Behind the FTC’s plan to hire child psychologists to help regulate social media firms

Alvaro Bedoya, a commissioner at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), is known for his expertise in digital privacy — a skill which is serving him well now as the commission works to better understand the effects of social media, particularly on children.

Bedoya told Recorded Future News in a recent interview that with the strong support of Chair Lina Khan, the FTC plans to expand its ranks of experts by next fall. The agency will bring child psychologists on staff to help inform the commission’s potential rulemaking and enforcement actions related to social media companies. Bedoya recently returned from London where he met with the UK’s top technology company regulators to understand their more aggressive approach in addressing how social media impacts kids.

The founder of the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown University Law Center, Bedoya has long been an important figure in privacy and civil rights research and policy. He previously served as the first chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law.

He told Recorded Future News the FTC prides itself on being more than just a “bunch of civil law enforcement attorneys” and has steadily increased the number of Ph.D. economists and technologists in its ranks, better equipping it to go “head-to-head” with the companies it regulates. He expects child psychologist hires to integrate into the FTC’s operations in the same way.

The commission will start slowly by hiring just a handful of child psychologists, but Bedoya expects the number to steadily grow. The move comes as children’s online safety and the mental health impact of social media on youth are under mounting scrutiny, with significant legislation to regulate kids’ use of social media under discussion in the U.S. Senate.

Recorded Future News spoke to Bedoya by phone last week. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Recorded Future News: When did you begin contemplating having the FTC hire child psychologists to bolster the agency’s understanding of how social media impacts children?

Alvaro Bedoya: I'm almost embarrassed about not having focused on this as a privacy advocate or law professor, but once I became a parent and once I also started spending more time with other parents — and other parents of teens in particular — I started to see how so many young people had what very obviously seemed to be complicated at best relationships with their devices. I saw and I heard stories from parents about the mental health issues that their children were experiencing and how both the parents and, in many cases, the teens themselves, traced it to social media, traced it to compulsive use, traced it to feelings of inadequacy that were born on social media, a lack of sleep.

Once I started looking into this, I saw that it certainly would appear that some of the techniques that platforms use to keep young people online, that there's a very strong case that some of those may be harming young people. As a parent, I woke up to the fact that the fire alarm was going off, the lights were blinking red.

And then I got to the FTC. Every government institution has its own institutional culture, its own institutional approach to its mission and one of the things you learn about the FTC when you get here is that this is an expert agency through and through. People pride themselves on not running investigations or writing reports based on surface information. They pride themselves on building real in-house expertise on a problem and then applying that. Much of what the FTC does is measure things and technically evaluate things.

RFN: The FTC has expanded its ranks to add other types of experts — technologists and economists — in the past. How do you see this effort in comparison to those?

AB: At first the FTC was lawyers, it was a bunch of civil law enforcement attorneys who were investigating antitrust and consumer protection violations. Then they realized we need to have economists to help us figure out what some of these practices are doing for the economy. We need to actually put some dollar signs on this, we need to actually quantify the likely effect of some of the conduct that we're seeing in industry and in the American economy. We need to really measure it.

So they brought economists on and that's been completely invaluable. And now we've got 80 Ph.D. economists on staff who can help us make heads or tails of both competition issues and consumer protection issues.

Then, in the early 2000s, my old mentor David Vladeck was the head of the Bureau of Consumer Protection. David pretty quickly saw that we were going head-to-head with major technology companies who have a cadre of lawyers and technologists opposite us. And these are Ph.D. technologists, who are structuring the commercial surveillance systems, the advertising systems, the tracking systems, and we have none of those folks on staff.

Under David, the FTC started bringing on board full-time technologists. And first it was one, then it was two and now under Chai Khan, she has seen fit to have a dozen technologists full time on staff. My suspicion is that soon we'll have many, many more because she appreciates immediately how we cannot investigate the tech sector — we cannot effectively do enforcement in the tech sector — with an entire tranche of experience that the tech companies have missing from our bench.

RFN: Why do you think it's now time to bring child psychologists on as experts?

AB: I came to this from the mental health side of things and if I have a technical question I've got a dozen technologists I can ask about this. If I have an economic question I've got 80 Ph.D. economists I can ask. If someone is making an allegation about mental health harms, I have no full-time staff who are experts in the psychology of it.

