Ilya Sachkov versus the Kremlin

It’s July 26, 2023. And a judge is speaking inside a Moscow City courtroom.

The room is small and simple: Wood-paneled walls. Sage-green curtains. Fluorescent lights hum from a drop ceiling.

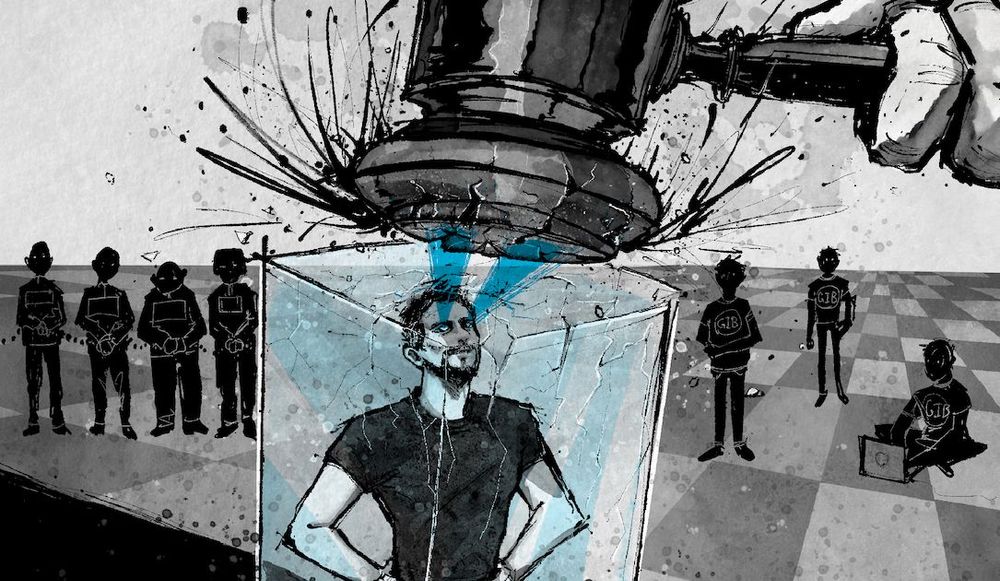

Wedged against the wall is a glass holding pen. Inside, a young man: 37 years old, wearing a black T-shirt.

His name is Ilya Sachkov, the founder and CEO of a homegrown Russian cybersecurity company called Group-IB. The firm is famous for tracking down some of the slipperiest criminals in the world. And Ilya is their public face.

Image: Group-IB

Image: Group-IB

For the past few years, Ilya's star has been on the rise. He’s given TEDx Talks, landed spots on 30-under-30 lists and won international awards.

Even the Kremlin appeared to be supportive.

President Vladimir Putin awarded Sachkov, right, a special prize in 2019 for young entrepreneurs who were helping Mother Russia. Image: the Russian government

President Vladimir Putin awarded Sachkov, right, a special prize in 2019 for young entrepreneurs who were helping Mother Russia. Image: the Russian government

But today in this quiet Moscow courtroom, it’s clear: The honeymoon is over.

As Ilya listens to the judge’s verdict, he stands up straight, clenches his fists and rests his knuckles on his hips.

Footage of Sachkov in court in July.

Footage of Sachkov in court in July.

It’s a heroic pose. Almost Superman-like. Which is funny, because, to many people, Ilya Sachkov is a superhero. He’s one of the biggest advocates for law and order in Russia.

So the question everybody has is: Why is Ilya Sachkov in this courtroom anyway?

* * *

Ilya Sachkov always loved a good mystery. Growing up, he used to lose himself in detective stories, in tales of eagle-eyed sleuths hunting down bad guys.

In 2003, when he was a teenager, he was at a local hospital awaiting surgery. To pass the time, he brought a book by Kevin Mandia, the cybersecurity expert, called “Incident Response and Computer Forensics.”

The book struck a chord. And as the morphine slipped into his veins, Ilya had an epiphany: Perhaps he could live out his childhood fantasy of being a detective — by becoming a cyber detective.

At the time, Ilya was just a student at Bauman Moscow State Technical University studying Information Security. But he quickly realized that he could use his burgeoning computer skills to help bring criminals hiding in the dark web into the light.

