As major elections loom, Meta unveils its internal Online Operations Kill Chain

Next year will feature some of the most geopolitically significant elections of our times. Voters will be heading to the ballot boxes in not only the United Kingdom, United States and European Union, but also India, Turkey and Taiwan.

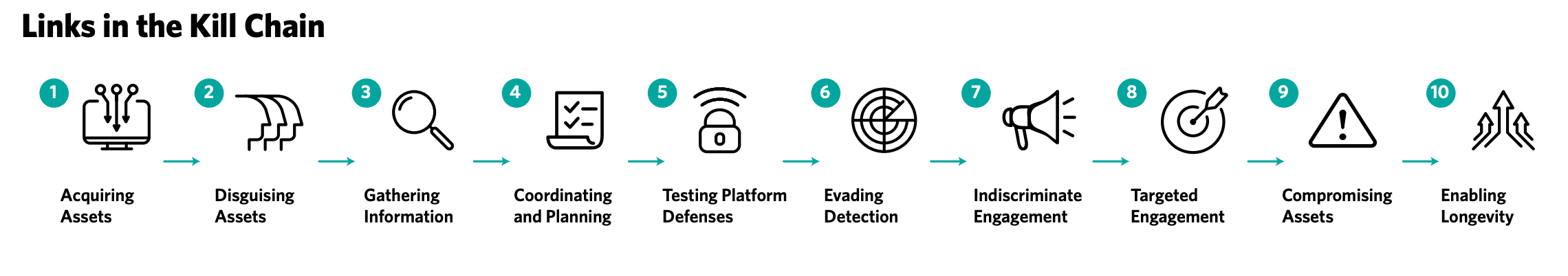

Anticipating an even greater need for “investigative teams across industry, civil society, and government” to collaborate against online interference in these elections, Meta published on Thursday a new Online Operations Kill Chain framework for analyzing and responding to these threats.

The framework is a tool used internally at Meta to formally “analyze individual operations and identify the earliest moments at which they can be detected and disrupted.” The parent company of Facebook and Instagram hopes it will help other defenders detect and disrupt operations when they see them on their networks, too, and help everybody share their findings.

The Record spoke about the new model to two of the company’s leading security experts, Ben Nimmo, Meta’s global threat intelligence lead, and Eric Hutchins, a Security Engineer Investigator on the influence operations team.

Nimmo previously helped expose foreign election interference in the United States, United Kingdom, and France. Hutchins, who previously worked at Lockheed Martin, invented the Intrusions Kill Chain model based on the military concept of a “kill chain,” which formally describes the separate phases of an attack, from identifying a target through to its destruction.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

The Record: How did the Online Operations Kill Chain come about?

Ben Nimmo: For me, this really started a couple of years back when I joined Meta. I’d come from the influence operation (IO) space and in the IO space we'd already been seeing some pretty big trends and shifts. We’d seen threat actors were moving more and more to small platforms, trying to spread themselves wider and larger over the internet, for example, or there were more and more cases where they were using AI-generated profile pics to try and disguise their accounts.

When I moved to Meta, one of the coolest things about moving was meeting expert investigators from all kinds of other areas: the cyber espionage guys; the fraud team; the team tracking terrorists and dangerous organizations; we'd have these great investigators and investigative nerdy conversations and we'd have moments of saying ‘Hang on, your bad guys do that too?’

And the more we talked it through, the more we realized, no matter how diverse the operations were, there were these real commonalities between them. Starting from the real basics: If you want to do an online operation, you've got to get online and there's only a certain finite number of ways that you can do that. And so we started thinking about, can we use those commonalities as a map? Can we map the paths that threat actors take? Can we map out each step on the path? Because if we can do that, we can work out where we can trip them up.

So we started thinking through these commonalities, thinking through the map. And we were working through that process when Hutch [Eric Hutchins] joined and kind of put rocket boosters under the whole thing. As Hutch's background was both cyber and kill chains, he was the perfect guy in the right place at the right time.

The Record: How did you come up with the Intrusion Kill Chain and why?

Eric Hutchins: When I first started at Lockheed Martin, I very much felt like I was at the right place at the right time to see the earliest days of APTs [Advanced Persistent Threats] before it was even a thing, before it was even an ‘A’, and lacking any sort of tool to analyze that threat — that language didn't exist. And so my teammates and I, the genesis of the Intrusion Kill Chain was born out of that necessity to respond to those types of threats. [At the time] the best practices for how to respond to an incident were all defender-oriented. They were about the steps that you were supposed to take. Your job is to identify, your job is to detect, and your job is to contain and eradicate the threats. But that doesn't tell you when your detection job is done. It doesn't tell you when your containment job is done. You need a whole different way to show 'Have I completed my analysis? When am I done?' And it was a realization that you're done when you understand what the adversary did and you [can] recreate what they did. And so rather than have a process that's about the steps I take, we came up with a process about the steps that they took. And whether I am investigating it starting at step seven, and I have to work my way back, or I start at three and I go backwards and forwards, it doesn't matter where I start — I have to recreate their timeline. So that was the real inspiration, was flipping it around. And then with that understanding, that can then drive our actions. How do we detect this? Here's the tech that they're using, how do we respond to it? …Those were the circumstances which really sparked it.

Where it took off was when we started using it as a community. When we started sharing, when we started reporting and collaborating amongst our peers and saying, Here's what I'm seeing, here’s this IoC [indicator of compromise]. And initially, it was just ‘here's all the IOCs,’ they're sitting in a list, but it tells you something differently if that infrastructure was used for reconnaissance against you versus if it was used for exfiltration. You insert your data in a very different way with just that little bit of context. So once it [the Intrusion Kill Chain framework] started taking off, from collaboration, it became this common language. And I think that's when it went from an idea that was helpful amongst a team to an idea that was changing how a community talks.