In any investigation, there's various questions that need to be answered. There is the question of causation between conduct and harm. There's the question of harm.

You don't need to be a rocket scientist to understand that if someone's been defrauded of $90,000, this person's out $90,000. If someone's been injured by a product they've used you are able to ask for the medical bills and say there's some real harm here. But if you're presented with research alleging an increase in depressive symptoms, do I have the ability to say, ‘Well, is that clinical depression or is that something en route to clinical depression?’ Do I have the ability to differentiate between a mental health harm or an incipient mental health harm, and a child who is sad? There's a difference between those things, but I am not expert enough to know that difference.

I don't want to give the false impression that we don't have the ability to answer these questions right now [by relying on consultants used on an as needed basis]. I just think that we can send a strong signal to other law enforcement agencies in the U.S. by saying we need to have these folks in-house such that it's a standing capacity. This is valuable for the question of harm’s causation. And it's valuable for the question of damages.

RFN: You just returned from London where you met with officials from the Information Commissioner’s Office as well as other agencies regulating technology companies in the United Kingdom. Your goal was to learn more about their tough approach on this issue. What was your key takeaway?

AB: The key takeaway we learned from our visit to the UK is that psychologists aren't one trick ponies. They don't just look at allegations of mental health harms from social media use — and it's important to say allegations because I'm not making a specific claim here about a specific company.

Take the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) where behavioral teams, of which psychologists are a key part, are looking at any number of issues with that expertise in-house. The key thing we've seen from the British and the Danes and the Dutch is that they're also looking at dark patterns and what constitutes deception. What I'm really excited about is that if we bring some of this capacity in-house, we won't just be more capable of assessing some of these allegations around social media mental health, but also will be even more ready to evaluate some of these allegations around dark patterns and other deceptive practices online.

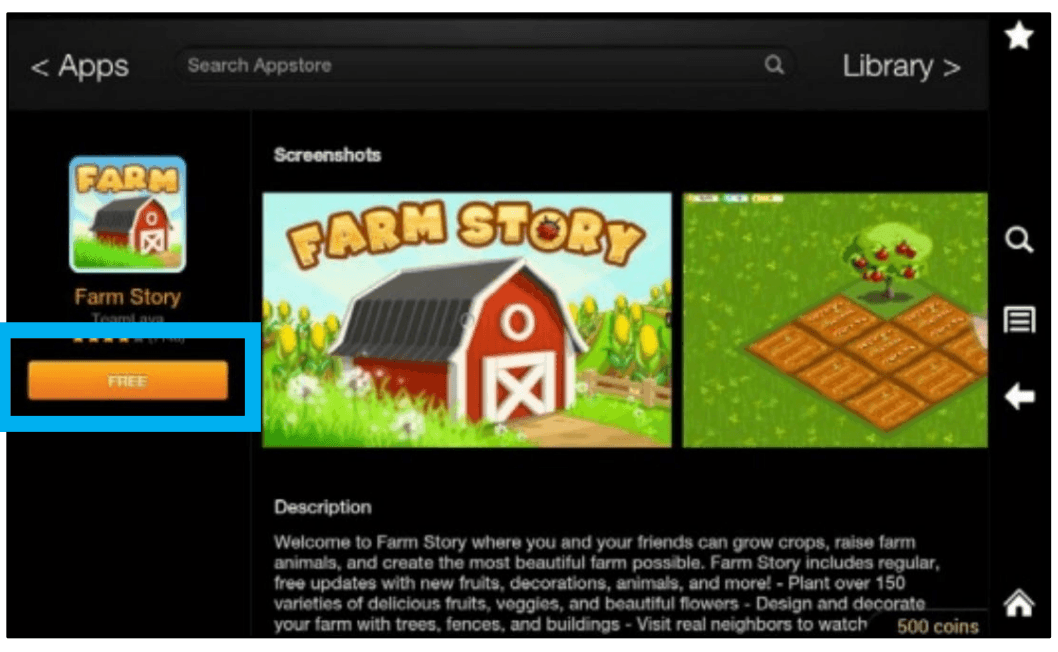

An example of a dark pattern highighted in an FTC enforcement action. Although kids gaming apps were advertised as "free," they allowed users to make in-app purchases.

