Forced offline, many in Myanmar turn to the dark web

When Myanmar’s military deposed the country’s democratically elected ruling party leaders last month, they were quick to also target the nation’s internet infrastructure.

Three days after the military initiated the coup, a letter from Myanmar’s Ministry of Communications and Information said Facebook would be shut down due to “people who are troubling the country’s stability” using the platform to spread “fake news and misinformation.” The following day, the military extended the ban to other platforms, including Twitter and Instagram. And one day after that, the military initiated a nationwide internet outage.

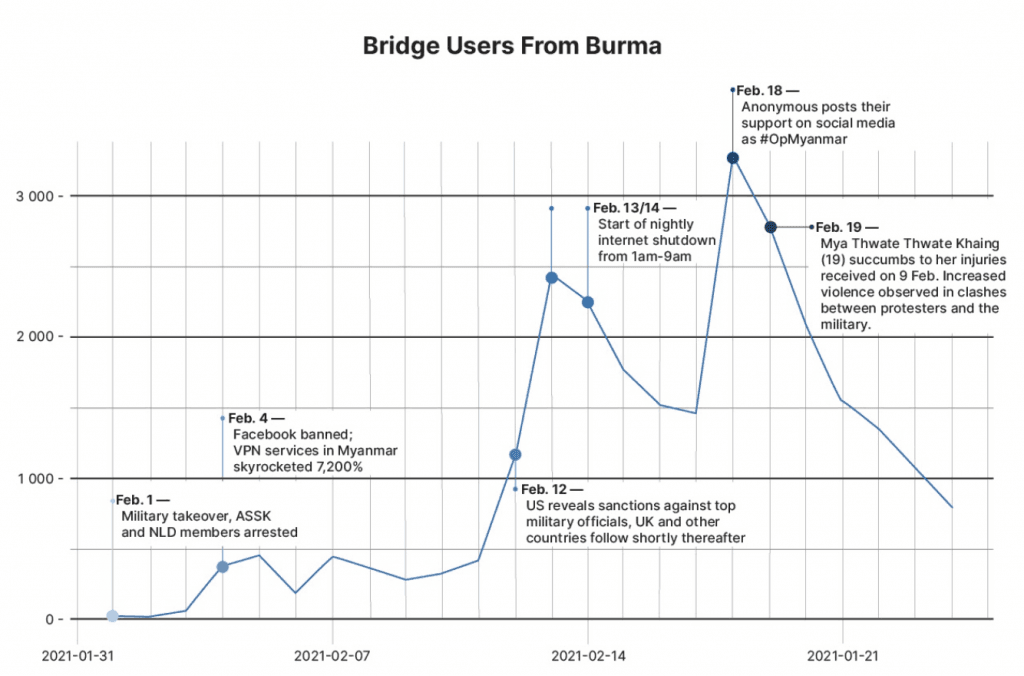

In what’s become a typical response to authoritarian crackdowns, Myanmar citizens have turned to the dark web to bypass new censorship measures, hide internet traffic from the military regime, and communicate with family both inside and out of the country. According to a report published today by Recorded Future that used estimates from The Tor Project, thousands of people in the country turned to the open-source browser to anonymously communicate with others and access news reports.

Confirmed: Internet has been cut in #Myanmar from 1 am Wednesday local time, the 38th recurring night of military-imposed shutdowns

Meanwhile:

Mobile data disabled: 9 days

Public wifi limited: 7 days

Online platforms filtered since February

https://t.co/Jgc20OjIDx pic.twitter.com/e7JT3pMR93— NetBlocks (@netblocks) March 23, 2021

“Before the coup, Tor usage in Myanmar was very, very low—practically zero,” said Charity Wright, a cyber threat intelligence analyst and co-author of the report. “After the coup it rose very rapidly. It was apparent that this was a desperate effort on the people’s part to access information and contact family and friends.”

Since a spike in late-February, Tor usage dipped in the country, which could be attributed to reports on various forums that the Myanmar military was searching for people who had Tor installed on their devices, according to the report.

Alternative applications

Hacktivist groups and pro-democracy organizations in other East and Southeast Asian countries have promoted other viable applications on social media and other outlets, said Anissa Wozencraft, a threat intelligence analyst and co-author of the report.

Offline messaging app Bridgefly, which gained popularity during the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests last year, was downloaded more than 1 million times shortly after the country’s military seized power and disrupted internet usage. The app is based on Bluetooth and allows users to communicate without internet connections through the use of mesh networks.

Signal, Briar, TailsOS, and the Brave Browser have also been touted by hacktivist groups, while forum users have promoted the Mysterium Internet BlackOut Toolkit—a resource to help users unblock websites and applications, anonymize internet activities, and keep open communication channels when networks are shut down, according to the report.

Unsurprisingly, VPN demand skyrocketed in Myanmar following the social media ban—Top10VPN, a Britain-based digital security advocacy group, reported a 7,200% increase in local demand for VPNs in early February.

A rising trend

The fact that hacktivist groups and pro-democracy organizations were able to quickly roll out a playbook to bypass internet censorship and outages highlights how authoritarian governments around the world are increasingly tightening their grips on internet access as a tool for control.

The #KeepItOn coalition and Access Now—a nonprofit focused on defending digital rights—documented at least 155 internet shutdowns in 29 countries last year. India topped the list in terms of total shutdowns throughout the year—109 in all—but several countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia Pacific also imposed internet cutoffs.

Although these past shutdowns have helped people establish a playbook for dealing with them, the report from the two groups highlights how governments are also learning to block evasion efforts.

“Governments often do not stop at shutting down the internet. They go further and make sure citizens do not have alternative channels of communications or a way to circumvent state blocking and censorship,” according to the report. “Countries… have banned the use of VPNs and other tools for security, anonymity, and circumvention, such as those from the Tor Project, or they have specifically blocked VPN providers and the Tor site, as Belarus has done since 2015.”

Adam Janofsky

is the founding editor-in-chief of The Record from Recorded Future News. He previously was the cybersecurity and privacy reporter for Protocol, and prior to that covered cybersecurity, AI, and other emerging technology for The Wall Street Journal.