Healthcare Providers Were Warned of a Ransomware Surge Last Fall. Some Still Aren’t Sure How Serious the Threat Was

Late last October, when the U.S. government warned of an imminent ransomware threat to the country’s hospitals and healthcare providers, many in the industry had a similar reaction: they paused, took a deep breath, and braced for impact.

But one of the organizations tasked with distributing critical threat information across the healthcare sector was not among them, instead turning a skeptical eye on the government’s alert.

The Threat Intelligence Committee of the Health Information Sharing and Analysis Center (H-ISAC), which represents more than twenty of the world’s largest healthcare providers, saw no evidence of significant new threat activity in late October. Convinced that H-ISAC’s 600-odd members by and large had adequate defenses in place, the committee worked to prevent alarm from spiraling into panic.

“The intelligence warnings we felt were based on information that did not indicate the existence of a sophisticated malware threat that would cause severe damage in the health sector,” explained Errol Weiss, H-ISAC’s Chief Security Officer.

In H-ISAC’s eyes, time would vindicate that assessment: a large-scale attack never came.

The Record spoke with cybersecurity experts in government, the healthcare sector, and the threat intelligence community who strongly defended the quality of the government’s intelligence and the necessity of the October alert. Each offered different explanations as to why H-ISAC never saw an uptick in attacks if its interpretation of the alert was wrong.

Some believe that the attacks did not wreak havoc because the alert helped defenders neuter them in their infancy. Others assert the attacks did occur—indeed, that they are ongoing—but they slipped through gaps in H-ISAC’s information-sharing network, which is reliant on voluntary reporting between generally well-resourced healthcare organizations, some of which reside outside the United States.

NEW INTEL: Ransomware attacks on US hospitals, during a pandemic, are probably the most dangerous cyberattacks in the US to date. This problem is out of control and people will get hurt. We're sharing intelligence to arm defenders. 1/x https://t.co/CDtzc3tEG7

— John Hultquist (@JohnHultquist) October 29, 2020

Wherever the truth lies, two things are clear: Many in the healthcare sector do not share a common understanding of what happened, or didn’t, last fall, and that dissonance—the product of corporate non-disclosure agreements, governmental classification, and gaps in the sector’s incident reporting mechanisms—extends beyond H-ISAC.

The conflicting views on the government’s alert also highlight one of the central challenges involved in defending the U.S. healthcare sector: when sharing threat information with a large and heterogeneous community of frontline IT staff, threat intelligence analysts must walk a tightrope between providing clear information and avoiding “FUD”—Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt.

That tightrope will rarely satisfy everyone, said Josh Corman, chief strategist for healthcare and Covid-19 at the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency.

“In difficult situations, the best policy is to be forthright,” said Corman. “Whether it’s too aggressive or too downplayed, both can cause harm.”

A threat of what kind?

By the fall of 2020, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were being buffeted by ransomware attacks on a regular basis. But to Weiss, the H-ISAC CSO, the October warning heralded something far worse.

The government’s alert had fingered the Russian cyber-crime nexus behind Trickbot, a one-time banking trojan now commonly used to drop ransomware. Just one month prior, Trickbot had seeded one of the largest medical ransomware attacks in U.S. history. Now, there were rumors the botnet’s operators were out to cause havoc.

According to the New York Times, the FBI had received a tip from Hold Security, a cybersecurity company based in Milwaukee, right before the government issued its alert. Hold had uncovered messages in dark web forums indicating that Russian cyber-criminals were planning a coordinated attack against more than 400 U.S. healthcare facilities.

A large-scale attack designed to maximize disruption in the healthcare sector was Weiss’s worst nightmare. But the government’s alert did not cite that risk directly, and Weiss felt that Hold’s warning had been blown out of proportion by the media.

Uncertain whether classified information had triggered the government’s alert, Weiss pressed others in the industry for more information. Yet everyone he spoke with kept pointing him back to the intelligence provided by Hold—a threat he felt H-ISAC was already equipped to handle.

That was a problem, said Weiss, because many healthcare organizations within H-ISAC were taking media reports of a major incoming attack at face-value.

