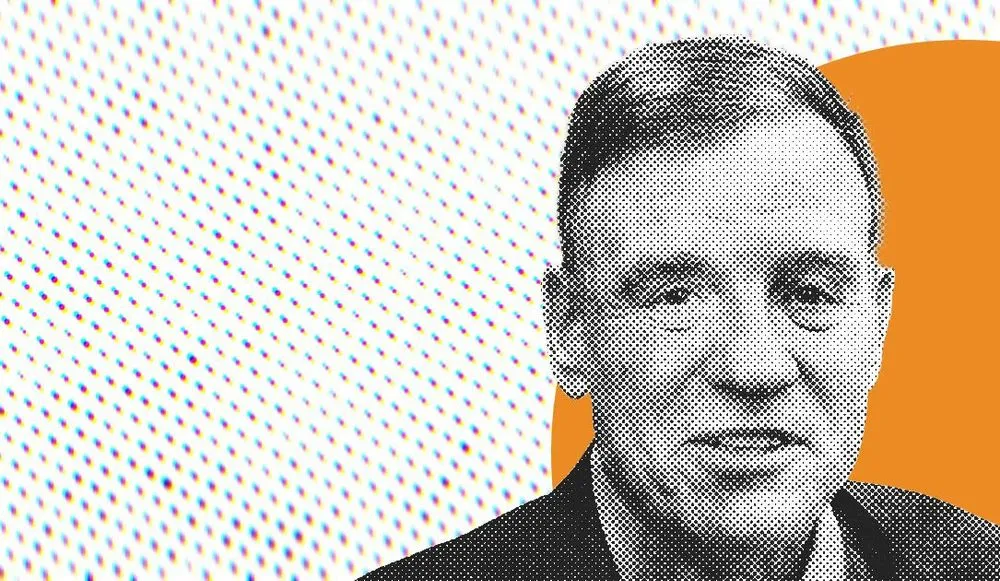

Sen. Mark Warner hopes ‘a little bit of name-and-shame’ will make tech execs ‘up their game’ ahead of the election

Some fifty days from the November presidential contest, Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) says people still aren’t taking election security seriously enough.

Back in the spring, to much fanfare, he told anyone who would listen that election interference will be a bigger problem in 2024 than it was in 2020. “Well, I said that a number of months ago mostly to be provocative,” Warner said in an interview in his Senate office earlier this week. “I was trying to push the United States government to lean in more, and I think generally they have.”

But he says there is still much to do. And that’s one of the reasons, he said, that he asked executives from Meta, Alphabet and Microsoft to testify before the Senate Intelligence Committee Wednesday on disinformation and misinformation ahead of the election.

“We have seen all of these companies take down or cut back fairly dramatically most of their own self-policing activities,” he told the Click Here podcast in an interview. “Frankly… my hope is a little bit of name-and-shame here may have them up their game.”

And it seems to have worked, at least a little bit.

A day before the hearing, Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp said it would ban Russian state-owned media accounts — including RT — from its social media platforms in response to its influence operations.

Hours later, Microsoft published a new report warning that two Russian-backed groups have used X (formerly Twitter), Telegram and several fake news websites to disseminate fictitious videos about Vice President Kamala Harris. One video claimed Harris had been involved in a hit-and-run and another said her supporters attacked a Donald Trump fan.

The interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Click Here: Can you talk about how the landscape of election interference has changed over the past four years?

SEN. MARK WARNER: Initially it was just Russia, it is now Russia, it is Iran. China is still trying to figure out what to do, what they want to do. And even some frenemy nations have tried to influence our elections.

Secondly, you know, unfortunately as we've seen recently about fake stories about immigrants eating pets, Americans have just a much greater tendency to believe crazy things.

And then finally, we've got all of these new artificial intelligence tools, deepfakes being one example, but a whole host that allows you to spread disinformation, misinformation at speed and scale that's unprecedented. So I said [we’re less prepared for election interference in 2024 than 2020], I put those words out and I think we got people's attention. We just won't know though how successful we are probably until late in the election because generally speaking, foreign entities will launch their efforts quite close to the actual voting date.

CH: There could be an October surprise we aren’t expecting.

MW: Right. At the Munich Security Conference this year, because I was concerned that AI tools might disrupt elections all over the world, 20 companies, including TikTok and X, all signed onto a voluntary set of agreements about being proactively willing to take down AI manipulation around elections. I've been concerned that they have not been as proactive. That's the bad news.

