Fear and Covid in Las Vegas: Pen testing Hacker Summer Camp’s mask policies

I haven’t always claimed the title, but I’m a hacker. I can do some lockpicking and SQL injections, but my primary toolset is journalism—my job is fundamentally to learn about systems, discover where they might be vulnerable, and then report that information to the public in line with the hacker ethic, often with the hope that someone will patch the problem.

At "Hacker Summer Camp" this year, my main investigation was penetration testing masking compliance and enforcement systems as both Black Hat and DEF CON brought back in-person events during a surge of the highly contagious Delta variant of Covid-19. But the chaos I encountered on the ground in Las Vegas raised serious questions about the health precautions in place this year and just how much we can trust each other when compliance is directly tied to physical community safety.

Compliance is always tricky because it relies on humans and we make mistakes—myself included. That’s why rules typically come with enforcement mechanisms and reporting systems that can help us understand actual compliance rates. Unfortunately, my testing found breakdowns across the board when it came to masking in Las Vegas.

When I landed at McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas on Aug. 2nd, the state was reporting more than 1,000 new cases a day and Governor Steve Sisolak (D) had already rolled out a new emergency mask mandate requiring face coverings in indoor public places regardless of vaccination status in high-risk areas. The order featured very limited exceptions, such as for when a person was “actively eating or drinking.”

Although I am vaccinated, without the mask mandate I probably would’ve cancelled my trip—as several prominent security researchers did. However, in consultation with journalism peers and health experts, I decided I was comfortable going to cover the effect of the crisis on the conferences if I followed strict safety measures that would limit the risk to myself and the local community.

And that community is at risk—especially frontline workers who kept the resorts and restaurants operating during the conferences. Culinary Workers Union Local 226 and Bartenders Union Local 165, which represent 60,000 workers around Las Vegas and Reno including those at the venues hosting Black Hat and DEF CON, told The Record that 146 members or their immediate families have died and 1,508 have been hospitalized due to COVID-19 since March 1, 2020.

Unfortunately, the mask mandate was much more theoretical than practical on the ground. Travellers masked haphazardly (if at all) while crowded in transit within the airport and to the rental car center. Many appeared not to be aware that current regulation called for masks for everyone indoors. Some were hostile when asked to cover their mouths or noses.

Once in my rental car, I committed to picking up essentials and treating the situation as a biohazard. Then I checked into the Mandalay Bay—the massive aquatic-themed complex hosting Black Hat—which would be my basecamp between doing limited in-person coverage and virtual coverage I jokingly dubbed “#RoomCon.”

My room overlooked the Mandalay “Beach,” a waterpark built into the desert featuring a lazy river, wave pool, and bar. When it was packed with outdoor concerts over the weekend, my stomach sank as I recalled a June Las Vegas Journal-Review report about eight local vaccinated healthcare workers with breakthrough Delta variant infections after attending a pool party.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance released in late July, just before Nevada’s new mask rules, noted that early research suggests breakthrough infections among vaccinated people are very rare. However, those breakthrough infections could still contribute to community spread—especially in high transmission areas with low vaccination rates.

Areas like Las Vegas.

With that in mind, my full pandemic aesthetic for indoor spaces was a cyberpunk parody involving fitted goggles and a half face respirator customized with a “Survive!” message layered over fitted N95 masks. Even with the Delta variants' increased infectivity, experts say N95 masks provide more protection than alternatives like cloth masks or bandanas.

My look was practical, but also performance art—a stark visual reminder to others that I was taking my health seriously and they should too. And it definitely got attention. The first comment about it was from a boy who looked around ten years old while I got lost looking for the Mandalay check-in.

“Your mask is cool!” he leaned in to tell me while pulling his thin, blue, paper mask down to dangle below his chin.

I said thank you, then asked him to pull his own up.