The Record: How does the kill chain concept apply to information operations?

Hutchins: Coming into the IO space, [meant bringing in] that mindset of thinking about how to understand the operation end-to-end, how do we drive the completeness of our analysis to ensure that we're understanding every step of the operation, how do we push our detections earlier in the operation rather than later? And fundamentally observing how adversaries shift and change over time and evolve our defenses to keep pace. As Ben mentioned, it was that realization that these similarities across so many different types of harms, gave us this inspiration to generalize this into online operations. This is bigger than any one individual harm type, but in the nature of how to conduct an operation online that we see these commonalities.

The Record: How broad a range of activities does the framework cover?

Hutchins: What we're trying to do here is provide a new baseline across these different archetypes, [that is] something that hasn't been done before, we’re trying to fill a space where that hasn't existed yet. Second, we are focused on online operations, principally those that are meant to be seen. That is a really important distinction. These are operations that are supposed to be in front of people's eyeballs, as opposed to an intrusion that is compromising a VPN appliance that's not designed to be seen by anybody. So there is a distinction of applicability that these are operations that are meant to influence humans. That's the ultimate target of these operations. So that is different [but] there are still similarities, I think, referring to the nature of how operators acquire and manage their network infrastructure. I think there's been a real shift in the APT space over the last few years in the complexity of their networks, [that] is really important. And that's something that we see as well in the IO space of how they get on to the internet, how they interact with our platforms and other social media platforms, [it] is increasingly complex, and [there are] multiple layers of deception in there.

The Record: How does it help foster collaboration through the community?

Nimmo: One of our goals right from the start, which flowed from the way this idea came up, was, let's break the silos, let's actually create this kind of common baseline where it doesn't matter if you're a cyber investigator, or an IO investigator, or you're working on frauds and scams, we can create that common language and have a common roadmap of 'here are the steps that an operation goes through'. And interestingly, to Hutch's point, once we kind of got our ideas more or less lined up, we went through this whole series of peer consultation processes. So we talked with investigators, we got feedback from investigators at other platforms and OSINT teams. And that helped us refine it and make it more precise. But there were two things that really came up there. One was that there are words that you think are common, and everybody understands. And you realize that actually, yeah everybody understands them, but they don't understand them the same way. So for example, ‘persistence’ means a very different thing if you're talking about somebody who keeps on posting messages [versus] somebody who is creating malware which is going to linger on a computer, right? And so there was a need for a shared understanding of the vocabulary.

And then the second point is that there are many different words for the same thing. So different folks talk about disinfo, or misinfo, or malinformation, or dis/misinformation or influence operations. Sometimes they mean the same thing. Sometimes they mean variations on a theme. And so we started out with this idea of a map, right? Can we chart the steps they go through? But as we were going, we realized we really needed two things. You need the map, and then you need the dictionary. It's like visiting a foreign country, the map tells you what are the steps they go through, but the dictionary tells you, here's how I can explain to other people what I'm seeing. And so it's having that baseline, which goes across many different problem areas, is what we think is kind of the unique addition to this space, and is certainly what we're hoping to achieve.

The Record: How does Meta use it internally?

Nimmo: Across the different investigative teams, we use it ultimately to shape and frame our own thinking and our understanding. The thing we found is that there are many ways that the kill chain is useful. You can use it to think, OK, these are the steps that an operation is going through, how many different steps could we interrupt and disrupt them [and thus] ‘complete the kill chain’. You can use it to compare two different operations. So you could compare an espionage op and an influence op and a scam, or with some of the long-running operations that are out there, you could actually compare the same operation at different points in time and say, ‘Oh, now we're seeing a new behavior,’ right?

As investigators and as the guys who are doing this hands-on, certainly for me as much as anything, it's a mental model, which makes me think, am I looking at this operation … Am I missing things? So whatever operation I'll be working on, I'll be thinking, OK, at the back of my mind, acquiring assets — am I confident I know how this operation is acquiring its assets? How is it setting them up? How is it disguising them? You know, are they stealing profile pics? Are they using GAN [Generative Adversarial Networks] faces? How are they trying to engage people? Are they just scatter-shooting it to the wind or are they actually targeting, are they tweeting it with very specific @ mentions? But by going through the links in the chain, it kind of brings that mental discipline of understanding here's what I'm actually seeing. And as you start to record your observations from each operation, you can build up a patternable behavior that goes across many operations.

The first time I ever observed that as an open-source researcher was back in 2019, there was a big takedown that Meta did from, I think it was TheBL, where I was at Graphika. And we did this big write up on what we called Operation FFS, which clearly stands for ‘Fake Face Swarm’. It was the first time we've seen in the wild so many GAN faces. And then over time, you see that in more and more places, clearly, more and more threat actors have discovered that GAN faces are a thing. And presumably they think if I use one of those, rather than stealing somebody else's photo, I won't be vulnerable to reverse-search in the same way.

So then you start seeing not just in the influence ops space, but maybe in the scams or in sort of social engineering, espionage, the same type of pictures are showing up. And so you can really start to compare across different spaces. Different investigators can get together and say, 'Hey, are we seeing the same thing?' And from that you can work out how you teach people to identify it, what are the clues that you would look for.

And so what we're doing at Meta is that combination of using it to make sure we're thinking through all the steps, and also using it to kind of to make sure that we're breaking down our own silos, and getting these collective insights where any investigator on any team can work out. 'Alright, this thing I'm seeing, is it a one-off? Is it the first time any of us have seen this? Or is it actually popping up in five different threat areas at the same time?’

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative, now Virtual Routes. He can be reached securely using Signal on: AlexanderMartin.79