Senator proposes new encryption provision in bill against online child exploitation

Sen. Dick Durbin has been circulating an updated version of legislation designed to crack down on child exploitation materials online, with new wording that would do less to erode legal protections for encrypted communications, privacy advocates say.

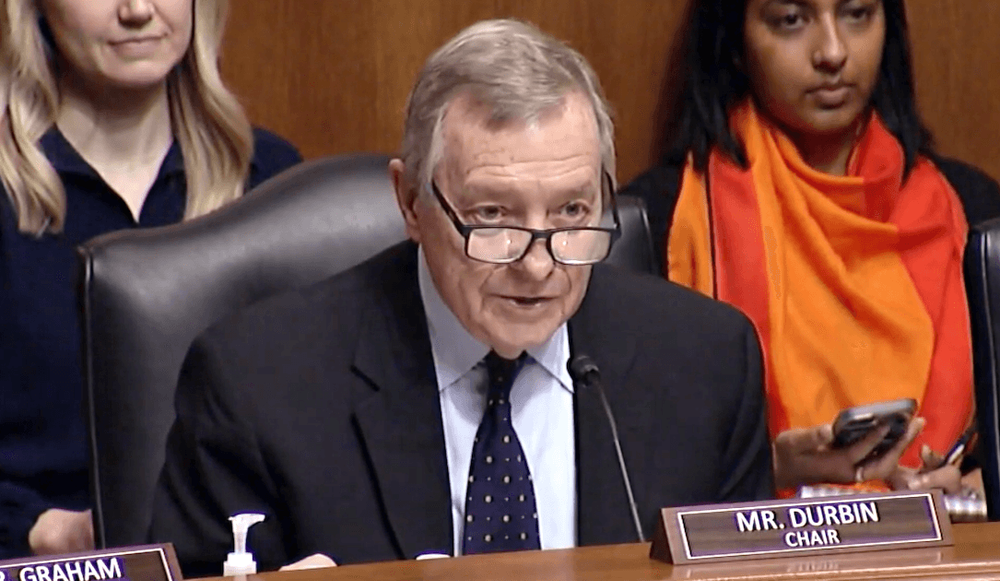

The new draft of the bill, as seen by Recorded Future News, comes as the Senate Judiciary Committee plans to hold a hearing Wednesday on technology and child exploitation, with CEOs from Meta, TikTok, Snap, Discord and X in attendance. Meta rolled out encryption on its Messenger app in December.

Three of the CEOs were subpoenaed to appear, and the hearing is expected to be tense and even hostile.

Durbin (D-IL), the Judiciary panel's chairman, introduced the bill — the Strengthening Transparency and Obligations to Protect Children Suffering from Abuse and Mistreatment Act (STOP CSAM) — in April. Another bill, the EARN IT Act, also contains language targeting encryption but is seen as having much less momentum.

The Judiciary Committee approved the STOP CSAM legislation in May with a provision saying that tech companies would be liable for "the intentional, knowing, or reckless hosting or storing of child pornography or making child pornography available to any person.”

The new draft would remove the word “reckless,” meaning that companies would have more legal protections when offering encryption on users’ personal communications. Privacy advocates have differing opinions on how significant the proposed changes to STOP CSAM are, but most agree the removal of “reckless” is an improvement.

“Removing liability for reckless acts could be a game changer for the STOP CSAM Act,” said Megan Iorio, senior counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. The new bill text doesn’t “broadly threaten encryption like previous versions and instead seems to be more focused on incentivizing companies to act on reported CSAM without breaking encryption, like by suspending accounts that have reportedly uploaded CSAM,” Iorio added.

Privacy advocates and proponents for encryption said the STOP CSAM bill has been gaining momentum in recent months, given Durbin’s status in the Senate Democratic leadership.

Law enforcement agencies have long sought to weaken how tech companies offer encryption in products like instant messaging, with the intention of keeping criminals from “going dark” online. Privacy advocates, however, generally want consumers to be able to protect their data as much as possible.

The Cooper Davis Act, a bipartisan bill proposing that social media companies and encrypted communications providers report illegal drug activity, was heavily shaped by the Drug Enforcement Administration, and included language saying platforms could be held liable if they “deliberately blind” themselves to discussions of drug law violations. That bill is now languishing in the Senate.

The proposed adjustment to STOP CSAM’s text is a signal that Durbin is doing all he can to push the legislation through, said Jenna Leventoff, senior policy counsel at the ACLU.

“I think that STOP CSAM has more legs because they are trying to make it less bad and might get some more support because of that,” Leventoff said.

Joining STOP CSAM and EARN IT in the Senate is another bill, the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), which appears to be the most likely to pass the full Senate and does not contain language that is seen as risky to encryption. EARN IT is written in a way that could cause companies to stop offering encrypted services, privacy advocates say.

Even with the “reckless” language removed from STOP CSAM, Leventoff said she still worries that the bill could be harmful.

“A platform by nature cannot know what content is being transmitted through encrypted services,” Leventoff said. “If you’re a platform and you're potentially subject to one of these rules [you may ask] ‘Am I going to be held liable for content that I don't know about?’ it might be, ‘I can't offer encryption.’”

Leventoff noted law enforcement’s hostility to encrypted services and said it is possible that if the legislation passes there could be an interpretation of “knowing” that leads to a “clamp down on encrypted services, because the services can't know” about exploitative content appearing on encrypted channels.

Last April, the FBI published a notice in the Federal Register about a proposal to “collect data on the volume of law enforcement investigations that are negatively impacted by device and software encryption.”

The agency’s website says that warrant-proof encryption prohibits it from amassing electronic evidence needed to prosecute cases even with a warrant or court order.

“End-to-end encryption and other forms of warrant-proof encryption create, in effect, lawless spaces that criminals, terrorists, and other bad actors can exploit,” the website says.

Leventoff also worries that legislators could meld the three bills together, leaving the strong anti-encryption language in EARN IT in play. However, even if a bill is passed with just a “knowledge” standard, she said, there is still a risk of many platforms walking away from providing the service.

“There's a calculus there — how much money do we earn from encryption and how much good will does this get us from our customer base?” Leventoff said.

Leventoff said she expects Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg to be asked about encryption, since its Messenger platform’s encryption feature debuted so recently. She said she will be watching the hearing closely to gauge how strongly Zuckerberg defends the service.

Andrew Crocker, surveillance litigation director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, seconded Leventoff’s concerns, saying he worries that both the EARN IT Act and STOP CSAM “would necessarily erode protections for encryption, pressuring providers to scan encrypted content (resulting in backdoors that endanger the privacy of all users) or creating the possibility of serious criminal and civil liability for offering encrypted services.”

Crocker said that he is especially concerned because the sponsors of the bills “have explicitly stated that one of their goals is to use the law to further the adoption of technology for scanning the content of encrypted messages.”

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering digital privacy, surveillance technologies and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.