Black Hat

Black Hat was always going to be the riskier of the two conferences from a health perspective. Organizers never required proof of vaccination to attend, unlike DEF CON, and the conference only announced it would require masks after the move was forced by the Governor’s directive.

The resort provided masks and hand sanitizer at signs throughout the property reminding visitors of the local masking requirement. But compliance was poor, especially in the casino and other public areas.

I had my first hostile encounter with a Black Hat attendee over masking near the restaurants inside the public resort area on the night of Aug. 3rd before I had a chance to pick up my press badge. As I was bringing luggage in, I noticed a badged attendee, mask down and engrossed in a phone call while sitting a dozen feet past one of the “masks required” signs.

I approached and introduced myself as a reporter covering the conference interested in talking to them about masking compliance. The person—who appeared white, male, and in their 40s or 50s—became visibly agitated, argued that no one was nearby, and tried to hide their name badge.

As I walked away, they yelled after me that I "better not write about this.” (A threat that is almost sure to make a reporter “write about this.”)

Anxious, I made my own compliance error the next morning after I headed over to the Business Hall—the main showroom full of vendor booths—for what was meant as a quick scan of the room before beginning coverage in earnest. I immediately noticed that a presenter at the largest vendor booth directly in front of the entrance was unmasked while speaking in front of a small crowd. I started documenting this and other mask violations with my camera. (Black Hat’s press policy prohibits taking photos of attendees without their permission. I apologized to organizers for my error, and The Record is not publishing photos or videos captured without consent).

When I first approached the booth staff about the maskless presenter, I was told it was an error and that future speakers would be masked. But when I asked the speaker themselves afterwards, they insisted that they did not need to mask due to a conference policy and asked me to leave the booth. I complied, taking a round of the conference floor where I saw many more masking violations from vendors and attendees, before documenting a subsequent presenter in the same spot also unmasked from outside the booth space.

The first presenter pointed me out to conference security, who then pulled me aside. I explained I was media documenting violations of local health code and had complied with the prior request to leave the booth. I also pointed out the maskless person directly behind us, but saw no action taken.

Instead, security seemed more concerned about me documenting public health violations and harming vendor relations than the violations themselves. I followed one to the press room, I apologized for my mistake, then explained to conference representatives about the apparent vendor violations of health regulations.

The press representative told me that vendors should know better and they would follow up. Then I asked for guidance on how members of the media or attendees should report or provide evidence of public health violations without risking a hostile encounter, like the one I had with an attendee the night before. The press contact didn’t know, but said they would try to find out and get back to me.

I followed up—several times—about that question and others, including who was supposed to do what in terms of mask enforcement, but received no response.

After seeing that lack of masking in the conference areas, I cancelled almost all my in-person Black Hat plans—keeping one outdoor meet-up related to a long-term reporting project.

As the more business-oriented of the Hacker Summer Camp conferences, Black Hat is known for lavish parties with open bars—networking events that can be more important to deal-making than the official conference schedule. And that heavy-drinking culture continued despite the pandemic, appearing to contribute to the rampant masking violations across the resort.

I was on the list for one such party hosted by a cybersecurity firm at a restaurant at the Mandalay, but skipped it after walking by and deciding the mask(less) situation wasn’t worth the risk.

(Disclosure: Recorded Future, which owns The Record, had a presence at Black Hat and hosted an indoor happy hour event, which I did not attend.)

While bringing carry-out back to my room later, I observed several large groups of a dozen or more badged Black Hat attendees roaming around the public areas of the resort and casino, maskless, and most without food or drink in hand.

I covered the rest of Black Hat from my room or the Mandalay’s Beach in the early morning if I could find an isolated spot before the crowds rolled in.

DEF CON

I went into DEF CON at Bally’s and Paris on Aug. 6 cautiously optimistic, both because organizers had taken the public health risks more seriously than Black Hat while planning—including requiring proof of vaccination—and because the community-oriented nature of the conference seemed less likely to put commercial pressures above public health.