The good news is we've not seen artificial intelligence tools used in the European parliamentary elections, the British elections, the French elections at the level that I was afraid of. So a little good news, bad news. So I want to press them in particular on AI. But I also want to garner attention on that for the public. So if they see something that doesn't feel right or smell right or somebody saying, ‘No, you don't need to vote on this day. You vote on that day,’ that the public would be aware that this very well may be foreign malign influence in our elections.

CH: So is this just to shed some light on the problem, or are you hoping that tech companies will come out and say, we're specifically doing this, or we're specifically doing that?

MW: Well, we have seen all of these companies take down or cut back fairly dramatically most of their own self-policing activities. Frankly, Twitter/X, when Mr. Musk took over, almost eliminated that. We have, unfortunately, seen Meta and Google and others cut back as well.

CH: Do you feel the naming and shaming actually works? Not just for tech companies specifically, but the practice more generally when, for example, the DOJ brings indictments against PLA hackers or people at RT who are allegedly launching influence operations… Does it work or just ends up raising general awareness?

MW: If I had my druthers, I would vote. I think Congress should legislate here. I think it's long overdue on reform of what's called Section 230 [of the 1996 Communications Decency Act], which is basically a get-out-of-jail-free card for any of these social media companies for anything that happens on their platform.

Our record of legislating guardrails on social media or on AI is pretty poor, it’s virtually nonexistent. So I think it is both. Will they voluntarily up their game? And can we keep the public informed that other nation states may have a preference on a candidate or they may just simply want to undermine other states or basic faith in our systems. Unfortunately, when you have at least one presidential candidate that constantly seems to come back to this theme that you can't even trust our elections, that does not do our system any favors.

We have made progress. I mean, when I think about this issue, there's one side, which is the actual machinery of elections, the integrity of the voting systems and the reporting systems. And I think we've made great improvements there. CISA has made great progress. But again, we have to be wary because there could be other types of AI-related attacks.

CH: When the Justice Department announced the RT case earlier this month, one of the things that caught my eye was that RT allegedly has a cyber espionage cell. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

MW: I'm still getting more of the background on that, but what we've seen with RT, you know, I don’t think they pretend to be a news organization anymore. The Russians have very good cyber capabilities in many ways. I've been surprised that we've not seen, for example, in Ukraine, even greater use of Russian cyber.

In the past as well, what would happen? The Russians would have to create a fake persona and then amplify that. Now we've got Americans saying crazy enough stuff on their own. And they, in the case of RT, would amplify that. And in this circumstance some of these far right commentators were helping them amplify their destructive messages and oftentimes mimicking or echoing Russian propaganda talking points – that's a real problem.

CH: So about the cyber espionage unit itself, do we know what they were doing or are we still finding out?

MW: I have not gotten a brief on that yet. In the last 10 days, I think we are still finding out, but let me follow up on that one.

CH: Back in June, the Supreme Court rejected a Republican challenge aimed at preventing the government from contacting social media platforms when they found disinformation or misinformation posted. The High Court basically said that the people who brought the case hadn’t suffered the sort of direct injury that gave them standing to sue. So now the communication between, say, the Biden administration and those companies can talk again. Are you seeing a difference since that was resolved?

MW: The short answer is yes. The case gave us about an eight month window without communications. Part of that, even when you turn the green light back on, you've got to know the person on the other end of the line. You've got to have some protocols that take some time to work through. The good news is that here we are now, you know, roughly 50 days away from the election. I think those communication channels have been reestablished.

CH: But they must be a little gun shy, if you look at something like the Stanford Internet Observatory which was in the crosshairs of someone like House Republican Jim Jordan and ended up shuttering their operations… It must send a shot across the bow.

MW: Absolutely. Matter of fact, the level of independent researchers — similar to the Stanford group, but there are a few others — that have really pulled back because of their concerns about, frankly, being harassed, being sued on a constant basis.

The right wing has targeted some of these individuals and I think that puts a chill on what in many ways has been one of the most valuable tools we have. Independent researchers can point things out in ways the government can’t. And then we can follow up with social media platforms and they say, ‘Well, we don't want to be called out for bad behavior, so we're going to improve our activity.’

It has been very disturbing to me that we’re down to literally only one or two still remaining independent organizations trying to help police this area. And we’re going to talk about that in the hearing too.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”