Meta, Twitter took down accounts engaging in pro-U.S. covert influence campaigns

Meta and Twitter have taken down accounts in recent weeks connected to a years-long, pro-Western covert influence network originating in the U.S. that targeted the Middle East and Central Asia, according to a new report from the Stanford Internet Observatory and data analysis firm Graphika.

The social media firms determined in July and August that the accounts engaged in coordinated inauthentic or spam behavior that violated their policies, then shared data about the accounts with the researchers. The Stanford and Graphika report tracks networks of online activity from that data across Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and five other online platforms.

Rather than one single campaign, the data provided by the companies showed a series of overlapping efforts that used deceptive tactics, including computer generated profile images and fake news outlets, to promote an agenda aligned with Western policy priorities and opposing Iran, China and Russia.

“The accounts heavily criticized Russia in particular for the deaths of innocent civilians and other atrocities its soldiers committed in pursuit of the Kremlin’s ‘imperial ambitions’ following its invasion of Ukraine in February this year,” according to the report.

“To promote this and other narratives, the accounts sometimes shared news articles from U.S. government-funded media outlets, such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and links to websites sponsored by the U.S. military,” researchers added.

Data shared by Meta identified the accounts as originating in the U.S., and Twitter said the “presumptive country of origin” of accounts was Great Britain and the U.S., although neither attributed the campaign to a specific actor, according to the report.

Twitter shared nearly 300,000 tweets from 146 accounts sent between March 2012 and February 2022 with the researchers, who found the data could be divided into two categories: those associated with a known U.S. influence operation called the Trans-Regional Web Initiative, and others — which the report focused on — that represented a “series of covert campaigns of unclear origin.” There were 74 Twitter accounts associated with the latter group, according to Stanford Internet Observatory research scholar Shelby Grossman.

Those covert campaigns were also present in data from Meta, which included 26 Instagram accounts as well as 39 Facebook profiles, 16 pages and two groups active between 2017 and July 2022, according to the research.

Meta confirmed to The Record that it removed a network of accounts engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior originating within the U.S. and that it had shared information about the operation with research organizations. Twitter did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the report.

A new subject for study following a familiar playbook

Previous academic research exploring covert influence online has largely focused on authoritarian regimes — including in the same countries targeted by covert campaigns covered in the report.

“We believe this activity represents the most extensive case of covert pro-Western [influence operations] on social media to be reviewed and analyzed by open-source researchers to date,” the researchers wrote.

However, the pro-Western campaign used many of the same strategies as previously studied online influence efforts.

“The assets identified by Twitter and Meta created fake personas with GAN-generated faces, posed as independent media outlets, leveraged memes and short-form videos, attempted to start hashtag campaigns, and launched online petitions: all tactics observed in past operations by other actors,” according to the report.

The researchers broke the network down into four groups based on their apparent target audiences: Afghanistan, Central Asia, Middle East, and Iran.

The part of the network appearing to engage in covert influence activities related to Afghanistan was the longest running, with some Twitter accounts posting as early as 2017 and group activity peaking “during periods of strategic importance for the U.S.,” including the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

The group of accounts targeting Central Asia was the most active, “peaking at almost 200 a day in the months leading up to and immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February this year,” per the report.

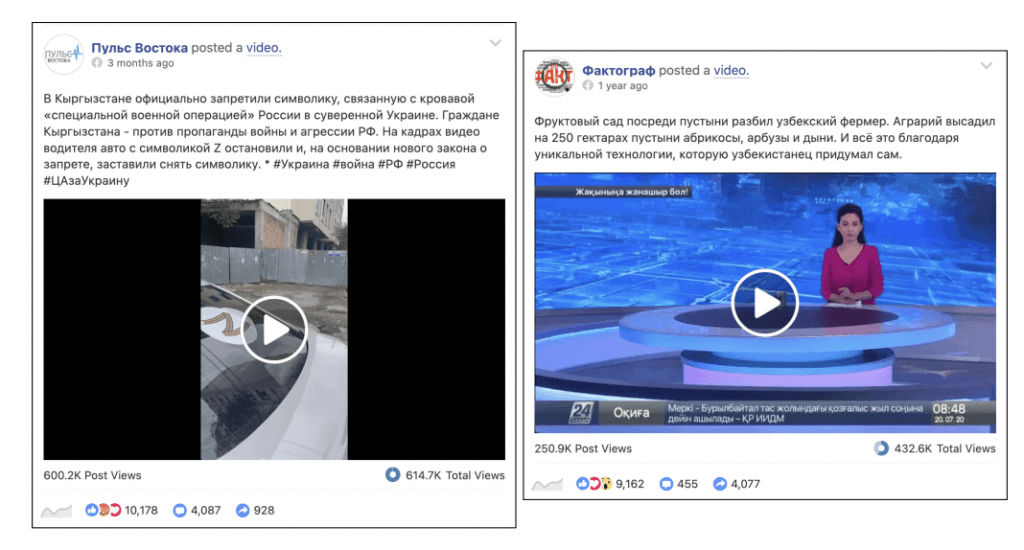

That group included 10 Facebook pages, 15 Facebook profiles, 10 Instagram accounts, and 12 Twitter accounts created between June 2020 and March 2022. They posted almost entirely in Russian, but gained “little traction” on social media for most posts — with the exception of “two viral videos that received hundreds of thousands of views on Facebook.”

One of the videos was about a man in Kyrgyzstan forced to remove a sign supporting Russian forces from his vehicle, and the other was about “an Uzbek farmer growing apricots and watermelons in the desert,” per the report.

The researchers believe that the Central Asian accounts likely “inauthentically” acquired followers at the start to appear more legitimate, possibly by purchasing them. The quality of content on the accounts was also often questionable. One sham news outlet identified in the report, for example, included poorly translated versions of articles or minorly tweaked stories from legitimate pro-Western news sources.

Social media has long been known as a vector for influence campaigns, including Russian efforts targeting the 2016 and subsequent U.S. elections. Social media firms have increasingly worked to reassure the public that they take such activity seriously.

Meta, for example, has regularly provided updates about actions against such campaigns across the world — some including governments appearing to target domestic audiences and others appearing to attempt to influence international affairs.

Although the report shines a light on a different aspect of covert influence campaigns, it also highlights the limitations of known tactics.

According to the research, the “vast majority of posts and tweets” researchers reviewed received only a handful of likes or retweets and just 19% of the accounts had more than 1,000 followers.

“We were able to analyze engagement data which found the average tweet received just 0.49 likes and 0.02 retweets,“ Grossman told The Record.

Andrea Peterson

(they/them) is a longtime cybersecurity journalist who cut their teeth covering technology policy at ThinkProgress (RIP) and The Washington Post before doing deep-dive public records investigations at the Project on Government Oversight and American Oversight.