GCHQ celebrates 80th anniversary of world's first digital computer, used to crack Nazi ciphers

GCHQ, the British signals and cyber intelligence agency, is celebrating the 80th anniversary of the Colossus computer by releasing a series of rare images and documents about the groundbreaking machine.

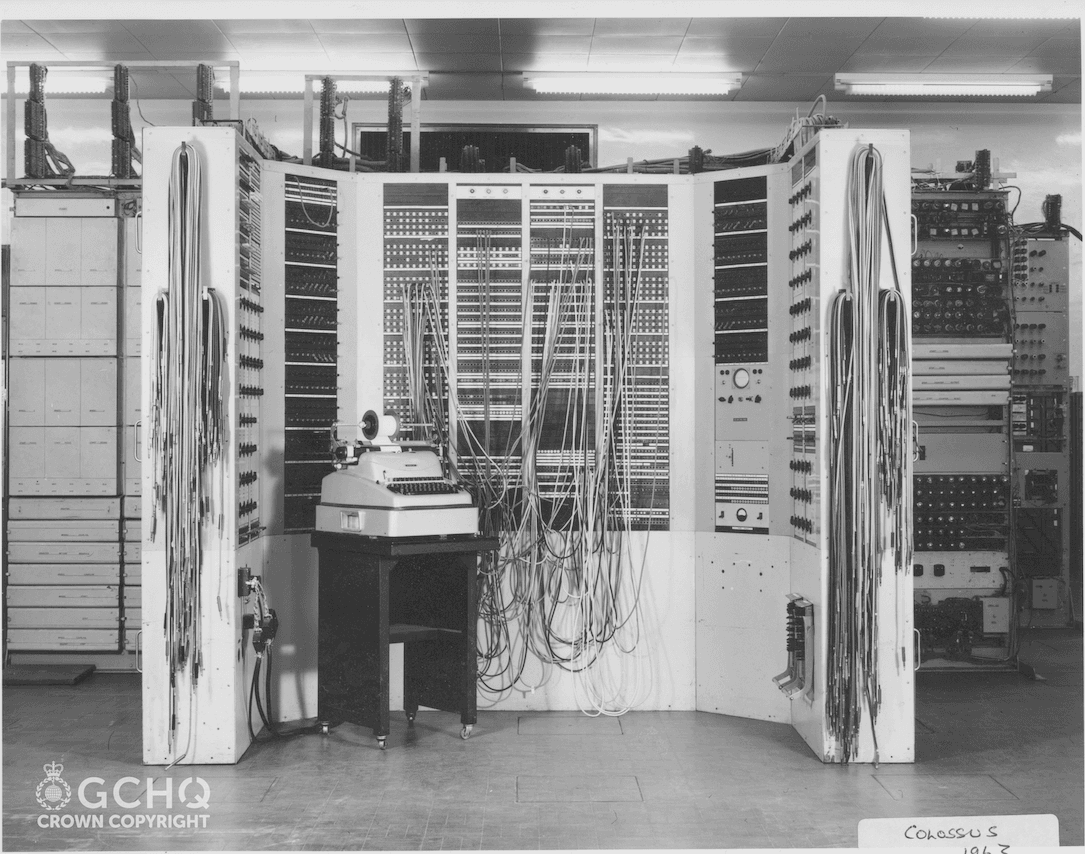

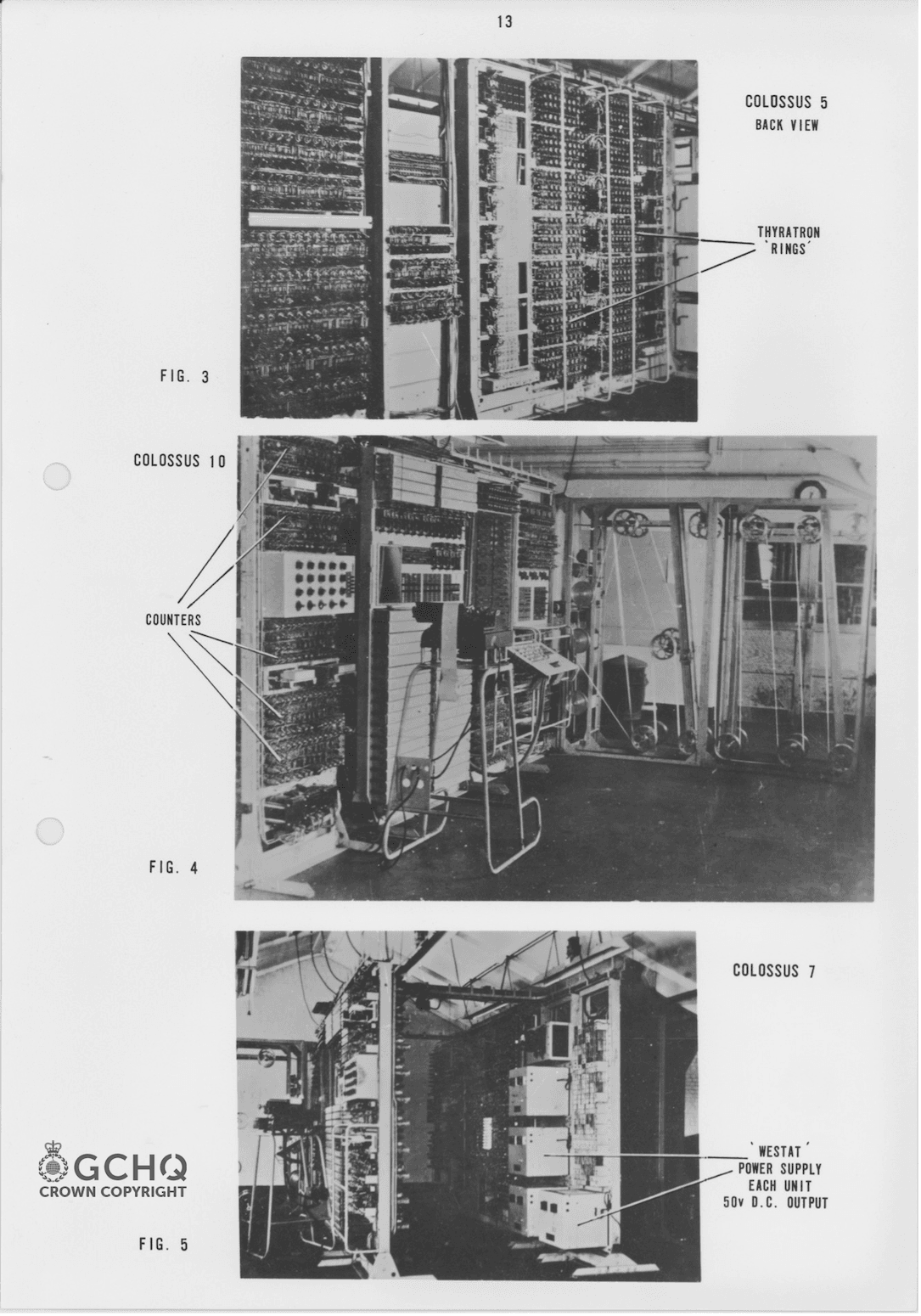

The release “sheds new light on the genesis and workings of Colossus, which was over two metres tall and considered by many to be the first ever digital computer,” according to GCHQ — although much of the material on the device in the National Archives remains classified.

Back on January 18 in 1944, a man called Tommy Flowers drove to Bletchley Park — the secret codebreaking facility about 50 miles north of London — in a truck carrying an enormous electronic machine that was instantly nicknamed Colossus.

Although we now know what Colossus was and what it was for — perhaps the first-ever digital computer, used to crack messages between senior German commanders encrypted with the Lorenz cipher — these details had remained secret until the year 2000.

Unlike its much more famous counterpart the Bombe, designed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman and used to crack the Enigma codes, almost everything about Colossus was kept under wraps for the best part of six decades — to the detriment of the recognition of those who had helped create it.

All images Crown Copyright – reproduced by kind permissions of Director GCHQ

All images Crown Copyright – reproduced by kind permissions of Director GCHQ

While modern computers work using electronic circuits that function as logic gates — these days using tiny semiconductors made from silicon — it was not possible to create logic gates in that way back in the 1940s.

Instead, Tommy Flowers created logic gates for Colossus from vacuum tubes — something only later adopted by ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer) which was, until the details about Colossus were made public, considered the world’s first digital computer.