“On one end, I was a bit concerned because some members were considering going as extreme as disconnecting email or disallowing attachments from flowing into the network, which can create operational issues for healthcare providers,” said Weiss.

At the end of each month, or in the event of an emergency, H-ISAC’s Threat Intelligence Committee issues advisories on the global threat level to its membership. The committee did not have to schedule an emergency meeting in October because the government’s alert fell at the end of the month. When it did meet days later, it decided not to raise the threat level for the group’s members, though it did cite the government’s warning.

There was little disagreement surrounding that decision, according to Weiss. “Ultimately, when we looked across the sector, what we saw was the normal state of affairs,” he said

“In difficult situations, the best policy is to be forthright”

Josh Corman had a long career in information security before he was brought on by CISA to help with their COVID-19 response. Now a Senior Advisor at the agency, Corman does not appear cowed by the life-or-death stakes of his new role so much as he brandishes them.

Offhand, he knows how long of a delay in emergency care can prove fatal for patients who have suffered a heart attack (four-and-a-half minutes) or a stroke (four-and-a-half hours). He knows what percentage of U.S. hospitals lack a single security employee (85%, though the figure is likely worse after the pandemic). And he knows how long it took individual healthcare facilities to recover from the slate of ransomware attacks in October.

Which may explain why Corman prefers to be direct.

“Our position is that this was not normal [ransomware] activity,” he said, at the same time denying that the intelligence from Hold Security had played a role in the government’s assessment: “Our work was independent, and any conflation is on the people doing the conflating.”

Hold Security did not respond to multiple requests for comment via email as well as the company’s “Contact” page.

Corman identified three factors that drove the government’s decision to issue the alert last October. First was a credible warning of an incoming threat from a plurality of threat actors, some of whom were unleashing ransomware attacks in under three hours. The compressed dwell time, Corman said, worried the government because it indicated an “intent to do damage.”

Furthermore, the FBI, CISA, and the Department of Health and Human Services were each dealing with an extremely high “caseload” of ransomware incidents against healthcare facilities. Part of what made the activity so troubling, according to Corman, was not the raw number of victims but the number of facilities swept up in each attack.

Many healthcare organizations run multiple hospitals, meaning an attack against one entity’s IT system can debilitate a wider number of facilities operating under their umbrella. In one attack in September, for example, the same threat actors flagged in the October alert had ensnared IT systems at roughly 250 U.S. hospitals run by Universal Health Services.

On top of all that, Corman said, the government continued to learn of new attacks from the victims themselves, which indicated that the victim count was higher than the government could see. The attack against Universal Health Services only came to light after employees began posting about it on Reddit.

Overall, Corman is adamant the government’s intelligence was top notch. But he brushes aside questions about the nature and scale of the threat relative to public perception. What matters more to him is that the government made the right decision. (Classification, of course, may also play a role in Corman’s evasiveness.)

“Even if we were to take the premise that we have the same ransomware threat that we always do, the impact of that is far more severe during a pandemic,” said Corman.

“A chess game with no checkmate”

In many respects, the dissonance between the government and H-ISAC boils down to a simple but important distinction: whether the “imminent” ransomware activity the government identified represented an updated version of an existing problem or if it posed a grave new threat to the sector as a whole—an image the government did not directly cite or endorse, but one it nonetheless conjured in the popular imagination.

When it comes to last fall, the question is harder to answer than most assume. That is because the coordinated attack many feared at first seemed to flood across the country.

In the hours and days after the government’s alert, media reports surfaced of multiple hospitals whose electronic health records systems—the lifeblood of modern patient care—had been knocked offline by cyberattacks, including at the University of Vermont Health Network, Sky Lakes Medical Center in Oregon, and the St. Lawrence Health System, based in New York.

But as the dust settled, it became less clear whether those incidents represented a coordinated uptick in threat activity or if increased media attention had simply produced a form of confirmation bias, bringing to light more incidents even as the turbulent situation below the surface kept pace.

"In difficult situations, the best policy is to be forthright,” said Corman. “Whether it’s too aggressive or too downplayed, both can cause harm.”

