‘Denim Tsunami’ and ‘Mulberry Typhoon’: Microsoft alters the way it names hacking groups

Cybersecurity specialists may find it hard to remember all the different names companies use to refer to threat actors — some use a number system, while others use colors, animals and adjectives like “fancy” and “charming.”

Now they have one more naming scheme to remember: On Tuesday, Microsoft announced that it’s switching from a taxonomy based on chemical elements to one that uses weather-themed names to classify hacking groups.

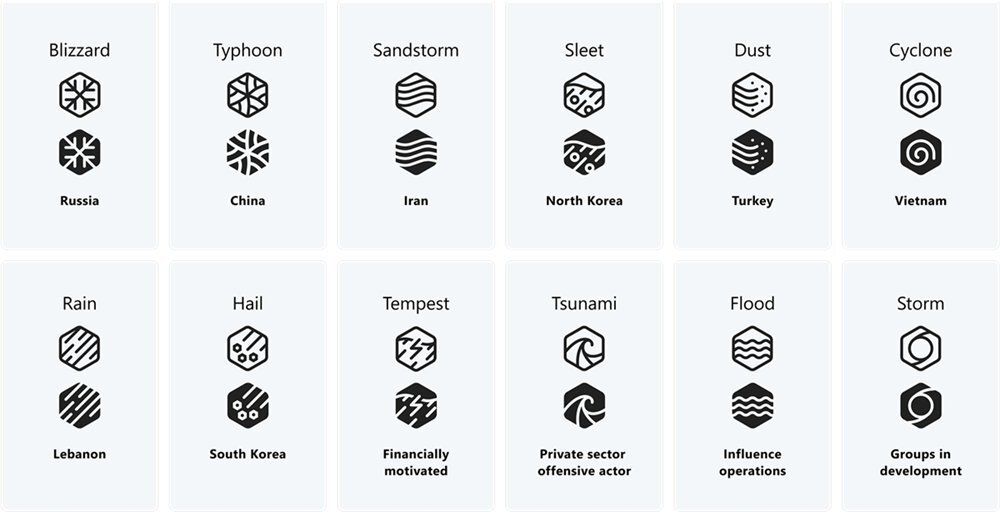

In a blog post, the tech giant outlined how its new naming scheme will work, explaining that countries will be assigned certain weather conditions – like blizzard for Russia, sleet for North Korea, Typhoon for China and Sandstorm for Iran – while specific groups within nations will be classified with an adjective like a color.

As an example, Microsoft said that in its most recent report about a nation-state group from Iran, they will rename the group involved as “Mint Sandstorm” after previously calling them Phosphorus.

“The complexity, scale, and volume of threats is increasing, driving the need to reimagine not only how Microsoft talks about threats but also how we enable customers to understand those threats quickly and with clarity,” Microsoft’s John Lambert said.

“With the new taxonomy, we intend to bring better context to customers and security researchers that are already confronted with an overwhelming amount of threat intelligence data.”

Lambert explained that the new system will allow them to better organize the threat groups they track and provide simpler ways of classifying actors. Researchers and security teams will “instantly have an idea of the type of threat actor they are up against, just by reading the name.”

He added that Microsoft currently tracks more than 300 unique threat actors including 160 nation state groups, 50 ransomware gangs and hundreds of other types of attackers. Microsoft has reclassified all of the actors it tracks using its new naming taxonomy.

Microsoft acknowledged that several other security giants use different naming taxonomies and plan to include those in their reports.

In addition to specific weather event “family” names for actors from specific governments, Microsoft will use "tempest" for financially motivated actors, "tsunami" for private sector actors and "flood" for influence operations.

The term "storm" will be used for groups in development – previously tagged with the letters DEV – alongside a four-digit number. This will be used until more information is learned about the actor.

“To meet the requirements of a full name, we aim to gain knowledge of the actor’s infrastructure, tooling, victimology, and motivation. We expand and update the definitions supporting our actor names based on our own telemetry, industry reporting, and a combination thereof,” Lambert explained.

The new names will be accompanied by a symbol that Microsoft believes will make it simpler to identify for defenders. The entire process of switching over to the new system will be completed by September, Lambert said.

A reference guide was created to help with the transition.

Naming confusion

Cybersecurity experts were mixed on the move, with some telling Recorded Future News that the move would only confuse defenders while others said it was a good idea.

Phil Neray, chief marketing officer at cybersecurity firm CardinalOps, said Microsoft’s previous naming system made it difficult to search for information about specific threat actors. He used the example of Nobelium – Microsoft’s term for APT29 or Cozy Bear from Russia – noting that multiple articles online focused on the radioactive metal and not the hacking group.

“Microsoft is an important driving force behind both identifying threat actor groups and working with law enforcement and government agencies worldwide to disrupt their activities,” he said. “I'm not sure the new naming scheme will address this issue, but in any case, most organizations currently use the MITRE ATT&CK framework — which has its own naming scheme — as the de facto standard for sharing information about adversary groups and their playbooks.”

Mike Parkin, a technical marketing engineer at Vulcan Cyber, said that on the surface the switch is a good idea, but he questioned whether the trend would catch on outside of Microsoft’s ecosystem.

In general, he explained, defenders have to deal with a confusing array of names used for government hacking groups because every major security company uses different names.

Parkin also questioned how Microsoft’s approach would work with groups that straddle the line between being financially-motivated and government-backed.

“Which takes priority? Is a ransomware group in Iran named as a nation-state actor, or as a financially-motivated threat? And will they be including information on how other organizations track it?” he asked. “A common naming convention is not a bad idea at all. But it doesn't solve the ‘they call it something else’ issue.”

Roger Grimes, a cybersecurity expert at KnowBe4, added that he was generally not a fan of vendor-created threat names because it makes it harder to know if the same groups are being discussed.

It would be far wiser, he said, for every vendor in the world to agree on a single threat name taxonomy and apply those to every discussion of the same threat group.

The hodgepodge of naming taxonomies make it harder for defenders, Grimes explained, adding that it’s difficult to get competitors to agree on a single taxonomy.

“Still, this is one of those times that I wish we had a kumbaya moment. We are decades past when it made sense to have globally agreed upon threat names,” he said. “Why can't the good side get its act together? Why make it knowingly harder?"

Jonathan Greig

is a Breaking News Reporter at Recorded Future News. Jonathan has worked across the globe as a journalist since 2014. Before moving back to New York City, he worked for news outlets in South Africa, Jordan and Cambodia. He previously covered cybersecurity at ZDNet and TechRepublic.