FDA pushing for medical device cybersecurity funding, regulations

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is pushing for Congress to provide more funding and support for efforts to address the cybersecurity protections of medical devices.

The rise in devices used by healthcare facilities over the last decade has led to a corresponding increase in the number of vulnerabilities found – affecting everything from infusion pumps to autonomous robots.

The FBI warned in September that hundreds of vulnerabilities in widely-used medical devices are leaving a door open for cyberattacks on hospitals and healthcare facilities, both of which have become prime targets for nation-state hackers and ransomware gangs.

The FBI specifically cited vulnerabilities found in insulin pumps, intracardiac defibrillators, mobile cardiac telemetry, pacemakers and intrathecal pain pumps, noting that malicious hackers could take over the devices and change readings, administer drug overdoses, or “otherwise endanger patient health.”

“Cyber threat actors exploiting medical device vulnerabilities adversely impact healthcare facilities’ operational functions, patient safety, data confidentiality, and data integrity,” the alert said.

The FBI added that vulnerabilities typically stem from device hardware design issues and software management. The problems are exacerbated by a lack of embedded security features in devices and an inability to upgrade those features.

Medical device cybersecurity experts were outraged in September when, despite these concerns, Congress passed a short-term continuing resolution through December 16 that did not include previously introduced cybersecurity measures requiring developers to create processes for identifying and addressing security vulnerabilities and threats, and to include software bill of materials (SBOM).

One of the more important elements previously in the measure would have required any manufacturer issuing premarket submissions of a cyber device to include relevant information showing cybersecurity protections have been implemented with reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness – effectively proof that a device meets cybersecurity requirements.

Thomas Pace, CEO of device cybersecurity firm NetRise, said it was unclear why the rules were left out but noted that there may have been political pressure from device manufacturers and complaints that the requirements would be too costly or onerous.

“The main risk here is a lack of even a baseline of protection that can be validated in any way. This is unacceptable for prescription drugs the FDA approves, so why not the devices that are also healing patients as well?” he said.

Pace explained that most manufacturers of any software, hardware and firmware are not where they should be in terms of disclosing vulnerabilities, adding that medical devices are some of the more problematic devices to patch, update and maintain.

He explained that the measure around software bill of materials would have been particularly helpful because understanding what components make up those devices would allow defenders to know what to monitor and assess for risk.

“This is what an SBOM can provide, what one does with that data after an SBOM is created can address many issues that exist in cybersecurity today,” he said.

A spokesperson for the FDA told The Record that while the short-term continuing resolution did not include many of the cybersecurity measures originally included, it did reauthorize medical product user fee authorities – a program started in 2002 that forced medical device companies to pay fees to the FDA when they register their establishments and list their devices with the agency.

The fees, according to the FDA, allow them to “increase the efficiency of regulatory processes with a goal of reducing the time it takes to bring safe and effective medical devices to the U.S. market.”

The short-term continuing resolution included a full five-year reauthorization of the program, according to the FDA, “in addition to other user fee agreements.”

“In order to avoid a delay in user fee reauthorization, we understand Congress determined that other ‘policy riders,’ such as legislation clarifying cybersecurity for medical devices, would need to be considered as part of year-end omnibus legislation before the continuing resolution expires,” the spokesperson said.

“We hope that Congress is able to reach agreement on the other important policy riders as part of the final year-end package.” The FDA spokesperson added the agency is hopeful that its request of $5 million for a medical device security program is approved as part of FY2023 appropriations legislation.

Grant Geyer, chief product officer at operational technology cybersecurity firm Claroty, said the measures were removed from the bill as a result of congressional negotiations with the private sector and noted that this was a missed opportunity given the increased connectivity of medical devices and the cyber risks involved.

According to Geyer, the number of vulnerabilities will only increase as software becomes more complex and more medical devices are digitized.

Geyer expressed support for another piece of legislation to address this issue, called the PATCH Act – a bill requiring premarket applications for medical devices that include software or are connected to the internet to include information relating to cybersecurity, including plans to monitor for cybersecurity risks and address vulnerabilities through regular product updates.

The bill was introduced in March by Rep. Michael Burgess (R-TX) but stalled in the House.

While Geyer acknowledged that manufacturers want to develop cyber safe clinical devices, the cybersecurity changes needed “can either be inherently adopted by the medical device manufacturers, or mandated by legislation,” he explained. Transparency, he said, is a critical component to the cyber safety of IoT devices.

“Software vulnerability awareness and disclosure isn’t moving fast enough, which represents a growing risk to patient safety. The PATCH Act contained a provision requiring the medical device manufacturers to establish a coordinated vulnerability disclosure process, which would have obligated them to establish the structure, process, and team to engage with third parties and deliver safe and secure medical devices,” he said.

