NATO allies’ new cyber pledges to remain classified — but here’s what we know

During this week’s NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, allies agreed to a number of new cybersecurity pledges. The substance of these commitments has not been detailed — the documents themselves are classified — but here’s what we do know.

The official text of the Vilnius Summit Communiqué restates the position of the alliance’s Strategic Concept (2022) that “cyberspace is contested at all times” and is not just a concern for NATO during the circumstances of an international armed conflict.

It repeats NATO’s established doctrine that a “cumulative set of malicious cyber activities could reach the level of armed attack and could lead the North Atlantic Council to invoke Article 5,” the keystone commitment that an attack against one ally shall be considered an attack against all.

But the communiqué also announces new ground.

“Today, we endorse a new concept to enhance the contribution of cyber defense to our overall deterrence and defence posture. It will further integrate NATO’s three cyber defence levels — political, military, and technical — ensuring civil-military cooperation at all times through peacetime, crisis, and conflict, as well as engagement with the private sector, as appropriate. Doing so will enhance our shared situational awareness.”

Allied delegates to Vilnius all endorsed this concept, as set out in a paper with the catchy title of: “Concept for enhancing the longer term contribution of cyber to NATO’s overall deterrence and defence posture.” What exactly they were endorsing isn’t completely clear — the paper itself is classified.

When the concept was announced earlier this year by David van Weel, NATO’s assistant secretary general for emerging security challenges, he explained it set out a greater role for military cyber defenders during peacetime, alongside mechanisms to integrate private sector capabilities within allies’ national defensive capabilities.

Van Weel had previously spoken to Recorded Future News at the Munich Security Conference, when he praised the “unique” work that companies like Microsoft and Google had been doing in Ukraine, and said the alliance needed to consider a more structural cooperation with the private sector.

The new concept also attempts to drive allies to adjust their cyber defense posture, becoming more proactive and assertive in response to state-sponsored attacks: “We need to move beyond naming and shaming bad actors in response to isolated cyber incidents,” as van Weel said.

The communiqué states: “We are determined to employ the full range of capabilities in order to deter, defend against and counter the full spectrum of cyber threats, including by considering collective responses.”

In a recent interview with Recorded Future News, Christian-Marc Lifländer, the head of NATO's cyber and hybrid policy section, said he felt the alliance needed to do more to impose costs on adversaries who were carrying out cyberattacks, and partially attributed the rising volume of attacks to a failure to impose costs.

“We have to do more,” Lifländer said, and warned “many of the actors have become quite skilled at operating below the threshold of the use of force. Many have become quite skilled in designing their activities around deterrents,” thus driving the need for more focus on what allies’ deterrence actually means.

Also announced in the communiqué was an update to the Cyber Defence Pledge, an existing tool “which allies have decided to revamp,” as Lifländer explained.

“Today we restate and enhance our Cyber Defence Pledge and have committed to ambitious new national goals to further strengthen our national cyber defences as a matter of priority, including critical infrastructures.”

“What we're looking at is no longer something that is just delegated to allies to implement, but is now a tool which for the first time includes national goals, almost minimum requirements, things that everybody needs to have,” Lifländer said.