I wasn’t alone. Jayson Street, a security speaker who is a DEF CON Groups Global Ambassador and has done trainings with Black Hat, told me he felt more secure at DEF CON.

“Having that vaccinated bubble is a big deal,” he said.

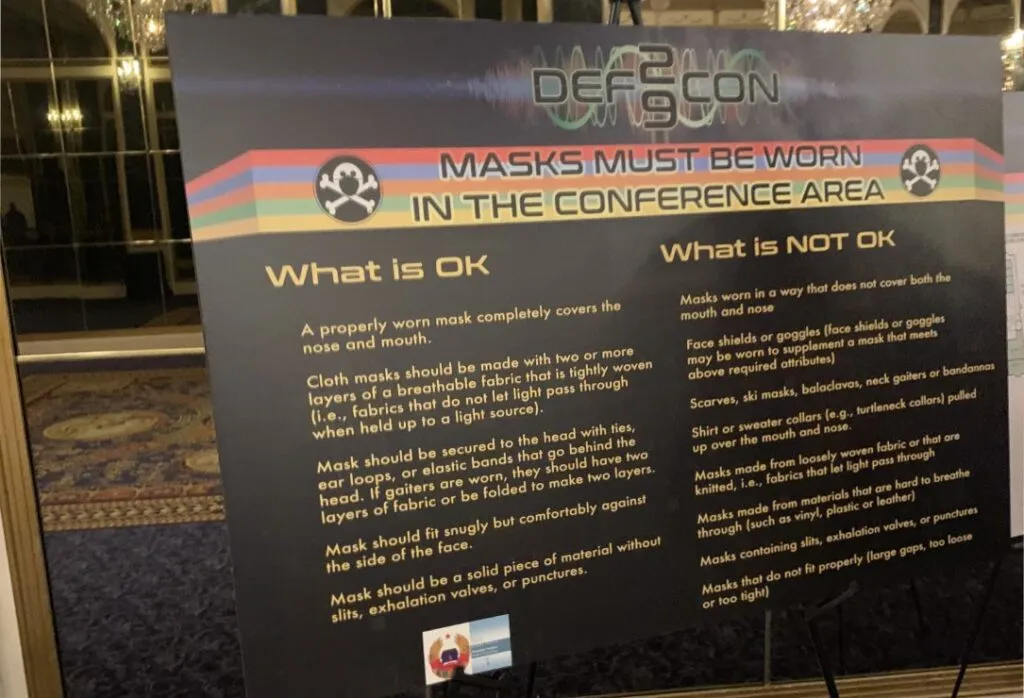

My initial experience was also positive: Before getting your badge, you had to check in with a third-party and get an iridescent wristband by showing proof of vaccination with time for full incubation and having it visually verified against your ID. There were conference specific signs, not only about the masks being required, but outlining which specific kinds of masks did or didn’t meet conference standards—no to bandanas and gaiters.

But while these policies were thoughtfully conceived, the conference struggled with actual masking compliance and enforcement once pressed.

I started with the room featuring the Car Hacking Village because it was near check-in and immediately spotted a person behind the tables with a non-compliant bandana-style mask down around his neck. I returned to Inhuman Registration (where the press checks in) and asked what I should do—explaining that I previously encountered hostility when approaching people about not masking.

The volunteer, or “Goon” in DEF CON terms, told me that I should ask nearby Goons and they would approach unmasked or improperly masked attendees and remind them about the requirement. The situation would be escalated to hotel security if they didn’t comply, they added. Then I showed them the unmasked person, they reminded them, and the person re-masked.

Problem solved—at least temporarily.

I kept testing by pointing out mask violations to Goons in that same room. While masking was far more consistent than at Black Hat, I could still find at least one violation almost everywhere I turned. And the system worked great the first few reports. Once, a conference attendee and I both approached two Goons with masking concerns and they hesitated, but helped.

