FBI, DOJ say less than 25% of NetWalker ransomware victims reported incidents

Just one fourth of all NetWalker ransomware victims reported incidents to law enforcement, according to officials from the FBI and Justice Department who led the takedown of the group.

Ryan Frampton – a member of the cyberaction team at the FBI’s Tampa Division – and Carlton Gammons – the lead prosecutor for the US Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Florida – spoke at length about their work shutting down the infrastructure of the NetWalker ransomware at the RSA conference on Thursday.

The FBI and DOJ were able to obtain a trove of information on the group after seizing NetWalker’s backend servers in Bulgaria during an investigation throughout 2020.

Frampton said just 115 NetWalker victims filed reports with the FBI’s IC3 center or their local FBI office. But that number is dwarfed by what they found on the NetWalker servers used to host their TOR site.

The servers contained more than 1,000 “builds” – different versions of the NetWalker ransomware customized for each victim based on an analysis of already-breached systems.

“We've fully identified over 450 victims in this investigation, but only 115 actually filed a report. There were 1,500 builds, so the real number of victims in this case was somewhere between 400 and 1,500, and we’re never going to know exactly how many there actually were,” Frampton said.

“It is important to note that only a quarter of the ones we have fully identified actually filed a report. Those victims that filed a report said they paid $6.7 million dollars. But if you look at the blockchain research and the information that we obtained from the backend server, Netwalker actually extorted nearly $60 million. So whatever numbers you see in the public, it's probably way higher than that.”

Only 15 victims told the FBI they paid a ransom but the actual number is more than 200, according to Frampton, who noted that the highest ransom demanded was $12 million and the highest actual payout was $3 million.

The average ransom demand was $481,000 while the average actual payment was about $196,000. It typically took Netwalker affiliates about nine days from the time they created the specific build to when a victim would pay a ransom.

Frampton told the audience that the investigation into NetWalker began in late 2019 after a victim reported an incident to the IC3 center.

It ramped up significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, when NetWalker affiliates made a name for themselves attacking healthcare entities like hospitals, health departments and medical research institutions, both domestically and abroad, throughout March and April 2020.

Most victims waited about 11 days from the time of infection to report a ransomware attack to the FBI, according to Frampton.

Gammons said that from their investigation of the group, they found that 10% of all ransoms went to the developers of the ransomware and 80% was given to the affiliates who actually conducted the attack.

Victims were sent a link to the group’s TOR site with a code specific to them and from there, victims could communicate with the group, receive the ransom demand, and learn how much time they had before data was leaked.

“Initially, if you did not pay NetWalker, they would just not give you access to your data, But as time went on, it changed to ‘if you did not pay I'm going to publish your data,'” Gammons said.

“I can tell you, we talked to companies and they did not want their shareholders, or customers to know that they were victims of ransomware. They'd rather do whatever they're going to want to do internally rather than let anybody find out that they've been victimized.”

Gammons went on to explain that the access they gained to NetWalker’s servers provided them with a deluge of information on the group’s internal operations. The group kept documents on each victim that had an executable file, a powershell script and a text file that identified the victim.

They “had essentially everything you need to commit a ransomware attack and they were customized to each victim,” Gammons explained, adding that for some victims, they would have 2-3 builds.

“This was really important because it helped identify who the actual victims were. Only a fraction actually reported them. The files had invoices showing how much people were quoted for their ransom and how much they actually paid,” he said.

“It had Bitcoin addresses, Jabber handles, decryption keys. There were dozens of affiliates.”

Frampton added that with the access they gained to the decryption keys, he was able to reverse engineer it to create a decryptor and provided more than a dozen victims with a decryptor utility that allowed them to restore their encrypted data.

