Lapsus$: The script kiddies are alright

One afternoon last month, the regional head of security for the identity management platform Okta, an Australian named Brett Winterford, was in the middle of a client meeting when his phone sprang to life. “The first message said, ‘It looks like you’re going to have a bad day,’” he recently recalled. “And the second message had the screenshots.”

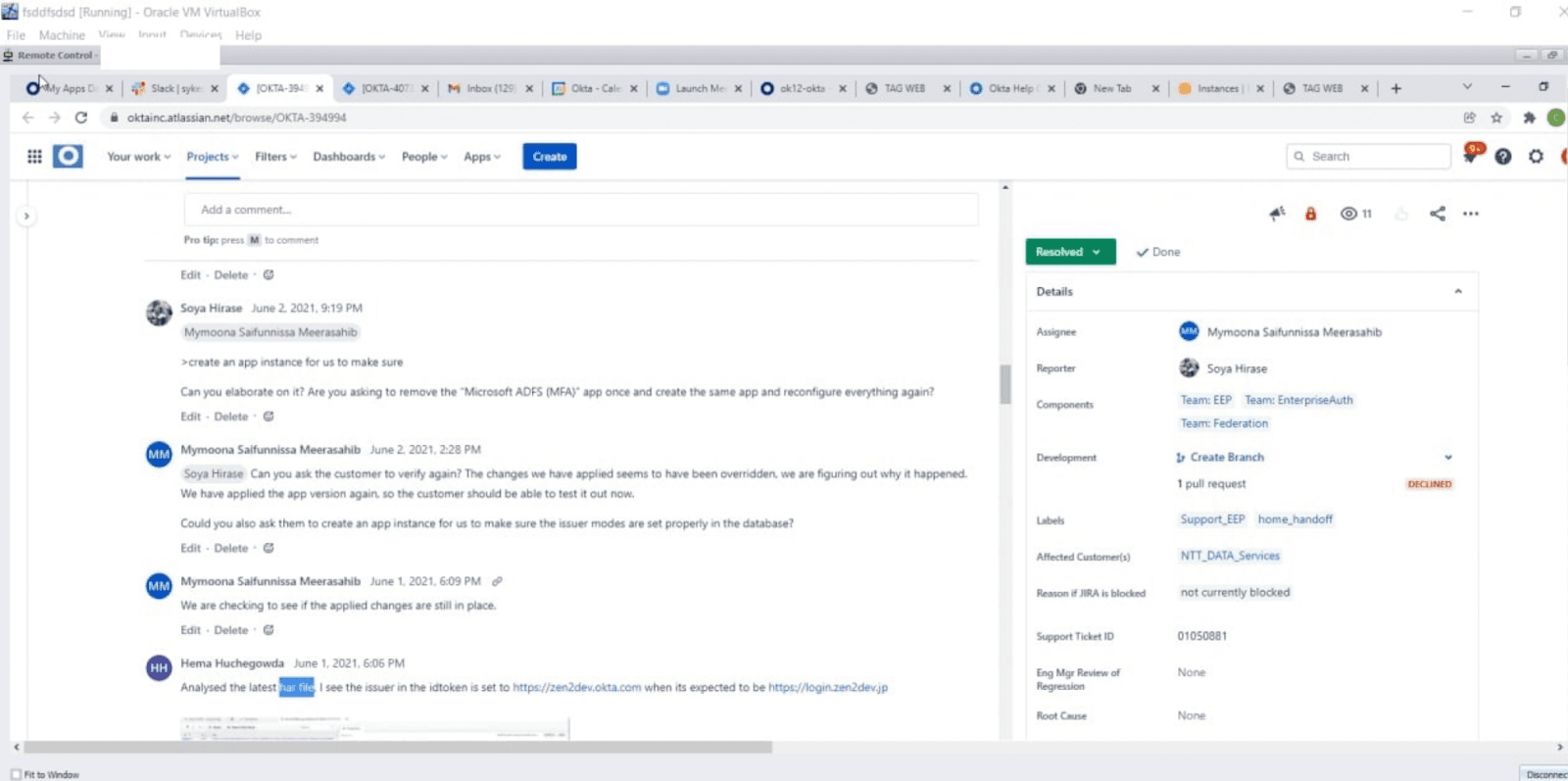

“The screenshots” were pictures that a band of hackers had loaded onto a Telegram channel – an encrypted one-way messaging app that, in their case, has some 60,000 subscribers. The screenshots were annotated with helpful captions that read, among other things, “Photos from our access to Okta.com.”