But while reporting my fourth person, I encountered a bug. When I approached a Goon about an unmasked person, they fought with me about it—telling me they could not approach and ask the person to mask, only hotel security could. I said that wasn’t what I was told, but they continued to argue until the unmasked person left. The Goon walked away after I asked them to follow me to Inhuman Registration to verify the policy.

At Inhuman Registration, I was shuffled between several Goon contacts trying to confirm and get a written copy of the policy, at one point having to ask them to remind a person on the phone near the vaccination check-in to mask.

I didn’t get a clear answer or a written policy until the next day, when DEF CON press lead Melanie Ensign confirmed that Goons were expected to politely remind attendees to mask, but refer the issue to hotel security if they did not comply.

“Your concerns should never have been dismissed,” Ensign wrote, apologizing. “That was wrong. It's the responsibility of our Goons to remind attendees of our policies, especially when it comes to personal safety.”

For the rest of my time on site on Aug. 6, I adjusted my strategy to see how the conference would handle repeat masking offenders. Unfortunately, I found a very easy test case for this issue because the same person I reported the first time was unmasked almost every time I checked the Car Hacking Village—typically to vape or talk. Within three hours I reported them five times to three different Goons at Inhuman Registration. After the fourth report, I was told they were being referred to hotel security—and that I wasn’t the only person who had reported them.

When I arrived on site the next day, the person was there too—unmasked. I approached the person, who declined to identify themselves, as well as the person in charge of the Car Hacking Village, for comment on the repeat masking violations and warnings by Goons that I observed.

Both claimed it had happened only once, even after I noted that I had personally observed it multiple times due to my own reports the day before. They also said they had not had any contact with hotel security. DEF CON did not directly respond to my questions about whether hotel security was actually contacted in this situation, as I was informed would happen. The Car Hacking Village did not respond to a request for comment.

After the repeated masking failures and the Car Hacking Village associates’ apparent attempts to mislead the public through their comments, I no longer trusted these nodes in the network. And here, I had another personal compliance failure: I took a few general photos of the area that included the masking violations at the Car Hacking Village in the background to show organizers that the issue remained unresolved—a technical violation of DEF CON’s (often ignored) photo policy that I self-reported.

The Record is not publishing any photos taken by this reporter at DEF CON without express consent of subjects. However, the Car Hacking Village’s sponsor posted a picture promoting their involvement that features the same individual I repeatedly reported as unmasked… unmasked.

After my second report of the repeat Car Hacking Village unmasker on Aug. 7, I had a sit down with Goon Security who assured me they were taking that situation seriously, but still investigating the incident they later confirmed where a Goon refused to ask a person to mask the previous day.

I left that meeting to try to actually enjoy some of the conference, only to run into a Goon openly violating the masking policy to vape in a conference hallway.

After I approached the Goon, they confirmed they were unmasked to vape, which they claimed was acceptable under current health regulations. I asked the other Goon with them to identify themselves by their handle (the nickname Goons use at the conference) so I could include them as witness and they declined to share it—another violation of conference policy—and walked away.

The one who refused to identify themself (falsely) accused me of trying to take their photo as I went to pull up the contact information for the Goons I just met with on my phone. Then I saw a Goon associated with the Security Team and had them call it in, but noted I needed to leave shortly to make a pre-scheduled meeting—a documentary shooting where I would wax poetic about journalism as a form of hacking.

The pair of Goons involved in the masking and identification compliance incident then walked back into sight and I pointed them out. In response to the call to Goon Security, more than a half-dozen mostly male-presenting Goons surrounded me. The one leading the questioning wouldn't let me leave until one of the Goons from my prior meeting showed up and confirmed that I was already in touch with them about reporting masking violations.

I felt like a security researcher being blamed for pointing out an exploit in code.

Compliance and Community

By the end of my reporting trip, I was burnt out from feeling like I was the only one who was taking masking violations seriously.

