As cars hoover up more and more driver data, is it time to regulate the industry?

Cars are “connected computers on wheels” and should be treated as such. That's according to the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA), which recently announced its enforcement division will review the data privacy practices of connected vehicle manufacturers.

It’s about time, according to privacy experts — and even some auto industry insiders.

Automotive manufacturers, and in some cases insurers, are increasingly harvesting data from car owners, often without consumers being aware of the practice, according to car hacker and privacy expert Marc Rogers, who recently co-founded the artificial intelligence anomaly detection and data analysis company nbhd.ai and is known for having hacked a Tesla with an iPhone at the DEF CON hacking conference.

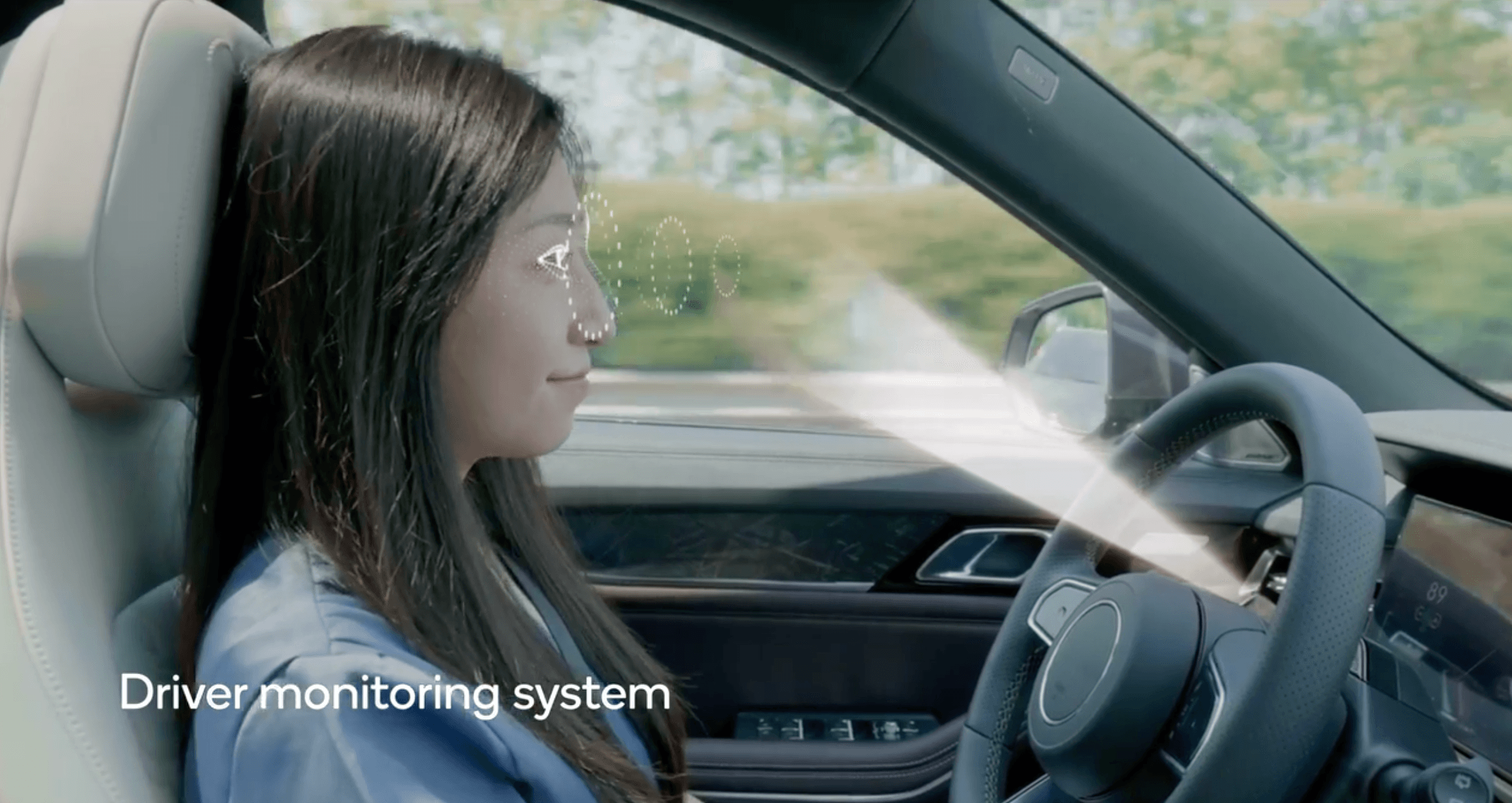

Calling connected cars complex computers, whose infotainment systems in many ways function like mobile phones, Rogers said Tesla and many other auto manufacturers exponentially increase the number of sensors they place in their cars every year.

Citing Tesla, Rogers said cameras and wireless telemetry record drivers’ actions and stream data back to headquarters, in part for safety reasons. But Tesla’s data harvesting practices are far from unique and have increasingly become industry standard, Rogers said.

“How you drive is being recorded, where you drive is being recorded,” Rogers said of connected cars, which easily cull data from apps, sensors, and cameras embedded in infotainment systems and other smart devices built into the vehicle. “The industry is moving faster than the privacy regulators are.”

Connected cars are often “left out of conversations” about privacy even as they collect ever more data, according to Adonne Washington, policy counsel for data, mobility, and location at the Future of Privacy Forum, a nonprofit focused on data protection and privacy.

Washington said that carmakers must ensure they have “strong and clear processes for responding to consumer rights” and allow them to object when their data is leveraged for advertising, now a common practice in the industry.

The California legislature is also taking the issue on. A Senate bill that would require auto manufacturers to alert drivers when they collect images from in-vehicle cameras and outlaw their sale to third parties or for advertising purposes recently advanced out of committee.

In its announcement on Monday, CPPA noted that connected vehicles — a large portion of newer model cars — contain location sharing, web-based entertainment, smartphone integration, and cameras.

The agency’s enforcement staff is “making inquiries into the connected vehicle space to understand how these companies are complying with California law when they collect and use consumers’ data,” Ashkan Soltani, CPPA’s executive director, said in a statement.

A safety issue?

The consulting firm McKinsey in 2014 estimated that connected cars generate up to 25 gigabytes of data an hour. The Automotive Edge Computing Consortium has updated that number, reporting that industry estimates show the connected vehicle “ecosystem” will need to transfer up to 10 billion gigabytes of data to the cloud each month, which it said is “vastly more than networks can handle today.”

Many auto manufacturers bury their data collection practices in their licensing agreements, but most don’t disclose that the data they reap is often being shared with third parties like data brokers, Rogers said.

A screenshot from an advertisement for Qualcomm's Snapdragon Cockpit Platform.

A screenshot from an advertisement for Qualcomm's Snapdragon Cockpit Platform.

A renowned white hat hacker, Rogers is a senior technical adviser at the Institute for Security and Technology, head of security for DEF CON, and co-founder of CTI-League, which formed as a collaboration of more than 1,500 global cybersecurity experts, incident responders, law enforcement, and government agencies defending critical infrastructure across 76 countries.

Rogers stopped short of calling on automakers to no longer collect data since he said the practice is partially done for safety reasons. But manufacturers should be forced to limit what data is collected and how it is used while allowing consumers the opportunity to opt out, he said.

Those closer to industry focus more on increasing transparency than on limiting data collection overall. Data collection, and the selling of data, is an important part of the future automotive industry business model, according to Jennifer Tisdale, CEO of the cybersecurity company GRIMM, which is strongly connected to the automotive industry and has a Michigan-based cybersecurity research lab focused in large part on connected vehicles.

Tisdale previously served as an automotive cybersecurity adviser to the state of Michigan and said she believes there needs to be a layered public awareness campaign to help consumers understand that much of the data being collected enhances vehicle safety. She said that because a lot of the technology being integrated is used for safety features there are multiple agencies that need to coordinate data privacy regulation.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the regulating body for auto industry safety practices, can only provide data privacy recommendations, as opposed to regulation, Tisdale said, so the agency is now coordinating with the Federal Trade Commission on how to manage data privacy rules for cars.

Neither agency responded to requests for comment.

“We are seeing a lot of federal action and coordination that we've not seen previously,” Tisdale said, adding that this more deliberate engagement between agencies is important because federal standards are critical.

“The more cohesion you can get across the United States in terms of at least baseline regulation for how to protect consumer data would be incredibly important,” she said. “And right now, I don't think we're really seeing that… I don't believe we can go too much longer without having something more.”

‘Keys to the 21st century kingdom’

The auto industry is playing catch up when it comes to understanding how it uses and protects data, said Faye Francy, the executive director of the Automotive ISAC, an industry-driven organization focused on automotive cybersecurity risks.

“Some other industries have looked at it a little bit deeper than we have because we're newer to this environment,” Francy said. “This is build it and it’s also trying to understand it simultaneously… It's a huge challenge.”

But she added that manufacturers, while implementing data practices individually and in different ways, know they must master the issue.

“Data is the keys to the 21st century kingdom,” she said.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, a trade association representing the automotive industry, did not respond to a request for comment.

Consumers need basic questions answered, particularly about the data brokers manufacturers may be selling to, Rogers said. Data brokers buy information from a variety of sources to profile consumers and then package and sell it, often to marketers and law enforcement.

Rogers said vehicle data is particularly valuable to marketers who want to understand which locations different segments of drivers, based on their cars, may frequent.

“Who are they? How are they monetizing the data? How do they intend to monetize the data in the future?,” he asked, referring to data brokers. “None of that I think is made obvious to anyone. And if you talk to the average person, and ask them what data their car is sharing, I don't think they would have a clue.”

Rogers said some cars now have microphones recording consumers’ voices and cameras collecting images of their faces while others use fingerprint-controlled ignitions.

“If you give out your biometrics once, like your face, you can't get it back,” he said.

Insurers are also leveraging data to profile customers, like Progressive’s Snapshot program, which Rogers said relies on a module that is plugged into a car’s OBD-II port, monitoring speed, mileage, and other data points.

With Snapshot, a voluntary program promoted as an opportunity for discounts, he said Progressive can see how hard consumers press the accelerator, where they go, and how fast they drive, among other data which allows the company to set insurance rates.

“That’s the future that we're hurtling towards,” Rogers said, adding that users of the Snapshot program might become uninsurable under the program. Progressive declined to comment.

“That data is increasingly becoming valuable, and it's being seen as an additional source of revenue.”

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering digital privacy, surveillance technologies and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.