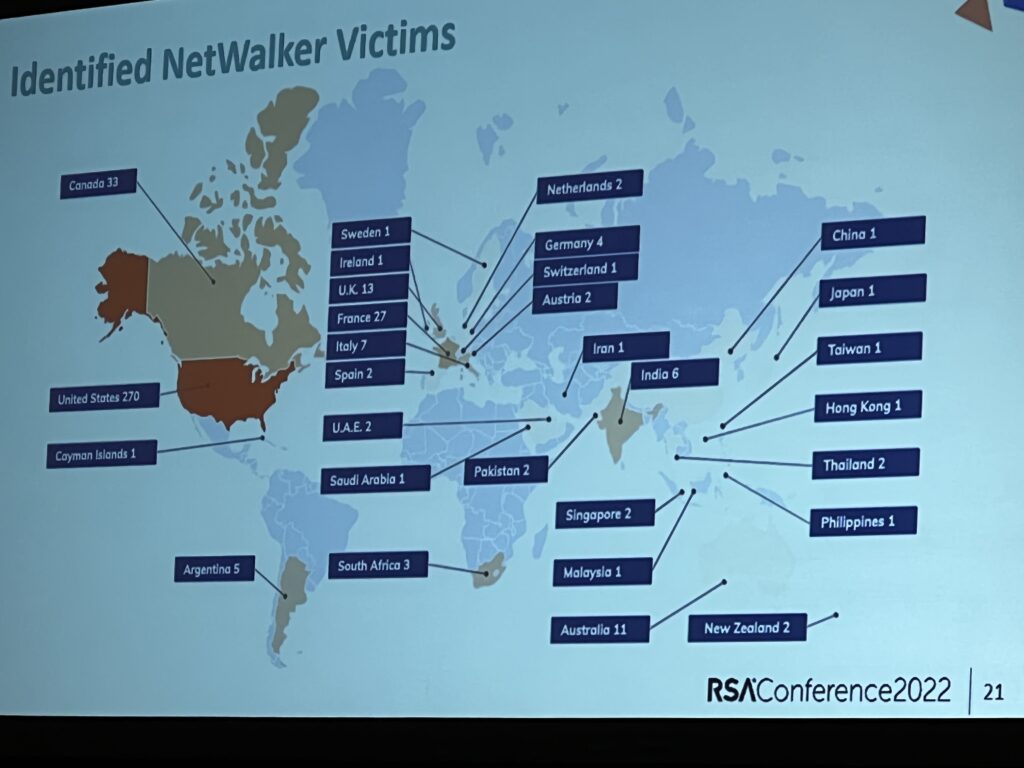

They found more than 10,000 messages from the group's members and discovered that NetWalker attacked organizations “on every continent except Antarctica.”

Gammons said NetWalker attacked 270 organizations in the U.S., 33 in Canada and dozens of others in Hong Kong, Thailand, Sweden, France, Italy, Spain and even the Cayman Islands.

This unparalleled access is what led them to Sebastien Vachon-Desjardins, a 34-year-old from Gatineau, Quebec who they identified as the most prolific NetWalker affiliate.

In February, he was sentenced in Canada to seven years in prison and was extradited in March to the U.S., where he will face multiple charges related to his alleged participation with the ransomware group.

Gammons said he is currently being held in Tampa.

The NetWalker ransomware affiliate arrested in Canada last year pleaded guilty and was sentenced to seven years in prisonhttps://t.co/plIIf1NGCi pic.twitter.com/8aboCbgm7Q

— Catalin Cimpanu (@campuscodi) February 8, 2022

Gammons noted that Vachon-Desjardins was responsible for 157 builds and made 1,595 Bitcoin from ransoms – more than $4.5 million.

Surprisingly, Gammons explained Vachon-Desjardins was working for the Canadian government as an IT employee while conducting ransomware attacks on behalf of NetWalker.

After collecting troves of information on the group and identifying Vachon-Desjardins, Gammons said the Justice Department was faced with the dilemma of taking action or waiting.

“We have basically the infrastructure that's letting the NetWalker ransomware work. We've identified the leading affiliate. We can do a law enforcement action, right? We can arrest somebody. We can take down the servers but that will take away our ability to continue to conduct the covert investigation,” Gammons said.

“So the investigative team got together and we discussed the pros and the cons. We decided it makes sense to take it down. At that point, NetWalker was an incredibly widespread and popular ransomware. Folks were shelling out millions of dollars and we thought an enforcement action would make sense.”

They coordinated with law enforcement in Canada and Bulgaria to not only arrest Vachon-Desjardins but take over the group’s servers on January 27, 2021.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrested Vachon-Desjardins at his home in Quebec and found about half a million dollars in Canadian and U.S. currency in addition to about 719 Bitcoin.

Vachon-Desjardins is now facing charges of conspiracy to commit wire fraud, conspiracy to commit computer fraud, and several other charges based on his conduct with victims located in the Tampa, Florida area, according to Gammons.

When asked by The Record whether any other NetWalker members were identified, charged or arrested, Gammons pointedly said, “The only public charge right now is Sebastian Vachon-Desjardins.”

Jonathan Greig

is a Breaking News Reporter at Recorded Future News. Jonathan has worked across the globe as a journalist since 2014. Before moving back to New York City, he worked for news outlets in South Africa, Jordan and Cambodia. He previously covered cybersecurity at ZDNet and TechRepublic.