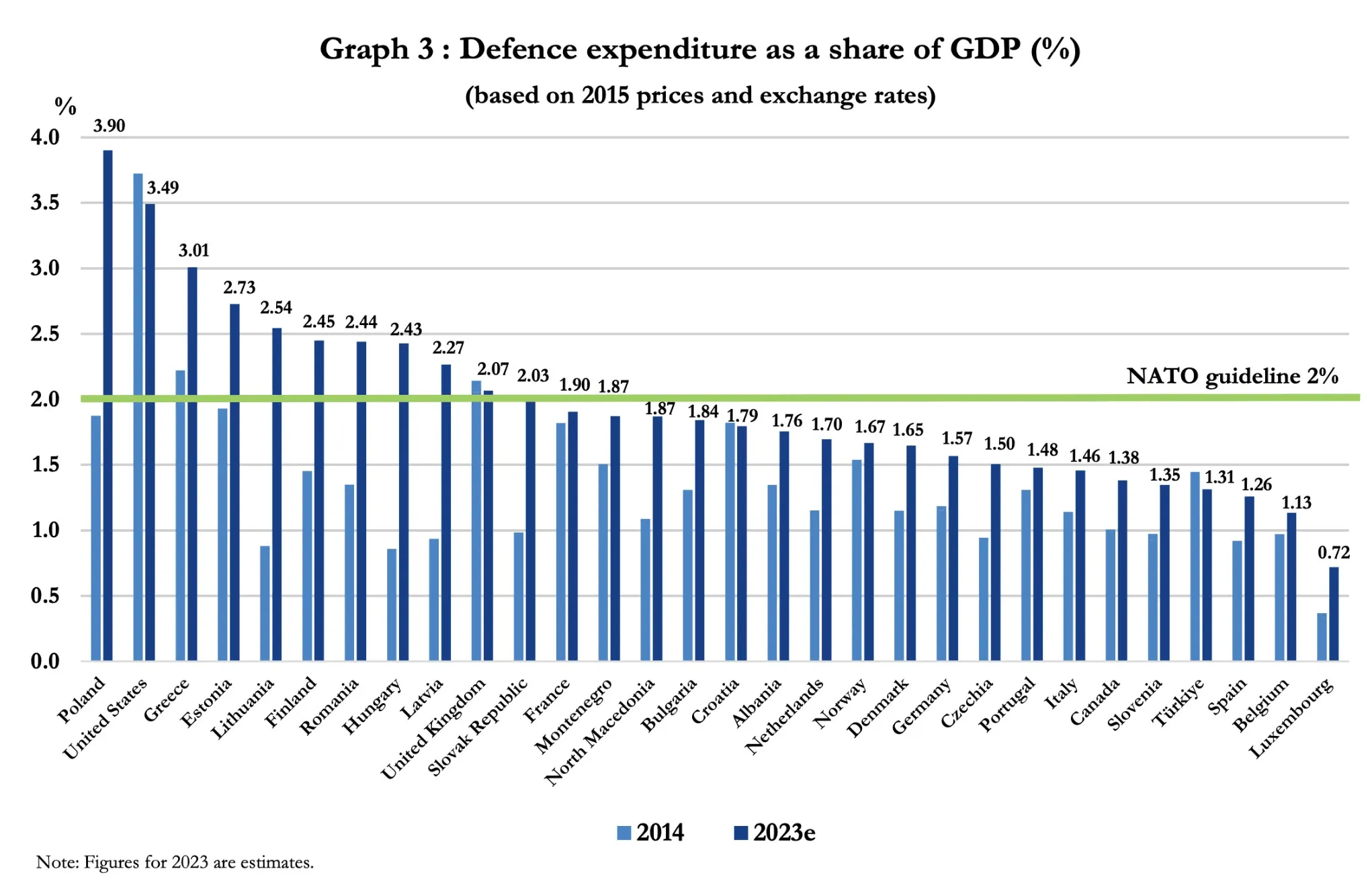

The nature of those national goals has also been classified. Similar to the obligation for defense expenditure to meet 2% of an ally’s GDP — they are likely to receive some domestic political pushback from NATO members, more than half of whom are not expected to meet the target in 2023, including G7 members France, Germany and Italy.

The low level of contributions made by European NATO members to the alliance’s total defense expenditure has often provoked grievances in the United States. Partly motivating the Cyber Defence Pledge is NATO attempting to encourage allies to meet their obligations under Article 3 of the Washington Treaty, which stresses each member’s responsibility to also be capable of defending themselves, as part of the alliance’s collective security.

During the summit in Vilnius, Albania's prime minister Edi Rama said his country needed more funding from the United States to protect itself from cyberattacks, and complained that Congress was “not being fully supportive” in providing his country with more money.

Albania had reportedly considered invoking NATO’s Article 5 in response to Iranian cyberattacks last year which disrupted a number of critical government services. The response involved the U.S. military deploying a team of two dozen personnel on a “hunt forward” operation to assist the Albanians in uncovering adversary activity in their networks, as well as the Biden administration sanctioning Iran’s spy agency.

Although it had been formulated before the attacks on Albania — being mentioned in the declaration from the Brussels summit following the invasion of Ukraine — the communiqué also announced the launch of a NATO-wide cyber incident response capability.

“We have launched NATO’s new Virtual Cyber Incident Support Capability (VCISC) to support national mitigation efforts in response to significant malicious cyber activities. This provides Allies with an additional tool for assistance.”

The launch of VCISC follows the declaration at last year’s summit in Madrid that “Allies have decided, on a voluntary basis and using national assets, to build and exercise a virtual rapid response cyber capability to respond to significant malicious cyber activities.”

As Lifländer explained, if the Cyber Defence Pledge was “left of the bang — by which I mean all of the things that need to happen before incidents take place — then VCISC really looks to the right of the bang. If and when the incident has taken place, how can we be useful in helping a stricken ally to recover and mitigate the malicious cyber activity that is happening?”

The communiqué also confirmed that NATO would hold its first comprehensive cyber defense conference in Berlin this November, “bringing together decision-makers across the political, military, and technical levels.”

According to Lifländer, the alliance’s work on “a better way to react, a better way to shape cyberspace” isn’t expected to deliver results “until next year's summit in Washington.”

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and is also a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative.