Inside Conti leaks: The Panama Papers of ransomware

The ransomware group Conti has only been around for two years, but in that short time it has emerged as one of the most successful online extortion groups of all time. Last year alone, it generated an eye-popping $180 million in revenue, according to the latest Crypto Crime Report published by virtual currency tracking firm Chainalysis.

The group almost exclusively targets companies with more than $100 million in annual revenues, which, in turn, allows it to routinely extract multimillion-dollar ransom payments from its victims.

The group seemed poised to continue in that vein until late last month, when it made a fatal mistake: it publicly supported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The group’s allegiance clearly rubbed someone the wrong way. Within days, the gang’s internal Jabber/XMPP server – which carried their private messaging channel – was hacked, and two years of the group’s chat logs appeared on a new Twitter handle called @ContiLeaks.

“Greetings,” one tweet began. “Here is a friendly heads-up that the Conti gang has lost its s****” The message included a link that would allow anyone to download almost two years of private chats. “We promise it is very interesting,” the tweet added.

‘Panama Papers’ of Ransomware

John Fokker, who runs the investigations team at Trellix, a cybersecurity company, has been combing through the chats since they were released. “We see nicknames that we've seen before in other ransomware groups,” he said. “We see infrastructure that belongs to [the famous banking Trojan] Trickbot. We see passwords. I call this the Panama Papers of ransomware. ”

The Panama Papers rocked the banking world by laying bare how a law firm that specializes in helping the super rich stash their money in offshore accounts makes all that happen. The Conti leaks are the ransomware corollary because the chat logs illuminate everything from mundane details of how Conti is organized to new anecdotes about the group’s possible links to the Kremlin.

The group fluctuated in size from 65 to more than 100 salaried employees. They spent thousands of dollars each month to buy security and antivirus tools to see if they could detect their malware, and then deployed them on their own systems for protection.

Last August, the chat logs show, a manager named “Reshaev” wrote to someone named “Pin” and asked him to check on the Conti network once a week to ensure everyone was being careful about security. He tells Pin to install endpoint detection and response, a security technology that continually monitors an "endpoint" to mitigate malicious cyber threats, on every administrator’s computer. He asks him to set up a more complex storage system too.

“There’s a big case study to be done here for years,” Fokker said.

‘Big game hunting’

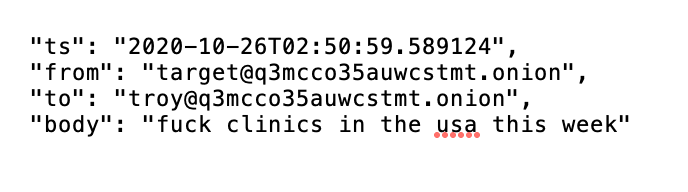

Back in the Fall of 2020, two Conti hackers started a message thread. They had their fingers on keyboards that would soon set a wave of ransomware attacks against some 400 hospitals in the U.S. and Britain. This was when the COVID-19 pandemic was in full swing, and locking up hospital computers was especially cruel. “F— the clinics in the USA this week,” one of the hackers, who went by the handle ‘Target’ wrote, adding that the attack would certainly set off a panic.

Conti specializes in ‘big game hunting,’ which, in the hacking world, involves digging into the networks of high-value targets – like huge hospital systems – to find vulnerabilities, extracting important information, and then installing malware on their systems to prevent anyone from accessing their data until they pay a ransom.

The group even had a bit of an incentive operation, to focus the minds’ of their victims on just what was at stake. Before installing the malware Conti hackers would extract important, sometimes proprietary information, and then in their ransomware note explain how much data they stole, and what it might mean to the company if the information was sold or made public.

“Hi There! This is the Conti Team,” read one of their ransomware messages captured in a report on the group from Prodaft, a cybersecurity company in Switzerland. “As you already know we have infiltrated your networks… we have downloaded your critical information with a total volume of 450 GB.”

It then goes on to lay out what might happen to the company if that information was made public. Then they offered a helpful link to a kind of victim shaming blog they had built especially for that purpose. In addition to hospital systems, Conti (and its predecessor group Ryuk) targeted big companies like Garmin, Pitney Bowes, and Tribune Publishing.

‘Just like us’

Émilio Gonzalez works on a blue team for a large Canadian company. That means he defends its computer network from actors like Conti. He stumbled on the chat logs on Twitter.

“And I thought it was really cool and I wanted to get my eye and my hands on it,” he said from his home office, swinging back and forth in one of those big ergonomic chairs that gamers have. His fingernails are painted black. He’s been reading the chat logs for three days so far. “I have a day job, so I only do it during lunch and the evenings, but I've spent a lot of hours on that and I'm not even close to done having seen everything.”

What has surprised him is how much he identifies with the Conti hackers whose messages he’s reading. “They are just like us,” he says. They ask for paid leave, share office gossip, and make plans with co-workers. “It makes sense. It's the same for them. They want to connect with people and they want to live their life, even if they’re what we consider bad guys.”

Consider the case of a Conti manager named Target. It turns out he’s a bit of a jerk boss; the kind of guy who shows he’s impatient by sending one word emails in succession like: where… are… you? The Saturday before those hospital attacks, he put out an all call and it was not a request for help, it was a demand. “Everyone is working today,” he declared. No explanation, no apologies.

