How the Pentagon learned to love vulnerability disclosure

Inside the national cyber strategy released last month by the Biden administration was a call for “coordinated vulnerability disclosure” across “all technology types and sectors” to help collect and share information about flaws in software, hardware and systems nationwide.

The appeal marked the latest step in the evolution of a practice that gained early acceptance in Washington in perhaps the most unlikely of places: the Department of Defense. About seven years ago, the famously bureaucratic and secretive DoD embraced the idea that people outside the department should be encouraged to spot bugs in its vast ecosystem of publicly accessible information networks and systems.

Since then, the global cybersecurity researcher community has responded enthusiastically. Last week, the department’s Cyber Crime Center (DC3) announced its vulnerability disclosure program had processed 45,000 reports, and that figure promises to grow as researchers are encouraged to keep ferreting out weaknesses.

“We can’t do it alone. I mean, you can’t boil the ocean,” Melissa Vice, the center’s VDP director, told The Record late last week.

The vulnerability effort sprang from the success of the department’s first-ever bug bounty program, called Hack the Pentagon, in 2016 — part of a broader push by then-Defense Secretary Ash Carter to bring commercial software best practices into the government’s largest bureaucracy. The initial contest, which benefited from Carter’s full-throated support, unearthed nearly 140 unique security vulnerabilities on some of the department’s public websites over a 24-day period and issued about $100,000 in payouts.

However, the event — which has gone on to inspire numerous bounty iterations across the armed services and civilian agencies, including the Homeland Security Department — also raised fresh questions about who would ensure the flaws were fixed or address any new ones that arose, such as through a previously unknown zero-day exploit.

“We didn't really have a mechanism to be able to do that,” according to Chris Lynch, the founding director of the Pentagon’s then Defense Digital Service, which ran the event in conjunction with bug bounty platform HackerOne. “So having this idea and implementing something of a ‘see something, say something’ system is what the VDP became.”

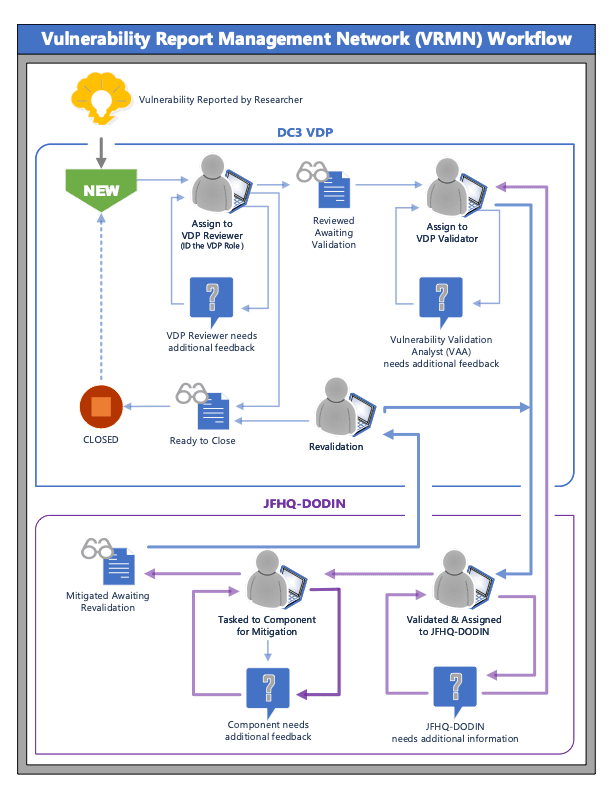

Currently, once a proof-of-concept is submitted and checked against metrics, including the NIST National Vulnerability Database, it’s up to the Joint Force Headquarters DoD Information Network to issue the tasking order for the system owner to remediate.

Attracting the hackers

Classified systems, to this day, remain off-limits. But the Pentagon’s “attack surface” for ethical hackers has continued to expand.