But I wasn’t actually alone in that.

I stayed in touch with the person who approached Goons at the same time as me about masking violations, who requested to be identified by their handle diskcraft.

They described a similar feeling of helplessness about the lack of masking by fellow conference goers and the public. At one point, diskcraft observed DEF CON attendees in a conference area talking unmasked for ten minutes, they wrote to me after the event. I personally never observed a Goon remind someone to mask without asking for the intervention, including several cases where I noted violations to Goons without directly requesting help. (Street told me about one instance where a Goon reminded him to re-mask after drinking at an official party.)

Diskcraft said they saw basically zero masking enforcement, even as they raised the problem with the venue directly.

“I talked to the hotel manager Sunday morning and while we were talking people just walked through the door and lobby maskless,” they wrote.

Hotel employees I spoke to during both conferences on the condition of anonymity told me they were severely understaffed and not expected to confront maskless guests.

“I’m already risking getting infected by coming into work, I’m not going to risk getting into a fight,” one resort staffer said.

That made total sense to me after my own experiences—as did the reluctance I observed from some Goons to remind attendees about masking, which was often openly violated in front of them.

This was obviously not part of their regular duties and conflict is stressful.

“DEF CON staff are not intended to be bouncers, but are assigned to help attendees find information and activities—and to contact the hotel when needed,” DEF CON’s Ensign wrote. However, she added that unmasked attendees were included in the list of potential conflicts to escalate to venue security this year and the conference “had an explicit agreement with the hotel for them to handle escalations.”

Caesars Entertainment, which owns Bally’s and Paris, and Mandalay Bay’s parent company MGM Entertainment did not respond to The Record’s requests for comments about masking violations or how they enforced masking policies.

A notice from the Nevada Gaming Control Board, which oversee casinos in the state, said after the Governor’s masking directive that its licensees “shall ensure that all employees, patrons, and guests properly utilize face coverings,” but only included one specific requirement—that casinos “have dedicated signage throughout its establishment notifying patrons where face coverings are required.” This was present at both conference sites.

The Board declined to comment on how many complaints it has received about masking violations since the new mandate or if any licensees have been subject to penalties for violations.

It’s also hard to track the actual health outcomes of the conferences in attendees and the community, although DEF CON’s Head of Security has been tweeting out updates suggesting at least a handful of known infections among attendees at both events.

Current coronavirus scorecard from summercamp (that I know of) Blackhat, 6. DEFCON, 3. One of the DC counts is a confirmed BH/DC crossover. I’ll update numbers as people check in/provide further info. #DEFCON #DEFCON29 #Blackhat

— Marc Rogers (@marcwrogers) August 16, 2021

Despite this year’s challenges, diskcraft remains a DEF CON fan. “My feeling is that I love it and don't want to hurt it—but that people need to adhere to codes of conduct,” they wrote.

And I found things to love too—mostly interactions with other people who leaned into the masking requirement.