The Telegram messages suggested that the hackers had cracked into an Okta technical support engineer’s account and now had the ability to change passwords, authenticate accounts and put all of Okta’s customers at risk. The last screenshot ended with a smirking emoji.

When asked if he had managed to control his reaction as he digested this during a client meeting, Winterford laughed and said, “I don’t think I have that good a poker face.”

Okta is headquartered in San Francisco and has some 15,000 customers. It offers single sign-on (or SSO) and multi-factor authentication to companies around the world. Much of the important information we never want hacked is meant to be kept safely behind this kind of security wall and some of the world’s largest companies count on Okta to prevent unauthorized people from breaking into their networks.

Typically, Okta users start by logging into their company website and then are required to pass through a series of authentication tests to prove they are who they say they are. In Okta’s case, the company sends a code or an email that requires a response before authorizing entry into a network. That’s why when screenshots suddenly appeared in a Telegram channel that suggested Okta had been compromised, the tech world gasped.

“From the first moment that these screenshots were published, we had two things in mind. One, figure out exactly what happened from a technical perspective, technical impact,” Winterford said, “and two, get in front of our customers and explain to them what had happened.”

As Winterford and his investigators began to unwind the hack, the breach became both less and more troubling. Less troubling because it appeared to be part of an attack that the Okta team had caught and contained two months earlier, in January 2022; and more troubling because the hackers behind it were known to be an unpredictable, hard-to-control, impulsive lot who seemed strangely unafraid of getting caught: they called themselves Lapsus$.

“Our threat intelligence team at Okta had been monitoring them,” Winterford said, adding, “we viewed them as the kind of adversary that you could come across just because of how prolific they were.”

On Telegram, a hacking group called Lapsus$ posted a series of screenshots that it claims were taken from its access to “Okta.com Superuser/Admin and various other systems.” The post also stated, “BEFORE PEOPLE START ASKING: WE DID NOT ACCESS/STEAL ANY DATABASES FROM OKTA - our focus was ONLY on okta customers.”