The disclosure program received a massive upgrade in 2021 when Pentagon leaders expanded its scope. In addition to public-facing websites and applications, white-hat hackers were given the go-ahead to scour all publicly accessible DoD information systems, including databases, networks, internet of things (IoT) devices and industrial control systems.

“Basically we went from 2,400 units to about 24 million units overnight,” said Vice, who first joined the cybercrime center three years ago as its chief operations officer.

“And then COVID came along,” she added. “You take all of those Cheeto dust-fingered, Monster Energy-drinking hackers of the world and you lock them in their domicile. Guess what they're going to do?”

Submissions skyrocketed. The Maryland-based center went from processing an average of 300 vulnerability reports each month up to 900 or even 1,200 in fiscal 2020 and 2,000 per month in fiscal 2021, according to Vice. The number has since fallen back to its pre-pandemic level.

In its annual report earlier this month, the DC3 said that since the program's launch, 25,762 of the defects reported had been deemed “actionable” and required some kind of remediation.

The white-hat mindset

Today, the VDP serves as a bridge between the buttoned-up DoD and the global community of ethical hackers.

Unlike a bug bounty event, the program doesn’t pay out cash rewards. Instead, DC3 aims to give researchers credibility by recognizing and promoting their discoveries, via tweet or by bestowing the honorific of report of the month or report of the year when graded against the Common Vulnerability Scoring System. In a first, last year’s award went to an American, who received a swag bag, including a sweatshirt with the program’s logo and other tchotchkes from the Pentagon. (The first year’s winner lived in Ukraine, while other previous champs hailed from Kosovo and Rome.)

The August 2022 hacker of the month, Sudhanshu Rajbhar, said he prefers the cash rewards of the bug bounty events, but he also appreciates the ability to safely report bugs through the VDP. He said that some hackers who once drew attention for defacing DOD websites now submit bugs to the official program.

“Their team is mature and very professional, understands the impact of the reported bugs. Overall it has been a great experience working with them,” said Rajbhar, a university student in India who uses the Twitter handle @sudhanshur705.

“You don't need any degree or any qualification for this, all you need is a hacker mindset and a never ending thirst for knowledge,” Rajbhar said.

An eye on expansion

Vice said the center is looking to boost the program’s “scalability” through new partnerships in the research community and academia, as well as potentially expanding on two recent pilot programs that proved successful.

The first was a yearlong, voluntary effort that scrubbed a sliver of the public networks belonging to the 300,000-plus contractors in the defense industrial base — a favorite target of foreign hackers looking to pilfer national security secrets and intellectual property — and turned up more than 400 flaws.

“I think there's real strong indicators that we will see a resurgence of this type of program coming forward or pilot 2.0,” according to Vice.

The second was an event by HackerOne under the auspices of the VDP that saw hackers dig into DoD networks for cash.

“VDPs are a timed process, you only get credit for the very first one to initiate it and submit it into the actual, so you can't sit on these,” Vice explained. Traditional bug bounty programs, by contrast, are “very targeted and they're by invitation only. It's a very different crowd set that you're speaking to, in a VDP versus a bug bounty, but we can see the goodness of having those two conjoined.”

Meanwhile, the center continues to field calls from other agencies (the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency in 2020 ordered civilian entities to create them), states and foreign governments asking for tips on how to set up their own programs and weed out flaws in the networks.

Lynch, now the co-founder and chief executive officer at software contractor Rebellion Defense, marveled over the program’s longevity and impact through Washington and beyond.

“It’s amazing,” he said. “To see the VDP take off, get continued funding and support and be successful, it's just a reminder that at the end of the day, this notion of you know, security through obscurity — and keeping our head in the sand around our vulnerabilities and weaknesses — it's just not the right approach.”

Martin Matishak

is the senior cybersecurity reporter for The Record. Prior to joining Recorded Future News in 2021, he spent more than five years at Politico, where he covered digital and national security developments across Capitol Hill, the Pentagon and the U.S. intelligence community. He previously was a reporter at The Hill, National Journal Group and Inside Washington Publishers.