IcedID malware gang positioning itself as one of the Emotet replacements

The IcedID malware gang has ramped up operations over the past few weeks in an attempt to position itself as one of the contenders to fill the void left in the cybercriminal underground following the takedown of the Emotet botnet in January this year.

First spotted in the wild back in 2017, the IcedID malware, also known as Bokbot, initially started out as a classic banking trojan.

In its first campaigns, the IcedID gang operated by sending email spam containing malicious Office documents that infected victims with their payload. The goal of these early IcedID operations was to stealing login credentials for online banking accounts, so the IceID gang could access e-banking accounts and steal customer funds.

But IcedID came on the scene after banks had been attacked and abused by tens of other banking trojan gangs since the mid-2000s. By the time IcedID launched into operation, banks had already started to deploy multi-factor authentication solutions to protect their customers.

Seeking a new way to profit, the IcedID gang followed in the footsteps of other fellow banking trojan operations such as Dridex, Emotet, and Trickbot, which, circa 2017 and 2018, began updating their code to transform their malware into a "downloader."

Also known as a Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) model, today, many former banking trojans operate by renting access to infected computers to other criminal gangs — where they download/load other malware, hence the name of "downloader" or "loader."

Across the years, Emotet gained a following in underground circles as the top MaaS provider, primarily due to a large set of features, fast development cycle, and a high infection rate for their malspam campaigns.

But this success also drew the ire and attention of law enforcement, which after months of tracking the Emotet botnet, successfully took over its server infrastructure at the end of January 2021 and shut down its operations.

This sudden takedown forced many of the cybercriminal groups who were relying on the Emotet botnet to provide them access to infected computers and corporate networks to seek alternatives.

Dridex, Trickbot, and Qakbot were some of the beneficiaries of the Emotet takedown, seeing a spike in activity since January 2021.

IcedID slowly gaining a following

However, over the past month, security firms and malware analysts have started noticing a spike in activity from IcedID, which is now slowly starting to rival the three above-mentioned botnets and is also staking a claim for some of Emotet's past market share.

"Over the last two months, we've noticed an increase in IcedID campaigns," Randy Pargman, senior director at security firm Binary Defense, told The Record in an interview earlier this week.

Fellow security firm Check Point also made a similar observation in a report published yesterday, ranking IcedID as the second most active malware strain for the month of March 2021, right behind Dridex.

William Thomas, a malware analyst at UK security firm Cyjax also confirmed this trend in an interview with The Record earlier today.

But the biggest and most serious warning comes from Microsoft itself, which, via its Microsoft Defender antivirus and Microsoft 365 cloud platform, has had the best view into recent IcedID operations among all security vendors.

In a series of tweets on Tuesday, the OS maker confirmed what everyone in the infosec industry had been quietly thinking — that IcedID is now a serious contender to fill the void left by Emotet.

The recent surge of IcedID campaigns indicate that this malware family is likely being used to fill in some of the void left by recent malware infrastructure disruptions. We are tracking multiple active IcedID campaigns of various sizes, delivery methods, and targets. pic.twitter.com/Qfsii7q0uu

— Microsoft Security Intelligence (@MsftSecIntel) April 13, 2021

IcedID campaigns growing in sophistication

But Microsoft didn't just point the finger at an increase in malspam (email spam carrying malicious documents) but also highlighted the diverse delivery methods that the IcedID gang has been recently using to spread its payload. This diversification in IcedID delivery methods suggests the malware's operators are now reaching a level of sophistication seen with other MaaS operations such as Dridex, TrickBot, and Qakbot.

In a Signal chat, Pargman told The Record the exact same thing, noting that besides IcedID campaigns becoming more frequent, they "also increased the variety of creative ways that the threat actors are using to get an initial foothold on employees' workstations."