So he told his friend, Igor Katkov, about the idea.

“He was trying … to find how to improve our life,” Igor tells the Click Here podcast.

Igor remembers Ilya as an ambitious kid laser-focused on making a difference in the world. He called Ilya’s enthusiasm “overwhelming.”

Ilya was persistently optimistic, always one to wear a smile. And his brain seemed to be working on new ideas 24/7. At one point, the duo had considered starting an online department store.

“We were trying to invent some new business,” Igor says. “Our thoughts were to create an electronic market … to sell clothes in Russia.”

But Ilya felt that life should be more exciting — and more meaningful — than merely selling cargo shorts over the internet.

That’s when he had the fateful idea to combat cybercrimes instead.

One of Ilya’s other big inspirations was a 1979 TV detective series called “Mesto vstrechi izmenit nelzya” — in English, “The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed.”

In Russia, the fictional five-part show is a cult classic. A young detective joins the Moscow Criminal Investigations Department and makes a fateful attempt to track down a murderous gang of bandits.

In one episode, there’s a famous line: “A thief’s place is in prison.”

Nearly 50 years later, that line is a meme in Russia. It gets quoted all the time. Even President Vladimir Putin is known to use it, without irony, when discussing imprisoned opposition figures.

But for Ilya, the line captured an essential truth. “He thought that, if we have some criminals in Russia, they should go to prison,” Igor says.

It was settled. Group-IB was born.

* * *

Over the next 15 years, Ilya and Igor began tracing the digital footprints of some of the world’s toughest cybercriminals.

In 2013, Group-IB found malware targeting Russian stock-trading. The next year, it tracked down digital bank-robbers who had stolen a billion rubles. In 2016, it sniffed out a gang that had tricked ATMs into spitting out money on demand. And in 2017, the company confirmed that North Korea was the source of an $81 million heist from the Central Bank of Bangladesh.

But what really made Group-IB special was how it carved a niche for itself. It was one of the only companies in the world that had Russians hunting other Russians.

By the late 2010s, the company was growing into a juggernaut with clients all over the world. Revenues were climbing. Satellite offices were expanding in new cities. Igor had moved on to new opportunities, leaving Ilya to become the face of the company.

Ilya started giving lectures and getting media attention. By 2019, he was standing in a palatial ballroom accepting handshakes from Putin.

“I think Ilya is a very famous person,” Igor says. “A lot of people in Russia were fans of his.”

Ilya gradually became a spokesperson for law and order in Russia. And he was inspiring kids to go into tech.

“He was an example of healthy patriotism,” says Dima, a 30-year-old IT worker who looks up to Ilya. “He’s an example of a Russian engineer who thinks and thinks about the country, about how to do better.”

But with his profile on the rise, Ilya was also on the brink of ruffling the wrong feathers. In today’s Russia, the relationship between cybercriminals and the Kremlin is complicated.

“Russian cybercriminals can operate from within Russia … very freely, almost by fiat, with the will of the Russian state,” says Alexander Leslie, a threat intelligence analyst at Recorded Future.

That gentleman’s agreement is actually coded directly into cybercrime operations.

“There are a lot of fail-safes that cybercriminals had built into malware itself to ensure that attacks don’t happen against Russian entities,” Leslie says. “And if they do, it immediately self-destructs.”

As a result, most Russian cybercriminals choose to attack targets in places like the U.S. and Europe.

The Kremlin, in return, turns a blind eye.

“When these attacks happen, there are small-scale disruptions to everyday life around the world,” Leslie says. “This does serve a purpose for Russia as that harbinger of chaos in cyberspace.”

In other words, it’s another way for Russia to project soft power. “If you target entities in the U.S., you can effectively do whatever you want,” Leslie says.

Take, for example, Maksim Yakubets. He’s wanted by the FBI and the U.K. National Crime Agency. The FBI is currently offering a $5 million reward for information that could lead to his arrest.

Yakubets is believed to be the leader of the Russian hacking group Evil Corp. The gang has allegedly stolen more than $100 million from bank accounts around the globe.

And yet, Yakbuets leads a brazenly public life in Russia.

