into decoding the mental processes of a person,” he said.

Companies’ solicitation, storage and sale of neural data is an emerging trend, but the practice is growing quickly and privacy and discrimination concerns abound, said Calli Schroeder, global privacy counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. She is working with the United Kingdom’s data privacy regulator, the Information Commissioner’s Office, to help it develop guidance to companies on the issue.

Through that work, Schroeder has spoken with some neuroscientists who believe neural data can be as individually identifiable as a fingerprint, she said.

The lack of federal neural data privacy laws for non-medical use of the data — medical applications are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and are covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA — means there is nothing stopping companies from creating databases populated with brain scans from millions of consumers.

This information could be used to discriminate against individuals who are neurodivergent or mentally ill, Schroeder said.

She foresees a future in which brain scans also could be used to determine who to target advertising to or dictate employment and money lending decisions.

“There are uses of this that we worry about and the way that this is shared that we worry about,” Schroeder said. “There is high risk.”

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering digital privacy, surveillance technologies and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.