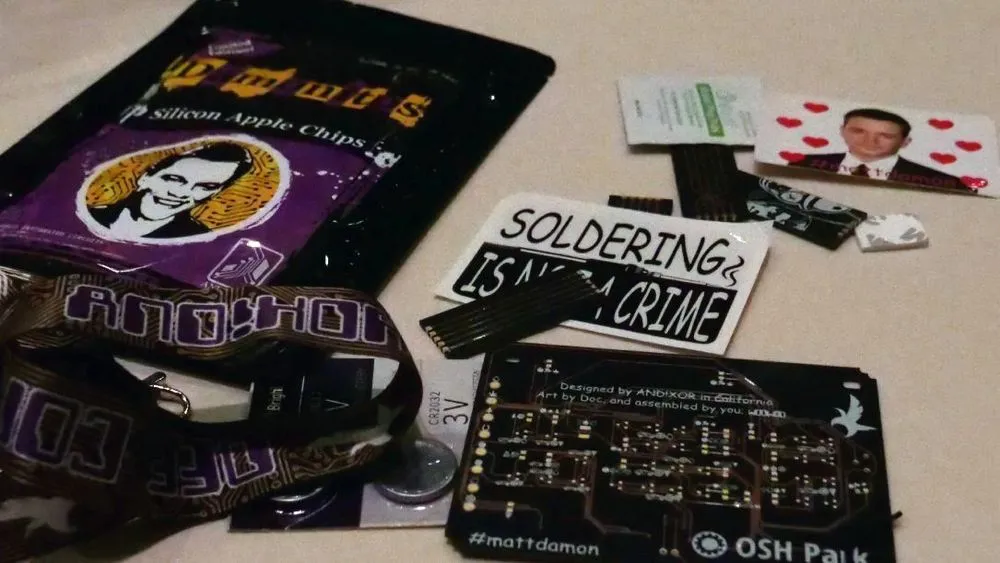

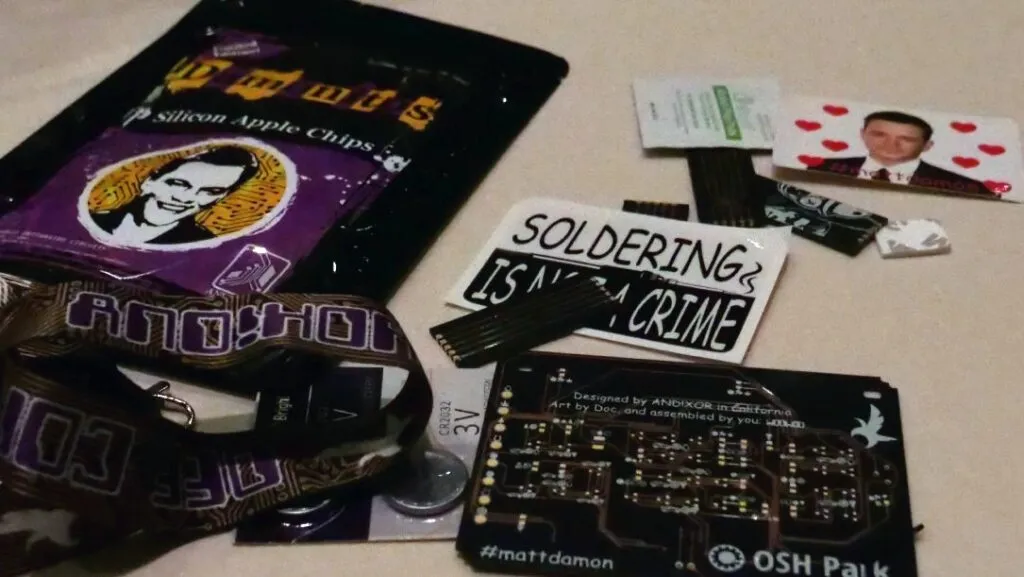

The AND!XOR crew, which designs alternative DEF CON badges, rewarded me with a DIY “Damonitos” soldering kit badge after I complimented their iridescent face shields and remembered the name of a Matt Damon movie. Then we talked about how they had to change their plans due pandemic electronic shortages—making something much simpler than their original design, but creating an experience to get people to explore hardware hacking.

I also loved talking to Erick Hammersmark about his elaborately designed respirator, which featured pressure detectors that made built-in LEDs change color with his breath. And in a quiet moment, I told a pair of Goons in the Memorial Room about the recently passed friend who introduced me to DEF CON while crying and pinning photos of him to a provided display board.

These community experiences, more than anything, drove many to show up despite the risks.

“It’s been too long and we needed this opportunity to get together after the isolation,” Street told me. For him, and many other longtime attendees (including myself) who don’t always fit into the mainstream, DEF CON is their chance to connect with their chosen family, he added.

“I’m so grateful for it,” Street said.