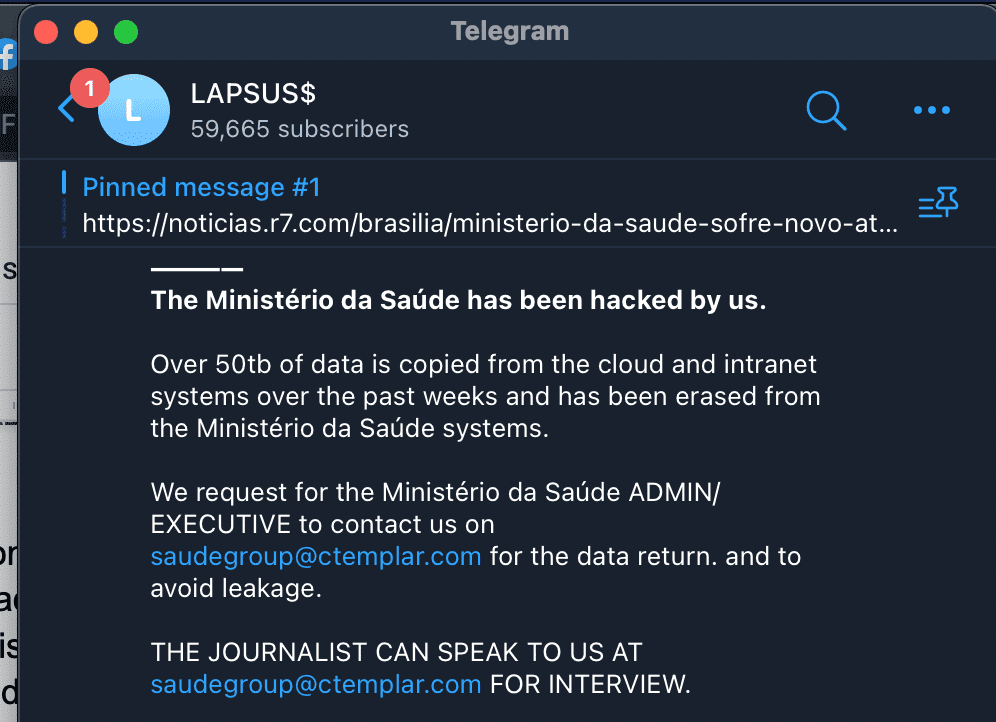

In just a few short months – from December 2021 up until March of this year – Lapsus$ had launched a spectacular number of hacks. They began by targeting Brazil’s Ministry of Health. They stole and then deleted 50 terabytes of COVID-19 data stored on its servers and then posted a message to the Brazilian authorities saying that their internal data had been copied and deleted. "Contact us if you want the data back," the message said, helpfully including email and Telegram contact information.

Lapsus$ used its Telegram channel to boast about hacking the Ministry of Health in Brazil.

That attack, according to the cyber security firm Flashpoint, was followed by 15 more mostly in Latin America and Portugal.

Then in February, the group shifted focus and set its sights on high-tech firms. They began by stealing source code from NVIDIA, the computer chip maker, and then followed that up by targeting consumer electronics giant, Samsung.

“They seemed to be crafty and resourceful and had a lot of time on their hands,” Winterford said. “And, a lot of folks had remarked that it reminded them of these kinds of groups that just almost love hacking for the notoriety more than anything else.”

Saying they had successfully hacked Okta provided exactly that.

Script Kiddies

It isn’t hard to find the person who is the alleged leader of Lapsus$. He’s 17 and lives in the U.K. Because he’s a minor, we’re not using his name. We reached out to him and his parents with a raft of emails, and they didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment on this story.

But even without speaking to them directly, it is relatively easy to find out a lot about a hacker who goes by the screen name White.

Allison Nixon is the chief researcher at a cyber security company called Unit 221B and she’s been tracking White and some of his earlier exploits for quite a while now. She says that even though is just 17, he’s been in the script kiddie hacking world for some time and “his hobbies include re-offending,” she said.

Script kiddies are people who aren’t experts at coding but use other hacking tools – like social engineering – to crack into systems and networks. Traditionally, they haven’t gotten much respect in the hacking world and that may have been, at least in part, what fueled Lapsus$’ hacking spree. They were intent on proving themselves.

Nixon says once she started digging into White’s online profiles, his historical posts and activity, she found accounts that went back years. “When you read the material and look at the dates of when they were posted, the only conclusion you can come to is that this kid has lots of experience in the criminal underground,” she said.

We found people who knew him who agreed to talk to us, but didn’t want to be named or recorded. They were neighbors and local kids who claimed White hacked their bank accounts, took control of their Xbox’s, and demanded money to open them up again.

Apparently, this had been White’s modus operandi as far back as anyone could remember. When his computers were confiscated in the past, they added, White always found a way to get new ones.

"Because of this ego motivation coloring a lot of their actions, it sabotages a lot of their operations."-Allison Nixon, Unit 221b

Nixon says the Lapsus$ crew – which is thought to be less than a dozen people and mostly adolescents – is different from any other hacking group she’s ever followed. For one thing, they don’t depend on malware. They’ve been known to buy malware on the dark web, but more often they use older techniques and good old fashioned social engineering.

“They are old school,” Nixon said. “They are downloading data, deleting it, and then demanding money in exchange for restoring it.”

There are no elegant malware shells or zero day exploits. Instead Lapsus$ appears to be really good at finding gullible people who either click on something they shouldn’t, or can be sweet-talked into providing access to something Lapsus$ should have access to, which presents a huge problem for companies.

Cybersecurity teams can build walls and deploy virus scanners against malicious code, but when the vulnerabilities are carbon units (you know them as human beings), that is much harder to cabin – and is part of the reason for Lapsus$’s relative success.

Case in point, the old-school schemes on which Nixon believes White cut his teeth: something known as SIM swapping. It involves convincing a cell phone carrier to switch an existing phone number over to a SIM card that the scammer has. Sometimes it requires talking to a customer representative. Other times it can include grabbing tablets from a mobile phone retail outlet and making some quick changes.

