A mysterious threat actor is running hundreds of malicious Tor relays

Since at least 2017, a mysterious threat actor has run thousands of malicious servers in entry, middle, and exit positions of the Tor network in what a security researcher has described as an attempt to deanonymize Tor users.

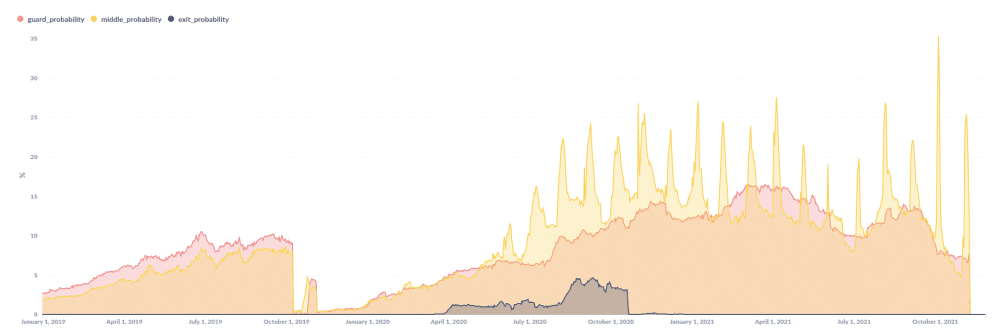

Tracked as KAX17, the threat actor ran at its peak more than 900 malicious servers part of the Tor network, which typically tends to hover around a daily total of up to 9,000-10,000.

Some of these servers work as entry points (guards), others as middle relays, and others as exit points from the Tor network.

Their role is to encrypt and anonymize user traffic as it enters and leaves the Tor network, creating a giant mesh of proxy servers that bounce connections between each other and provide the much-needed privacy that Tor users come for.

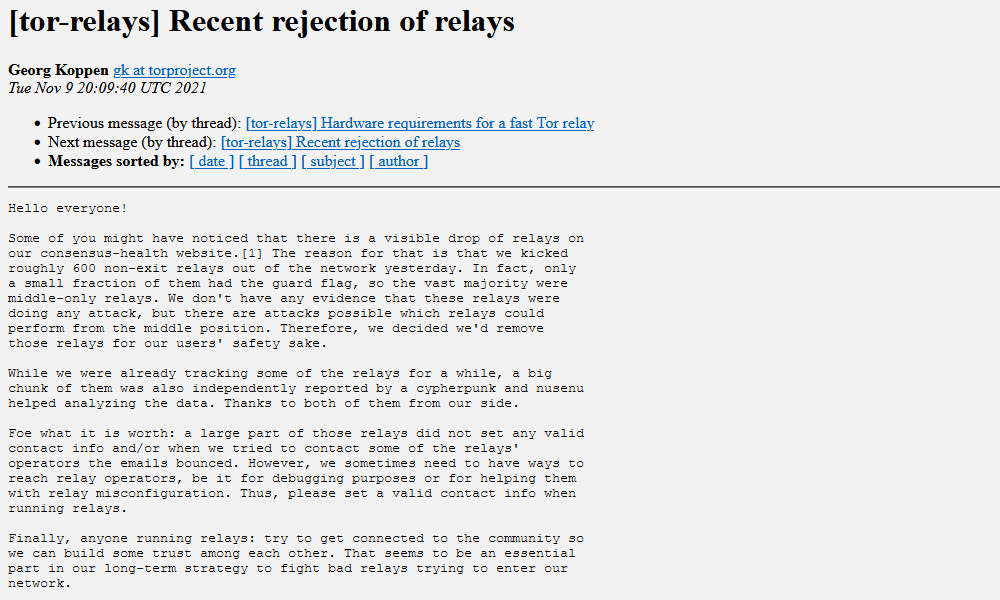

Servers added to the Tor network typically must have contact information included in their setup, such as an email address, so Tor network administrators and law enforcement can contact server operators in the case of a misconfiguration or file an abuse report.