An interconnected web

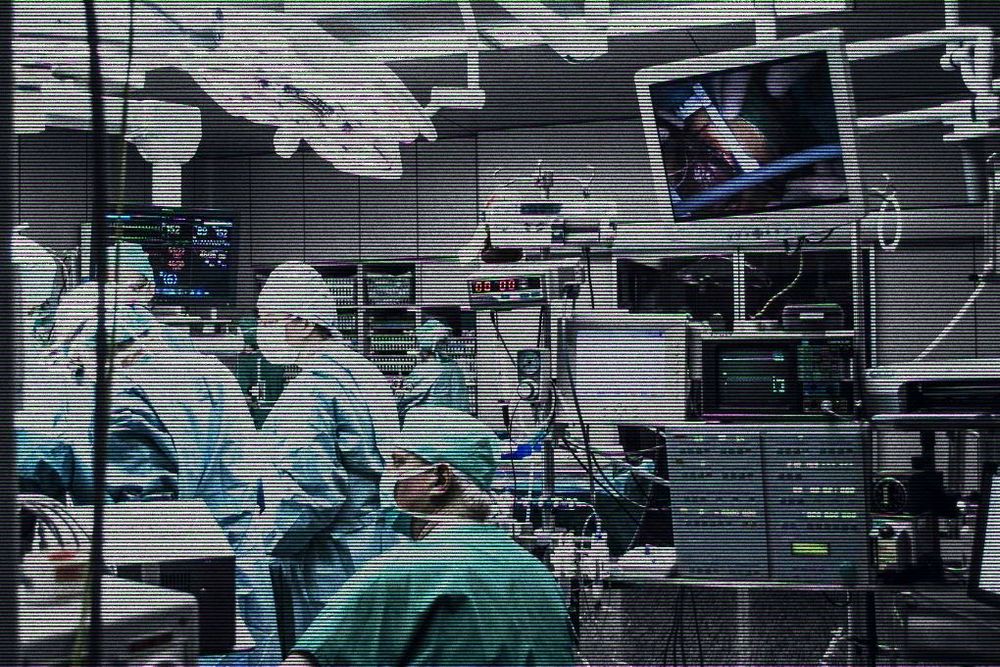

According to Ordr CEO Jim Hyman, a given network can include tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of devices.

A single patient bed on average has 10-15 connected devices, he noted, adding that these devices increase the attack surface because they are not always designed with security in mind, and often run outdated operating systems.

Hyman said tools cybersecurity experts traditionally use to scan for vulnerabilities cannot be used on medical devices because they impact how the tools operate. And because of how many devices work, you cannot put traditional security programs on them like one would with a laptop or smartphone.

"Many healthcare organizations are recognizing the importance of medical device security. However, in order to implement a medical device security program, organizations need budget/funding, along with the resources and process to make it successful,” he said.

“While all of this may seem daunting, note that many of the leading healthcare systems like Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic have been implementing their medical device security program for several years now, and have matured from foundational use cases such as asset inventory and vulnerability management to Zero Trust segmentation.”

Establishing cybersecurity norms in the industry would have upfront costs, however. A report from Moody’s Investors Service in November found that if medical device cyber risk regulation eventually becomes law, it would likely raise the cost of product development for medical device companies, or lengthen any regulatory review processes at the FDA.

“However, we believe the value of new cybersecurity measures would pay benefits, that, over time, would outweigh their costs. Over time, product innovation that delivers tangible value to patient care and outcomes will likely provide profitable long-term growth opportunities for the medical device industry that will offset any incremental costs associated with rising investments in IT security or additional regulatory reviews,” they explained.

Last month, the FDA partnered with non-profit MITRE to publish an updated Medical Device Cybersecurity Regional Incident Preparedness and Response Playbook – a document designed to help healthcare organizations prepare for cybersecurity incidents.

The updates included an emphasis on the need for all hospital staff to be involved in the cybersecurity process – including clinicians, healthcare technology management professionals, IT, emergency response, and risk management and facilities staff.

The document also added new resources around how healthcare facilities can handle extended downtimes from cybersecurity incidents and prepare for medical device cybersecurity incidents, including ransomware.

The increased attention from the federal government on hospital security follows brazen attacks by ransomware groups who have wreaked havoc around the world, targeting hundreds of healthcare facilities and crippling services for millions of people.

Oscar Miranda, CTO for healthcare at Armis, has spent 18 years implementing controls for securing and protecting the privacy of electronic health information at healthcare giants like Kaiser Permanente.

Miranda said a recent Forrester Consulting study found that 63 percent of healthcare delivery organizations have experienced a security incident related to unmanaged and IoT devices and 64 percent of healthcare delivery organizations estimate that at least half of all devices on their network are unmanaged or IoT devices, including medical devices.

“Hospitals rely on an array of connected devices to monitor patients and provide critical care,” he said.

“As such, these assets have become essential to the patient journey, but are the weakest security link in healthcare and serve as an attack vector for ransomware.”

Jonathan Greig

is a Breaking News Reporter at Recorded Future News. Jonathan has worked across the globe as a journalist since 2014. Before moving back to New York City, he worked for news outlets in South Africa, Jordan and Cambodia. He previously covered cybersecurity at ZDNet and TechRepublic.