Once the SIM swap is made, hackers can complete text-based two-factor authentication checks, steal personal information, or trick services into coughing up passwords. Microsoft said as much after it investigated a hack back in March. The company says it traced a number of Lapsus$ hacks back to SIM swaps in which the group took control of an employee’s phone number and text messages so they’d get access to those multi-factor authorization codes.

While that might seem like small ball, hacking companies one individual at a time, Nixon says, has made Lapsus$ appear to be big dog hackers. “The total volume of takeovers is going to be low,” she said. “But the targets they choose are always going to be high profile.” Some estimates say Lapsus$ has already raked in some $14 million from its victims just since December.

What is so crazy about all of this is that the Lapsus$ crew aren’t great hackers in the traditional sense of the word. They aren’t great coders; they are great con artists.

When the investigations team at Okta studied the computer logs from that January hack of the third party vendor, Sykes Sitel, Winterford said it seemed like the group didn’t fully understand what it had cracked into. “They were really just in an experimental mode or a discovery mode, trying to figure out what could, how could they leverage that access in some way,” Winterford said.

They’d try to get into a privileged account in one way… get blocked and then give up and try another. It wasn’t methodical, it was frenetic. “A different kind of adversary might have been more patient and might have performed more discovery,” Winterford said. “These threat actors were very much all about try it out and find out.”

They were a bunch of adolescent hackers who were just out for a joyride, getting an illicit thrill from rattling the cages of high-tech companies.

In fact, those Okta screenshots – the ones that were supposed to ruin Winterford’s day – weren’t exactly what LAPSUS$ claimed they were. They were not inside Okta’s network, as they claimed. They had compromised one service engineer’s account and sat in on client sessions but their access, by design, was very limited.

“This tool [that they broke into] was built with insider threat in mind and had least privileged access,” Winterford said, adding that to change passwords or authenticate users the hackers needed to have access to a target’s email or already be inside their organizations.

But what fun would there be in saying that?

So Lapsus$ did what you’d expect a teenager to do: they took strategic screenshots, wrote some creative captions, and made it look like they had just compromised a giant company. Even though, it appears, they didn’t really.

In an after action report released last week, Okta said only two of its customers were compromised. They wouldn’t reveal who they were aside from saying they were medium-sized companies. Winterford said there was only one session of hacking that included them. It lasted about 25 minutes.

But they could only say that definitively months after those January screenshots were taken and weeks after they appeared in the Telegram channel. The damage was done.

“In a sense, they didn't really need to perform any account takeovers or configuration changes or anything of that nature to have some impact that would make them more notorious,” Winterford said.

Which presents a huge problem: how do you protect your company from what is essentially a hacker disinformation campaign?

While a hacker can swipe source code and hold information for ransom, they also have the power to do something that could be even harder to fix: strike at a company’s reputation.

“There isn’t really a playbook for when a bunch of hackers break into your third party support provider, observe a few client sessions of a technical support engineer, and then take screenshots and publish them on their Telegram channel,” Winterford said. “It's just not a scenario you come up with for a tabletop exercise.”

At the end of March, the City of London Police announced the arrest of seven people in connection with the Lapsus$. A spokesperson for the London police declined to comment on the ongoing investigation, but police did say publicly that the seven are between the ages of 16 and 21. A short time later, Lapsus$ announced in its Telegram channel that some of its members were taking a “vacation.”

Nixon says there’s a lesson here: there is a whole crop of young people who have been dabbling at the edges of the hacking world… and they could be waiting in the wings to strike. “The script kiddies are growing up,” she said, adding that SIM swapping methods are being used for more and more high profile attacks.

As if to underscore the point, Lapsus$ re-emerged at the end of April to announce in its Telegram channel that it had hacked another company: this time it was a software services company called Globant. The group posted a screenshot in its Telegram channel that showed a roster of folder names with brands like Facebook, DHL and C-SPAN.

Sean Powers and Will Jarvis contributed reporting to this story.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that SIM swaps were used in a March hack on Microsoft. The company said it was one of Lapsus$ preferred hacking techniques but did not say it was specifically used in this case — the hack was likely a result of password stealers and stolen credentials purchased on the dark web.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”