However, despite this rule, servers with no contact information are often added to the Tor network, which is not strictly policed, mainly to ensure there's always a sufficiently large number of nodes to bounce and hide user traffic.

KAX17: Non-amateur level and persistent group

But a security researcher and Tor node operator going by Nusenu told The Record this week that it observed a pattern in some of these Tor relays with no contact information, which he first noticed in 2019 and has eventually traced back as far as 2017.

Grouping these servers under the KAX17 umbrella, Nusenu says this threat actor has constantly added servers with no contact details to the Tor network in industrial quantities, operating servers in the realm of hundreds at any given point.

The actor's servers are typically located in data centers spread all over the world and are typically configured as entry and middle points primarily, although KAX17 also operates a small number of exit points.

Nusenu said this is strange as most threat actors operating malicious Tor relays tend to focus on running exit points, which allows them to modify the user's traffic. For example, a threat actor that Nusenu has been tracking as BTCMITM20 ran thousands of malicious Tor exit nodes in order to replace Bitcoin wallet addresses inside web traffic and hijack user payments.

KAX17's focus on Tor entry and middle relays led Nusenu to believe that the group, which he described as "non-amateur level and persistent," is trying to collect information on users connecting to the Tor network and attempting to map their routes inside it.

In research published this week and shared with The Record, Nusenu said that at one point, there was a 16% chance that a Tor user would connect to the Tor network through one of KAX17's servers, a 35% chance they would pass through one of its middle relays, and up to 5% chance to exit through one.

"High probability of relays and guards can definitely be used to identify hidden services. It can also be used to decloak users -- especially if you have some other means to tracking middle relay past the guard, such as monitoring common public services," Dr. Neal Krawetz, an independent researcher studying the Tor network, told The Record in a conversation this week.

Nusenu told The Record he's been reporting KAX17's servers to the Tor Project since last year, with the Tor security team removing all of KAX17's exit relays in October 2020.

Another batch of Tor exit relays with no contact info came online immediately after the October 2020 removals, but Nusenu said he hasn't been able to link these new servers to KAX17 just yet, even if it is very likely that they are.

Hundreds of KAX17 Tor servers removed this year as well

Contacted for comment, a spokesperson for the Tor Project confirmed Nusenu's latest findings and said they also removed a batch of KAX17 malicious relays this year as well, in October, and a second batch in November.

"Once we got contacted, we looked through all the relays in the network and identified several hundred relays that are very likely belonging to the same group and removed them on November 8," a spokesperson told The Record.

This is not academic research

As for who is behind this group, neither Nusenu nor the Tor Project wanted to speculate.

"We are still investigating this attacker and can't provide links to any attribution so far," a Tor Project spokesperson told us in an email earlier yesterday.

However, Nusenu says that KAX17 made at least one operational security (OpSec) mistake in its early years when some of its servers did feature an email address.

Ironically, the threat actor reused the same email to sign up for the Tor Project mailing list and then participate in discussions and advocate against the removal of their malicious servers.

While all signs point to a nation-level and well-resourced threat actor who can afford to rent hundreds of high-bandwidth servers across the globe for no financial return, The Record did ask Nusenu about the possibility of KAX17 being an academic project studying Sybil attacks, a technique known to be able to deanonymize Tor traffic under certain conditions. The researcher replied that this was unlikely and provided the following arguments why (edited for grammar):

- Academic research is usually limited in time. KAX17 has been active since 2017.

- Researchers do not get involved in weakening anti-bad-relays policies on the Tor mailing list.

- Researchers do not fight against their removal and do not replace removed relays with new relays.

- Research-based relays usually run within 1-2 autonomous systems, not >50 ASes.

- Research relays usually run <100 relays, not >500.

- Research relays usually do have a relay ContactInfo.

- The Tor Project is quite well connected to the research community.

Catalin Cimpanu

is a cybersecurity reporter who previously worked at ZDNet and Bleeping Computer, where he became a well-known name in the industry for his constant scoops on new vulnerabilities, cyberattacks, and law enforcement actions against hackers.