CrowdStrike tells Congress of two process changes to address July outage incident

CrowdStrike is making two changes to how it pushes out updates for its security tools after a July incident left thousands of airports, businesses and governments scrambling to recover from outages.

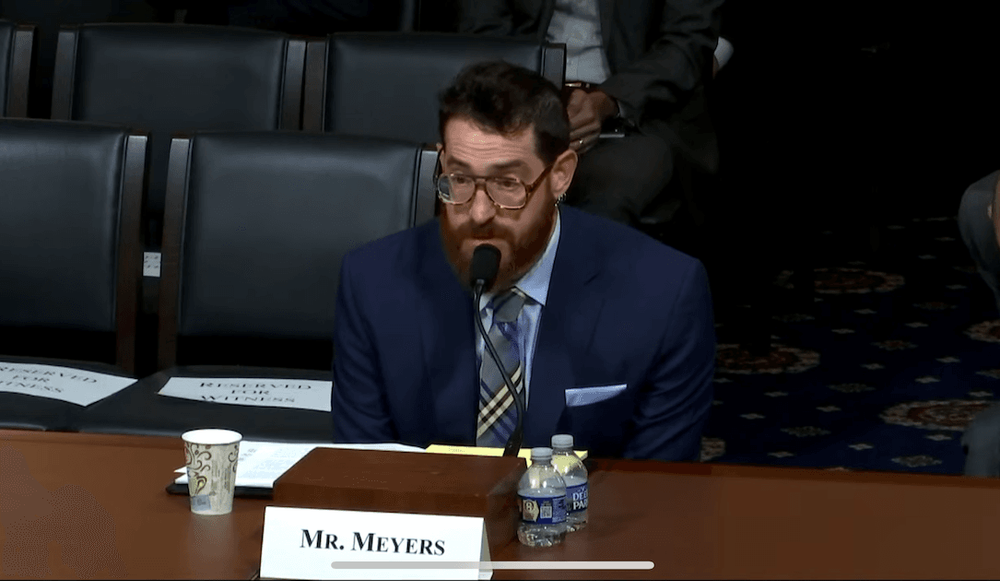

Adam Meyers, senior vice president at the cybersecurity company, told a House subcommittee on Tuesday that customers will now be able to choose whether they are among the first to receive content updates — essentially serving as guinea pigs for new changes — or schedule to get the updates at a later date.

Meyers also explained at length the internal changes CrowdStrike is making to how the company verifies the updates.

The company previously admitted that validators used for dozens of updates over the last decade failed to catch the faulty update that disabled more than 8.5 million Windows devices around the world.

Devices that are integral to thousands of critical systems across the world – including airlines, hospitals and banks – were running CrowdStrike’s Falcon endpoint sensor for protection.

“The configuration update that occurred, the content update, was not code. This was threat information that was being provided to the sensor,” he said, noting that there are times when CrowdStrike sends out 10-12 updates a day.

“The content updates had not previously been treated as code because they were strictly configuration information,” he told the Homeland Security Subcommittee on Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection.

“What we have undertaken since the July 19 incident is that we are now treating the content updates as code, which is something that I don't believe to be an industry standard at this time.”

The difference, according to Meyers, is that code at CrowdStrike goes through a more stringent checking process that it calls “dogfooding.” Code goes through extensive quality assurance and checks before being deployed internally. After more testing it is sent out to early adopters and then finally to more general customers.

Meyers said he was hopeful this would prevent any future incidents where faulty updates could be sent out widely. He was not asked why the updates were not previously treated as code or what specifically would be different about how the updates are checked. CrowdStrike did not respond to emailed questions about this as well.

Kernel debate

Meyers also responded to one of the biggest complaints raised since the incident — CrowdStrike’s deep access to the Windows systems where its software is installed.

Several members of Congress pressed Meyers about why CrowdStrike needs this kernel-level access to devices.

Meyers called kernels the “central most part of an operating system” and said it is responsible for interfacing with all the hardware associated with that operating system or that computer. He noted that CrowdStrike is one of the many vendors that uses the Windows kernel architecture.

He echoed a blog CrowdStrike released last month, arguing that due to Windows’ current design, security products providing endpoint protection services need kernel access to “provide the highest level of visibility, enforcement and tamper-resistance.”

Meyers added that cybercriminals and nation state actors want to gain kernel access themselves, necessitating security products to defend devices at that level.

“Kernel visibility is certainly critical to ensuring that a threat actor does not insert themselves into the kernel themselves and disable or remove the security products and features,” he said.

Microsoft has also addressed this issue at recent events and in a blog about the incident. Executives at other security companies told Microsoft that it “remains imperative that kernel access remains an option for use by cybersecurity products to allow continued innovation and the ability to detect and block future cyberthreats.”

Meyers dodged several other questions about whether they believe the incident should be investigated by the Department of Homeland Security’s Cyber Safety Review Board or what their plan is for compensating the thousands of businesses that were damaged financially by the outages.

CrowdStrike — which has more than 20,000 customers including several U.S. government agencies and more — has already responded forcefully to threats of litigation from companies like Delta Airlines, which says it lost more than $500 million after it was forced to cancel thousands of flights due to CrowdStrike’s update.

Economists estimate the outage caused by CrowdStrike’s update will cost Fortune 500 companies more than $5.4 billion.

The company is also facing backlash from its own investors, including the Plymouth County Retirement Association, which filed a lawsuit in Texas after CrowdStrike’s share price plummeted due to the incident.

Jonathan Greig

is a Breaking News Reporter at Recorded Future News. Jonathan has worked across the globe as a journalist since 2014. Before moving back to New York City, he worked for news outlets in South Africa, Jordan and Cambodia. He previously covered cybersecurity at ZDNet and TechRepublic.