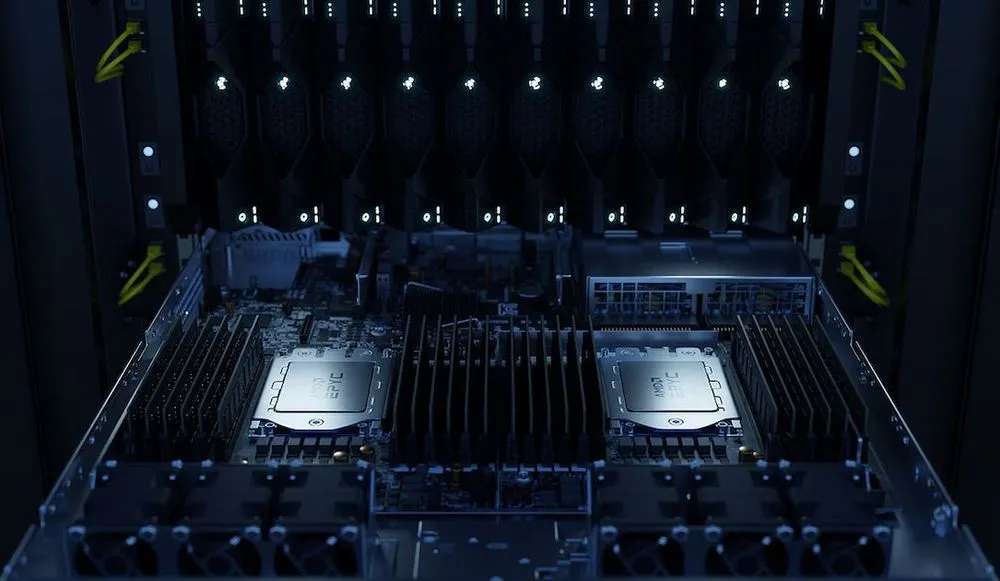

BadRAM: $10 security flaw in AMD could allow hackers to access cloud computing secrets

Researchers have unveiled a new way to bypass a key security protection used in AMD chips that could allow hackers with physical access to cloud computing environments to snoop on those services’ clients.

Named “badRAM” and described as the “$10 hack that erodes trust in the cloud” the vulnerability was announced on Tuesday and, similar to other branded vulnerabilities, is being disclosed on a website with its own logo. It will be detailed in a paper to be presented at the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2025 next May.

AMD has already issued firmware updates for the vulnerability, which affects computer processors used worldwide — including by cloud computing giants such as AWS, Google, Microsoft and IBM. As of publication, those companies did not respond to confirm whether they have applied the mitigations.

An AMD spokesperson said the company “believes exploiting the disclosed vulnerability requires an attacker either having physical access to the system, operating system kernel access on a system with unlocked memory modules, or installing a customized, malicious BIOS.

“AMD recommends utilizing memory modules that lock Serial Presence Detect (SPD), as well as following physical system security best practices. AMD has also released firmware updates to customers to mitigate the vulnerability.”

Wait, what’s the issue and what’s the impact?

AMD’s memory modules use something called Secure Encrypted Virtualisation (SEV) to protect data in cloud environments. SEV basically encrypts the memory used by virtual machines so that cloud customers don’t need to worry about their service provider being nosey.

But researchers have found they can bypass these protections “for less than $10 in off-the-shelf equipment,” by using that rudimentary hardware to “trick the processor into allowing access to encrypted memory.”

For an attacker to pull this off at one of the large cloud computing services, they would need physical access to the SPD chip on the memory module. This chip is “a little memory chip on the RAM module that basically stores the information about the module’s capacity,” as David Oswald, one of the researchers, from the University of Birmingham, explained to Recorded Future News.

By tampering with the contents of this chip, they can force the memory module to provide false information about its size, “tricking the CPU into addressing 'ghost' memory regions that don't exist,” as the researchers state.

“This leads to two CPU addresses mapping to the same DRAM location. And through these aliases, attackers can bypass CPU memory protections, exposing sensitive data or causing disruptions.”

“The whole assumption in memory is that you write to one place and it just goes to that place,” explained Oswald. “Technically, it’s called aliasing, because you suddenly have two ‘places’ that go to the same location … The whole AMD security technology is built on the assumption that there is no aliasing.”

The badRAM website warns there are several ways that this tampering could happen — from corrupt or hostile employees at cloud providers, through to law enforcement officers with physical access to the hardware.

It is also potentially possible to exploit the badRAM bug remotely too, although not in the case of AMD memory modules. For all manufacturers who fail to lock the SPD chip on their memory module, this would leave those modules “vulnerable to modification by operating-system software after boot,” and thus to remote hackers with control of the target device.

Oswald told Recorded Future News there was no evidence of this vulnerability being exploited in the wild. He added that the team found Intel’s chips already contained mitigations against badRAM attacks, while they could not test Arm’s modules as they were not commercially available.

The research was carried out by a consortium of experts from KU Leuven, Belgium; the University of Luebeck, Germany; and the University of Birmingham, U.K.

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative, now Virtual Routes. He can be reached securely using Signal on: AlexanderMartin.79