Microsoft disrupts Russia-linked hacking group targeting defense and intelligence orgs

Microsoft on Monday published new details about a suspected Russian hacking group that has carried out cyberespionage attacks against government organizations, think tanks, and defense contractors in NATO countries since at least 2017.

Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) also said it has “taken actions to disrupt campaigns” launched by the group, which they call SEABORGIUM but is also referred to as Callisto, COLDRIVER and TA446 by other security researchers.

The group has been highly active this year, with researchers at Microsoft observing campaigns targeting over 30 organizations “in addition to personal accounts of people of interest.”

In July, researchers at Google said they observed the group using Gmail accounts to send phishing messages to government and defense officials, politicians, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks, and journalists. In May, Reuters reported that the group was behind a hack-and-leak operation that tried to build a narrative around high-level Brexit proponents planning a coup.

Microsoft on Monday said it was able to independently link SEABORGIUM to the campaign, adding that the group was also behind a May 2021 information operation that involved documents allegedly stolen from an unnamed U.K. political organization. Researchers added that the 2021 operation did not get picked up or amplified by social media accounts that weren’t tied to the group.

In addition to the U.K., SEABORGIUM “primarily targets NATO countries,” as well as “occasional targeting of other countries in the Baltics, the Nordics, and Eastern Europe,” researchers said. The group was also observed targeting Ukraine’s government in the months leading up to Russia’s invasion, but Microsoft said Ukraine is likely not a primary focus for the group.

In addition to think tanks, NGOs, and defense and intelligence organizations, the group has been observed targeting experts in Russian affairs, Russian citizens abroad and former intelligence officials, the researchers said.

Method of attack

Microsoft said the group conducts extensive reconnaissance of its targets before launching a hacking campaign, and creates various accounts and social media profiles to identify people “in the targets’ distant social network or sphere of influence.”

Fraudulent profiles on LinkedIn — which is owned by Microsoft — were created by the group to spy on employees from specific organizations of interest, the researchers said.

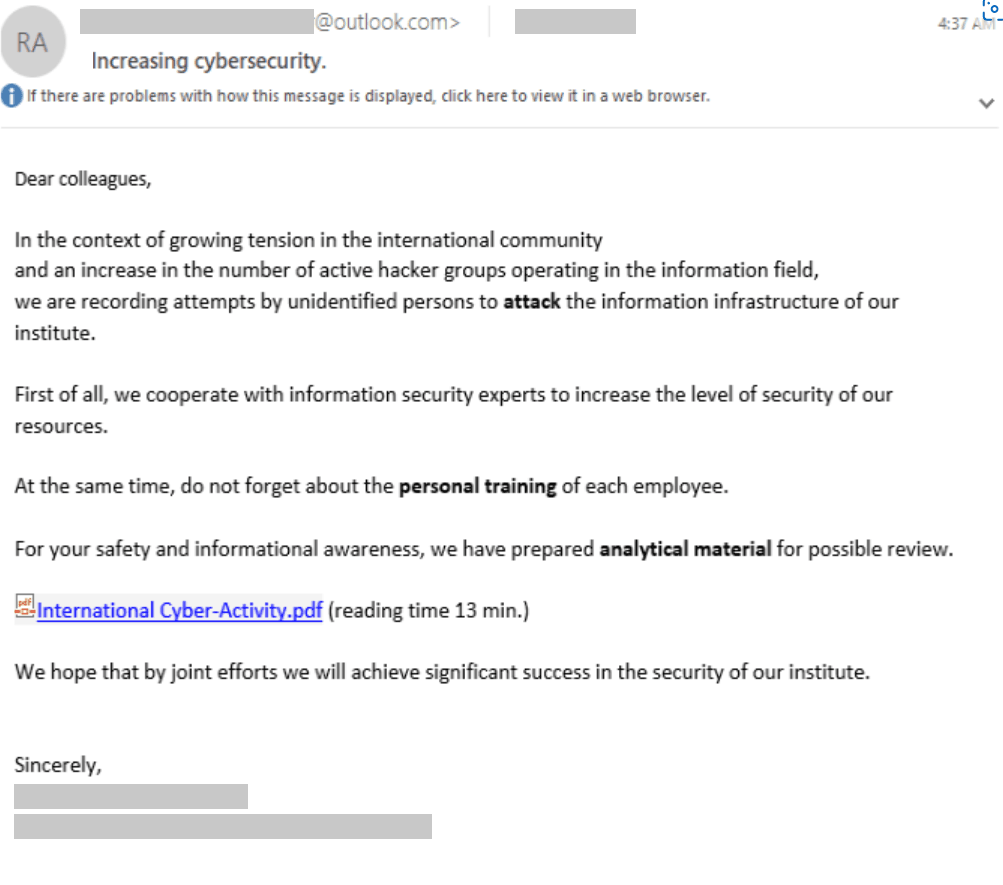

Once the group has conducted its reconnaissance and created accounts to be used in phishing attacks, it generally emails the target with a “benign” message “typically exchanging pleasantries before referencing a non-existent attachment while highlighting a topic of interest to the target.”

“It’s likely that this additional step helps the actor establish rapport and avoid suspicion, resulting in further interaction,” the researchers wrote. “If the target replies, SEABORGIUM proceeds to send a weaponized email.”

Although there are several ways that the group gains access to a target’s infrastructure, the simplest variation involves a URL that directs the target to a server hosting EvilGinx or another phishing framework. The framework mirrors the sign-in page of a legitimate service, and harvests credentials that the target enters.

Microsoft said it has helped customers respond to intrusions that involved exfiltration of intelligence data, the setup of persistent data collection from email accounts and mailing lists, and obtaining access to people of interest.

“There have been several cases where SEABORGIUM has been observed using their impersonation accounts to facilitate dialog with specific people of interest and, as a result, were included in conversations, sometimes unwittingly, involving multiple parties,” the researchers said. “The nature of the conversations identified during investigations by Microsoft demonstrates potentially sensitive information being shared that could provide intelligence value.”

Adam Janofsky

is the founding editor-in-chief of The Record from Recorded Future News. He previously was the cybersecurity and privacy reporter for Protocol, and prior to that covered cybersecurity, AI, and other emerging technology for The Wall Street Journal.