You can watch videos of Yakubets driving his Lamborghini, tires squealing as he does doughnuts on a public square. (According to the BBC, his custom license plate spells out “THIEF.”) He’s posted videos on social media of himself playing with a lion cub. Even his wedding was attended by Russians with connections to the Kremlin.

In today’s Russia, the old line “a thief’s place isn’t in prison” doesn’t ring true anymore.

If you’re a cybercriminal, a thief’s place is outside — and in the open.

* * *

By the late 2010s, Ilya Sachkov felt frustrated with Russia’s permissive treatment of cybercriminals. He believed that Russia could compete with the U.S. and Japan in the cybersecurity sphere — if only it would try.

So Ilya harnessed his growing fame and began speaking out.

He started first with a 2016 TEDx Talk titled “Cybercriminals are criminals. And it’s time to take action.”

Then, in 2020, he took the stage at a televised tech conference and issued a very public broadside about Russia’s decision to turn a blind eye to cybercrime. His audience included the prime minister of Russia, Mikhail Mishustin.

“When the whole world says that Mr. Maxim Yakubets, a hacker who drives around in Moscow in a Lamborghini with BOP numbers, is a computer criminal, the creator of the Dridex virus, every engineer in the world knows about it … this affects the image of Russian companies that export information security,” Ilya said.

Sachkov at a 2020 tech conference in Innopolis, Russia. Image: the Russian Government

Sachkov at a 2020 tech conference in Innopolis, Russia. Image: the Russian Government

Turns out, chastising the Kremlin for not going after a wanted criminal like Yukabets was a bold move.

According to the U.S. Treasury Department, Yukabets is not just the alleged leader of Evil Corp. He’s also been “working for the Russian FSB,” or Federal Security Service, since 2017.

Ilya wanted the government to arrest Yakubets. But, if the allegations are true, the reason the Kremlin never arrested Yakubets is because he was working for it.

The next year, in 2021, Ilya made this exact point. He released a video on his Telegram channel in which he suggested that Russian cybercriminals were working with, or for, the Kremlin.

“Everyone has a purpose,” he says. “Apparently, mine is precisely to reveal the monstrous mistakes that allow criminals, including those in an all-powerful department, to behave with impunity.”

* * *

In September 2021, a few months after Ilya recorded that Telegram video, Group-IB’s office in Moscow was flipped upside-down. The FSB raided the office and hauled away boxes of documents and valuable servers.

Igor Katkov, who now lives in Cyprus, was distraught when he heard the news: “It was really scary. All of my friends were texting me, ‘Do you know what is happening? Did you see this?’”

Soon, Ilya was in handcuffs.

At first, Igor figured this was all just a big misunderstanding: “Everything will be OK because sometimes it happens. They will just ask some questions and let him go.”

Instead, Ilya was kept in pretrial detention for two years. The charges against him would never be made public. The trial was held in secrecy.

There are whispers that Ilya was accused of sharing state secrets, perhaps working with the United States. But those reports remain unconfirmed.

* * *

When Ilya made his accusations against the Kremlin in 2021, he appeared to understand that his days as a free man were numbered. But he still didn’t lose his boyish optimism.

“Wherever I am, I’ll tell you these words: Everything will be perfect,” he said in a video recorded in 2021 and released just before his sentencing.

Ilya maintained that same cheerful demeanor on the day of his sentencing. While everybody else in the courtroom looked glum, Ilya posed like Superman behind the glass and wore his trademark smile.

Sachkov and his legal team. Image: Ilya Sachkov / Telegram

Sachkov and his legal team. Image: Ilya Sachkov / Telegram

He continued smiling as the judge declared him guilty of treason, sentencing him to 14 years at a strict-regime penal colony.

Outside the courthouse, the sky was gloomy with rain. But Ilya’s mother — with a bob of red hair, cat-eye glasses, holding a plaid umbrella — was also optimistic.

“I’m certainly proud of him,” she said. “He’s a superhero … And I am very glad that no one turned away from him, that all his friends, all his associates are with him.”

His mother is right. When Click Here spoke to Igor, we asked if he had a message for his old colleague.

“We all love you,” he said. “You are our friend. Please come back as soon as possible. We will do everything we can to make this happen.”

Additional reporting by Sean Powers.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”