Many of the people I was excited to see stayed away due to the pandemic—and my relationship is more complex because I both identify as a member of the community involved in DEF CON and cover it. But even as a member of the press, I pay $300 to attend just like regular attendees. Although I was grateful DEF CON organizers seriously engaged with me about the problems, their shifting responses to me pointing out public health vulnerabilities left me feeling unsafe and gaslit.

I went to check on the repeat mask offender at the Car Hacking Village one last time before leaving on Saturday and saw them unmasked for the ninth time—vaping and talking with the Car Hacking Village organizer from before.

I reported it. Again.

The Goon who was handling my report asked me to wait, left and apparently dealt with it, then returned to tell me it was “an accident” and the person “didn’t realize” it was down.

Exhausted and defeated, I asked how many times someone needed to be reported for them to be considered untrustworthy—trying to explain that it wasn’t that I wanted to see anyone punished or ruin their CON, but that it didn’t seem like there was a system.

The Goon didn’t know, but was clearly stressed by the whole situation too and I asked them to do an on-the-record interview about it. They said the conference was planning to offer me interviews with specific people later.

When I requested those interviews via email, they were not offered. When I asked how many reports they logged from me personally so I could compare it against my own notes, Ensign acknowledged they didn’t have a way to track that. When I asked if they tracked how many times Goons had received reports about people unmasked and related data, they referred me to the public Transparency Report released during closing ceremonies.

Here’s the transparency report I released after #DEFCON29 as a reminder you can find the previous #defcon reports on @defcon here https://t.co/kEeEhC7WtD pic.twitter.com/TbWntAAmnh

— Marc Rogers (@marcwrogers) August 12, 2021

That report showed two people removed from the conference for not masking, two people removed by security from the vaccination check area, and approximately 25 people turned away for not having proof of vaccination. DEF CON declined to share further details about the removal instances referenced.

Given those statistics, I would think everything went smoothly—at least, if I didn’t know about all the compliance issues not reflected in the data. But this type of summary doesn't necessarily show what happened—it shows what was reported. For example, the report lists three photo policy violations, but a quick search of Twitter shows evidence of many more.

There’s also little incentive to report things if you don’t feel like the report will matter.

From my own personal experience, I know there was harassment at the conference not reflected in the initial report—including sexual harassment and hostility towards those requesting other attendees mask. I’ve been mocked online for reporting on this topic and I expect more harassment after publication. (Editorial note: The Record chose not to include specific Goon handles or identify those observed unmasked by name in this story to avoid contributing to harassment.)

In fact, diskcraft requested I use their handle rather than their name in my reporting due to fears of blowback.

“I don’t want to get attacked. I have been pretty outspoken to people who are maskless,” diskcraft emailed me. “Who knows how mad someone could get,” they added.

And here, I need to note one last personal compliance failure: I didn’t report an incident of verbal sexual harassment I experienced at the conference while asking about masking until this week—in part, due to pervasive harassment faced while covering the conference years earlier but also because the general lack of enforcement around masks didn’t make me feel confident any report would be taken seriously.

On my way to my rental car from my final report about the repeat unmasker on Aug. 7, I saw another badged DEF CON attendee unmasked and had a split-second exchange after asking about it. They remasked while declining to comment with a demeaning (and very unoriginal) joke describing me as a “honey trap”—a sexuality-based security threat, referencing my female-presenting body—and disappeared into the crowd.

I kept it together until I got to my rental car, cried in frustration, then covered the final day of the conference from my hotel room and took some time off.

DEF CON’s Ensign thanked me for reporting the harassment and said they are investigating.

(Correction: An earlier version of this story included the incorrect dates, but correct days, for events at DEF CON.)

Andrea Peterson

(they/them) is a longtime cybersecurity journalist who cut their teeth covering technology policy at ThinkProgress (RIP) and The Washington Post before doing deep-dive public records investigations at the Project on Government Oversight and American Oversight.