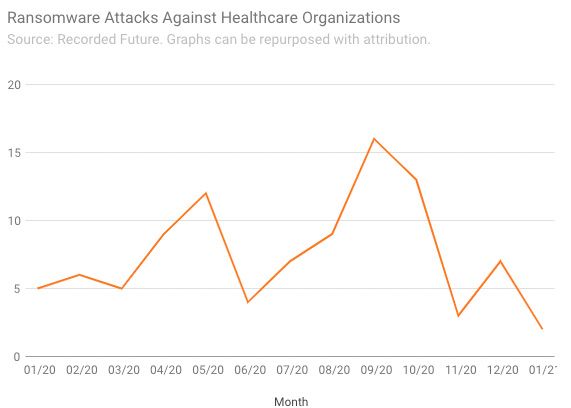

Available data on reported ransomware attacks against the healthcare sector does not reveal a “statistically significant” uptick last October, said Brett Callow, a ransomware researcher at cybersecurity firm Emsisoft. Allan Liska, a ransomware researcher at Recorded Future, agreed that the late-October attacks represented a “blip” in “very bad year of ransomware attacks against healthcare providers.” (For his part, Liska believes the government’s alert played a big part in that.)

That data is consistent with the experience of Greg Garcia, Executive Director for Cybersecurity at the Healthcare and Public Health Sector Coordinating Council (HSCC).

Like H-ISAC, HSCC serves as a sort of connective tissue for healthcare providers as they defend against digital threats. But whereas the H-ISAC works at tactical level—helping members share and respond to concrete digital threats on a daily basis—the HSCC focuses on longer-term issues.

Garcia was therefore not involved in the H-ISAC threat briefings or discussions in late October. Nonetheless, he confirmed Weiss’s assessment of the sector’s response to the intelligence it received from the government, as well as the pace of attacks it was seeing in October.

“It’s true we had a number of attacks, but we had difficulty connecting the dots,” said Garcia, a former DHS official and someone who is well-versed in the challenges the government faces in protecting critical infrastructure.

Overall, Garcia described the period surrounding the government’s alert as nothing outside the ordinary for HSCC, whose 300-odd members have battled an alarming increase in ransomware attacks for well over a year.

According to data from Emsisoft, 560 U.S. healthcare providers were hit with ransomware in 2020. Amid a year like that, October, bad as it was, did not stand out for Garcia.

Garcia is focused on the long game. Cybercrime against the healthcare sector, he said, is a “chess game with no checkmate.”