Among these recent delivery tactics, security researchers have seen:

- the abuse of public contact forms to trick corporate employees into installing the malware;

- IcedID campaigns that relied on delivering Excel (XLS) spreadsheets containing malicious Excel 4.0 XLM macro scripts [1, 2, 3];

- the use of password-protected ZIP files hiding malicious Word and Excel files as a way to evade scans from email security solutions;

- the use of fake software installers (such as the Zoom app) to trick victims into infecting themselves;

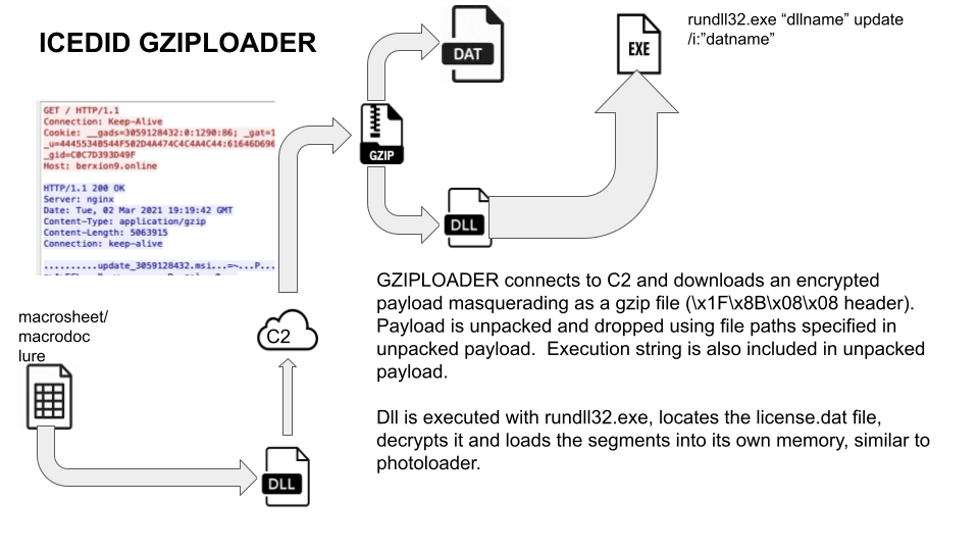

- the use of GZIP files (in a campaign dubbed GZIPLOADER) hiding malicious XLS spreadsheets and Word documents;

- the use of COVID-19 lures; and many more.

James Quinn, a malware analyst at Binary Defense, told The Record that based on the broad spectrum of these campaigns, this also suggests "that multiple groups are using IcedID as a dropper" (with dropper being another name for downloaders/loaders).

As for what it "drops," this varies per infected system.

"Once IcedID has been covertly installed on a computer, it is used for multiple purposes," Pargman told The Record.

"It steals passwords that have been saved in web browsers on an ongoing basis, refreshing them every few days."

"It also turns the infected computer into a back-connect proxy server, allowing the threat actors to tunnel network connections through the infected computer to the Internet," Pargman added. "This allows the bot operators to download files, test stolen passwords or authentication tokens against websites, and do any other recon activities they wish to while hiding behind the IP address of the victim."

"At any time of the attacker's choosing, IcedID can be used as a conduit to deliver Cobalt Strike beacon, as we have observed on more than one occasion, or possibly any other payload of the attacker's choosing. This gives the attacker interactive control of the infected computer and allows them to use it as a beachhead to attack the rest of the business network and expand their access," the Binary Defense exec said.

Catching the eye of ransomware gangs

But with its rise in popularity, IcedID is also becoming popular with the apex predators of the cybercrime ecosystem — namely, ransomware operators.

Before its operations were disrupted by French and Ukrainian authorities, customers of the Maze/Egregor Ransomware-as-a-Service had previously rented access to IcedID infected computers to gain access to corporate networks to steal data and encrypt files.

But as the Maze/Egregor attacks stopped, incident responders are now reporting that IcedID is currently being used to deploy another ransomware strain, known as REvil (Sodinokibi).

All of these recent IcedID reports listed above confirm that this once small-time operation has seen a chance to grow and is capitalizing on its opportunity.

With ransomware gangs slowly adopting IcedID as an intrusion vector, companies will now need to prioritize detections for this malware family in the same way they have been previously prioritizing the detection of similar threats like Emotet, TrickBot, BazarLoader, SDBot, and others. If they don't, they might end up starting down the sights of a multi-million-dollar ransom demand.

Catalin Cimpanu

is a cybersecurity reporter who previously worked at ZDNet and Bleeping Computer, where he became a well-known name in the industry for his constant scoops on new vulnerabilities, cyberattacks, and law enforcement actions against hackers.