Hacks tied to Russia and Ukraine war have had minor impact, researchers say

Although politicians and cybersecurity experts have warned about the potential for widespread hacks in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a new study finds that attacks linked to the conflict have had minor impact and are unlikely to escalate further.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, the University of Edinburgh and the University of Strathclyde examined data from two months before and four months after the invasion. They analyzed 281,000 web defacement attacks, 1.7 million distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and hundreds of announcements on Telegram used by hackers to coordinate their activity.

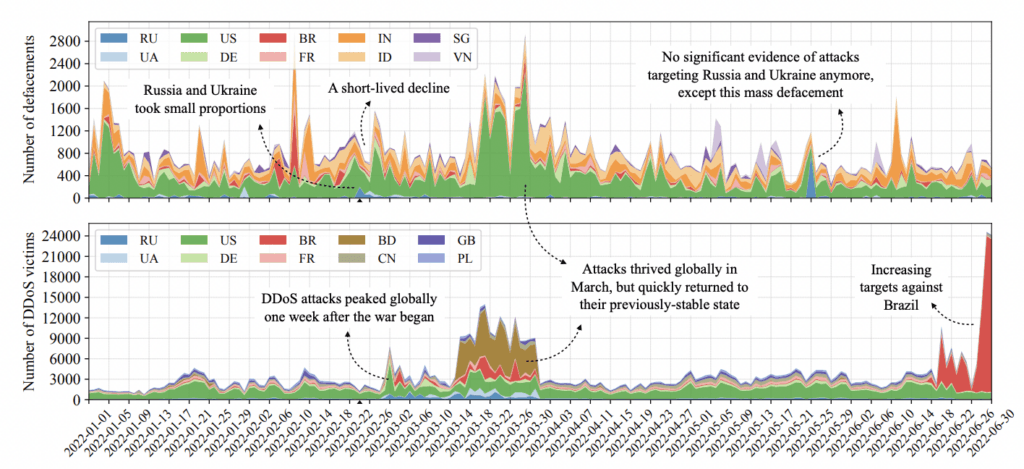

According to the analysis, which was published last week, Russia was the first to be attacked at scale, followed by Ukraine a few days later. The increase in cyberattacks lasted for about two weeks before returning to the pre-war levels.

At the time, ransomware gangs around the world pledged allegiance to one side of the conflict or the other. Some researchers argued that hacktivists would wreak havoc on the stability of cyberspace, signaling a future where war would involve hybrid conflicts that would be chaotic and unpredictable.

But according to the research, hacktivists mostly used DDoS attacks that temporarily made websites unreachable, as well as defacement attacks that altered websites’ appearance. Rather than targeting critical infrastructure, as expected, hackers attacked “harmless, defunct, or trivial websites” with Russian or Ukrainian domain names, including food delivery services, news websites and streaming services.

Most of the attacks were carried out by low-level cybercriminals using widely available tools. “Websites providing DDoS as-a-service abound, so launching attacks is straightforward, even for those without much technical skill,” the six researchers behind the study wrote.

Most of the researchers involved in the study are professors who have extensive cybersecurity experience and have published scholarly papers on the topic. The study was published on arXiv.org and is awaiting peer review.

Due to the widespread availability of these services, DDoS activity continued for weeks, while defacement attacks were carried out in the first couple of days.

“[Defacement] was widely used as the conflict started because it could deliver political messages and propaganda,” the researchers wrote. Later, attackers simply lost interest and ran out of targets.

Many hackers didn’t have a strong political viewpoint on the war — they attacked “just for fun or as a hobby,” the researchers said. “They appear to be classic cybercrime entrepreneurs, whose own use of their tools outside a business context occasionally takes a political dimension."

Although a lot of attention has recently been given to Ukrainian and Russian cyberattacks, they still make up a small portion of global cyberattacks, the researchers noted.

With DDoS attacks, for example, the U.S. victims still dominate, with almost 25% of all attacks, followed by Brazil (12%) and Bangladesh (8%), according to the researchers. Ukraine and Russia together only make up about 5% of DDoS attacks.

Some cybercrime activities were effective during the war, according to the research: leaks of high-profile datasets gathered from Russian public services, for example, as well as ransomware attacks using wipers.

“But the so-called ‘defacements’ are the rough equivalent of breaking into a disused shopping center on the outskirts of a mid-sized Russian city and spraypainting “Putin Sux” on the walls,” according to researchers.

“These are trivial acts of solidarity, teenage competition, and expressive delinquency, not a contribution to the armed conflict in any real sense,” they said.

Daryna Antoniuk

is a reporter for Recorded Future News based in Ukraine. She writes about cybersecurity startups, cyberattacks in Eastern Europe and the state of the cyberwar between Ukraine and Russia. She previously was a tech reporter for Forbes Ukraine. Her work has also been published at Sifted, The Kyiv Independent and The Kyiv Post.