What might have happened

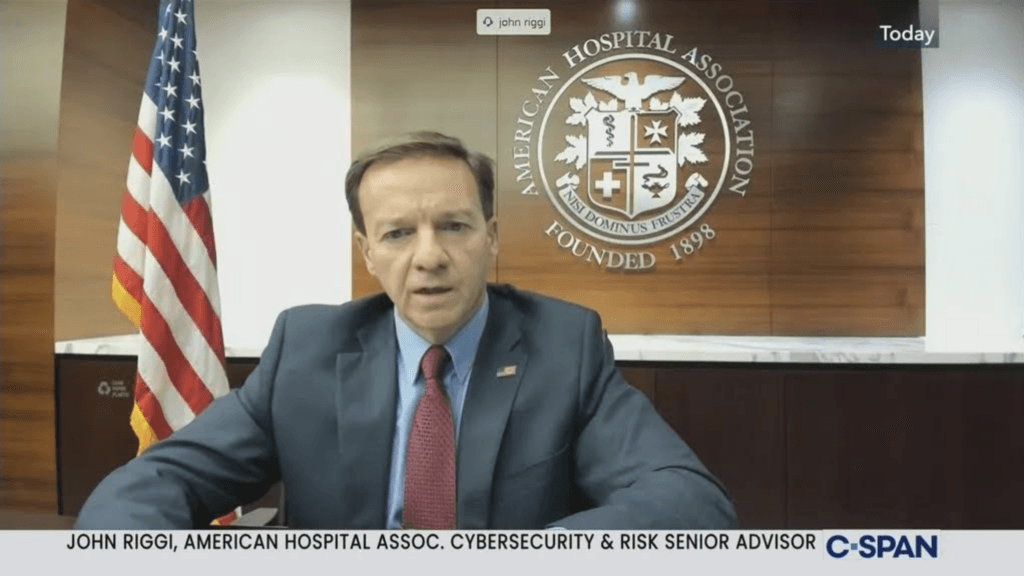

As the Senior Advisor for Cybersecurity and Risk at the American Hospital Association, an industry group comprising more than 5,000 U.S. hospitals, John Riggi keeps close watch over much of the critical infrastructure that sat in the crosshairs last fall.

A former FBI official, Riggi has experience with the class of people who would extort hospitals amid a pandemic, and the government’s sometimes thankless role in stopping them. He is quick to point out the critical difference between what happened and what might have happened.

“A lot of hospitals took somewhat extraordinary defensive measures in October,” explained Riggi, who believes the government’s alert, and all the behind-the-scenes measures it took to share timely intelligence with the healthcare sector, foiled many attacks early on. “The rapidly declassified information helped the entire sector defend.”

Riggi said that when hospitals received the threat indicators provided by the government, several learned that the attackers were scanning their networks—or, in Riggi’s words, “knocking at the door.” Coupled with the government’s advice on how to remediate vulnerabilities in the hospital’s IT systems, that knowledge mitigated many of the attacks, Riggi believes.

Another telling, if limited, window into how dangerous things were last October comes from the personal accounts of cybersecurity experts and incident responders, who spotted the re-emergence of the Russian cyber-crime network last September and watched as it developed alarming new attack patterns by October.

Many of them worked long hours last fall to fend off attacks against the healthcare sector.

Ohad Zaidenberg, the Founder and Executive Director of the CTI League, a non-profit group that provides cybersecurity assistance to global healthcare providers, said his group formed a 28-member emergency task force to assist the U.S. government in late October. He called the events leading up to the government’s alert a “crisis” that was “overwhelming” for the task force.

John Hultquist, Vice President for Intelligence Analysis at FireEye, said that the firm’s incident response teams were working around the clock in October. Nonetheless, many healthcare facilities FireEye monitored were not taking proper preventative measures. One of the goals of the government’s warning, Hultquist suggested, “was to get people to take it [the threat] seriously.”

According to Hultquist, that worked: The wave of attacks buffeting FireEye’s incident response teams dropped off sharply after the government’s alert.

The haves and the have-nots

Listening to Riggi and Hultquist, it is tempting to interpret the events of last fall as an intelligence success, clean and simple: The attacks left little trace because they were thwarted.

But Corman, the CISA official, is not so sure.

In the absence of more effective incident reporting mechanisms within the healthcare sector, explained Corman, an authoritative assessment of the damage incurred last fall remains out of reach. That means there is potentially a significant gap between what the public—and, to a lesser extent, the government—can see versus what actually happened.

For example, The Washington Times acquired data from the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (ICC) last month indicating that the FBI had received 302 ransomware reports in October of 2020, a record monthly tally. But the ICC does not organize data by industry, so it is difficult to tell just how battered the healthcare sector was, and it relies on self-reported data, suggesting that the extent of the problem could be worse.

Corporate non-disclosure agreements, governmental secrecy, and porous, personal data-focused breach notification requirements all play a part in obscuring the truth. But the root of the problem runs deeper, according to Corman.

Many U.S. healthcare facilities do not have the resources to hire their own security staff, let-alone bankroll an elite cybersecurity vendor. Furthermore, many of those companies are unwilling to share information with the government because they are unaware of sector-specific or government-run information-sharing programs, like the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act of 2015. They therefore view transparency as an invitation for regulatory backlash.

This gap between the “haves” and the “have nots” in cybersecurity is what has Corman so worried over the long run. He said CISA is working hard to overcome it.

Characteristically, he is unapologetic about those efforts.

“CISA’s mission is to speak on behalf of the have nots. The goal is to protect all of healthcare, not just those fortunate enough to have a robust security team.”