The chats show a clear hierarchy. You have middle managers, like “Target;” worker bee programmers who write the malicious code that makes ransomware work; an IT team that maintains their servers, backs up their data, and can quickly break it all down.

Which begs the question: how could such a sophisticated hacking group fail to encrypt their chats?

Discordian, who is a kind of spokesperson for the hacktivist collective Anonymous, said Conti’s lack of operational security is jaw dropping.

“The dumb part of this is the way they did it in an unencrypted matter,” he said. “That's unthinkable, right? They must be shaking in their boots right now, because a lot of their identities will be revealed through these leaks, a lot of the way they do their operations.

Get out of jail free card?

Trellix’s John Fokker has been tracking Conti – and its predecessor Ryuk – for years. He used to be part of the Dutch National High-Tech Crimes Team and he followed all the big ransomware groups like Conti. So he’s been particularly intrigued by the contents of these chat logs.

“We could see very interesting conversations, nicknames that we've seen before in other ransomware groups, passwords,” he said, adding that it is helping them connect lots of dots and in particular two of these dots involve Conti and Russian law enforcement.

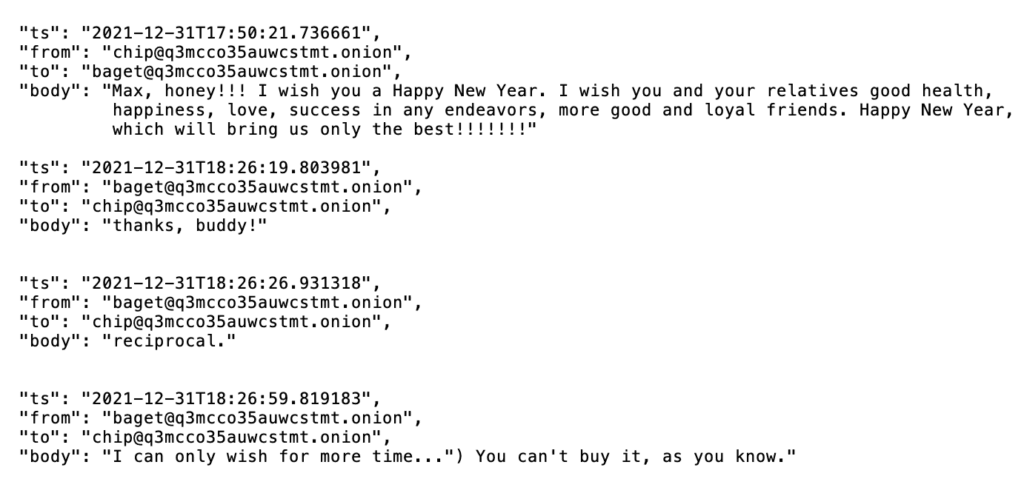

In particular, he points to an exchange between two members of Conti in which they are talking about Bellingcat, a Netherlands-based investigative journalism group. They focus on fact-checking and open source intelligence.

In their conversation the hackers seem to be searching the Bellingcat network on behalf of someone else. “And what really stood out was the conversation that took place that they said like, ‘Okay, this is very interesting information. We need to save this.’ And they literally said, ‘Okay, look for stuff that's related to Navalny.’”

Alexei Navalny is a jailed Russian opposition leader who is Vladimir Putin’s nemesis. In 2020, after surviving an assassination attempt, Navalny worked with Bellingcat to identify his would-be killers and eventually got one of the assassins to confess to the attempt over the phone. So that could explain why they were looking around the Bellingcat network.

“They literally said, ‘Okay, save this stuff related to Navalny and save it in the folder Navalny FSB,” Fokker explained, referring to Russia’s Federal Security Service, which conducts counter intelligence and internal security.

Here is the chat between two conti hackers (h/t @HarioMenkel) pic.twitter.com/xwfpShAnbr

— Christo Grozev (@christogrozev) February 28, 2022

“So this basically confirms a lot of what we have always been suspecting,” Fokker said. “Obviously we don't know if they were actually guided by a state, but it could indicate there might've been a relationship. It could have been their get out of jail free card.”

Fokker says it could help explain why the group came out supporting Russia after the invasion. “Sometimes the truth is more amazing than what we could think of, but for now this is the running hypothesis that there is some level of interaction that has taken place.”

What’s so extraordinary about the leaks is that the messages allow the world to examine the group at close range and in real time, with all its eccentricities and personalities.

In the past, analysts learned about these groups in snippets, like when someone got arrested. This is different because it provides a glimpse of Conti when the hackers’ guards are down, which could be a boon for law enforcement.

“Maybe it is the end of Conti in the fashion that we knew,” Fokker said, adding they haven’t been outed or doxxed or identified or arrested yet. “As long as these people are still not arrested, they can still commit the same crime, the skill doesn't fade in that regard. And they can still regroup somewhere else.”

Which brings us to the unintended consequences of the leak: the way Conti is likely to react in the wake of all this. Fokker expects the group will borrow from al-Qaeda and the terrorism model and instead of organizing like cohesive army, they could turn to more independent cells, which are harder to track.

“I wouldn't be surprised,” Fokker said. “Long story short this whole eco climate of ransomware is going to become more fluid and there will be more self-sustained groups that will work less as a hierarchy and more as a network. I would not be surprised if you see something like that.”

Sean Powers and Will Jarvis contributed to this report.

Dina Temple-Raston

is the Host and Managing Editor of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”