An example of a dark pattern highighted in an FTC enforcement action. Although kids gaming apps were advertised as "free," they allowed users to make in-app purchases.

RFN: What is the implication for potential enforcement actions?

AB: That's what it would be informing. So I can't presuppose anything, but absolutely I would think that once we have the standing capacity, these folks would work on investigations. They would also work on strategy setting and reports. They could, in theory, also work on rulemaking.

The FTC also does these — I consider them best-in-class — investigative reports. Not law enforcement reports, but investigative reports, like we did on data brokers a few years back in 2014 where we are looking at industry and saying these are the top concerns.

RFN: What else did you learn in London?

AB: It was a three-day visit. We met with the frontline staff and the heads of the ICO and CMA. In each of those settings we spoke with them either about in-house psychologists or how they're confronting teen mental health issues online. So with ICO, they enforce the age appropriate design code. And so one thing we were very keen on trying to understand is how they're going about enforcing it and the different changes that have been made in response to some of their work. So one of the public changes, for example, is that, I believe it's TikTok, has turned off notifications for preteens during certain hours of the night.

Notice how elegant the change that is. This isn't censorship. This isn't blocking use of the app to users who are old enough by law to use it. This is simply eliminating a pull factor for teenage users who as a biological fact need more sleep than full grown adults. If they want to open up the app and use it at night, they can still do so. But this eliminates one of those dings on the phone that immediately pulls in the 13-year old, 14-year-old, 15-year-old who's trying to get a night of sleep.

RFN: So TikTok did that in response to their enforcement?

AB: That’s my understanding.

RFN: And you also met with the UK’s communications regulator?

AB: For the Office of Communications there's a new Digital Safety Act that we were trying to understand and how there's a category of content in it that is not illegal, but that is considered inappropriate. For example, eating disorder-related content that's not about helping people with eating disorders, but that may actually promote eating disorders. We learned a little bit about the different guidance documents they need to issue by law in order to confront this. There's different laws that apply in the UK than do here when it comes to content regulation and so that was more of a learning process too, just to understand what is happening across the pond on that.

We also met with the CMA. It has truly best-in-class behavioral teams that incorporate psychologists, that incorporate technologists, that incorporate attorneys, that I believe incorporate economists to conduct market studies. We met with their behavioral team to get a sense of the structure of the team, how they do their work, and just learned about the excitement there was internally about this.

RFN: Do you hope to grow the number you hire from several part timers to many more over time?

AB: That's my goal. But you always want proof of concept. So that's what we're doing right now — meeting experts, exploring different configurations, particularly after this UK trip. My goal is to have people in their chair, so to speak, by fall 2024, if not significantly sooner.

We don't need clinical psychologists or let me say that's probably not who we should bring on first. Clinical psychologists are treating children. What we want in this first tranche of experts is what some people call psychological scientists and what other people call social psychologists. These are people who are conducting research and evaluating research to get the sense of population level effects from certain conduct. We want people who are running econometric studies, peer-reviewed research to get a sense of the broad trends.

RFN: Even though you will start with a much smaller team than you have for technologists and economists, do you think of this as an equally important expansion of the agency’s mission?

AB: Absolutely it is part of that line of thinking. When Congress created us, they said, ‘we want an expert agency,’ and one of the underappreciated aspects of FTC is just how seriously we take it. And so yes, it's absolutely part of that tradition of systematically expanding our expertise.

RFN: Are you interested in video games’ impact as well?

AB: Do I think that video games cause mental health harms? I do not think that because I don't think the research bears that out. I think we now have a pretty rich tranche of research suggesting that most use of video games particularly now, where they're cooperative, you actually have people going online with their friends working cooperatively to do things — turns out that's actually pretty positive for child development.

At the same time, one of the cases I am most proud of FTC staff having brought is the Epic/Fortnite case where the privacy settings were such that complete strangers, adults could communicate with young children and that resulted in horrific cases of abuse and harassment, that very much drove mental health harms. Are kids playing video games cooperatively as good as running around in the woods? Maybe not. But is it a bad thing? I haven't seen evidence that it is, but platforms can have bad privacy settings that hurt children and that's something the FTC has been a leader in calling out.

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering digital privacy, surveillance technologies and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.