The reasons for the secrecy are not known, although it has been speculated that Britain continued to export Lorenz cipher machines abroad up until the 1960s because Colossus meant it had the capability to decrypt Lorenz messages. The signals intelligence agency confirmed on Thursday that partly “because the technology was so effective, its functionality was still in use by GCHQ until the early 1960s.”

'No detailed user handbook'

In the press release accompanying the new documents, former GCHQ engineer Bill Marshall stated:

"I worked as an engineer on Colossus for a year during the 1960s. I had just signed the Official Secrets Act and knew nothing about GCHQ but was offered ‘interesting work’ which I believed would be dealing with telegrams for a government department.

I was told very little about the machine I was working on — what the machine was actually doing was not for me to know. My job was to repair it as necessary, using just a few circuit diagrams and no detailed user handbook. It wasn’t until much later that I found out that several of the systems and detailed design information were supposedly destroyed at the end of WWII.

I’m very proud to have been involved with Colossus even in just a small way, and we should all be proud of what was achieved in the name of national safety and security,” said Marshall.

After the war, eight of the ten Colossus machines were completely disassembled — although, of course, the engineers involved squirreled away the odd part and circuit diagram."

Based on these parts and diagrams, and a lot of interviews, the engineer Tony Sale led a rebuild of a working Colossus in the 1990s that was completed in 2007 and is currently housed at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

Andrew Herbert, the chairman of trustees at the museum, said: “Colossus was perhaps the most important of the wartime code breaking machines because it enabled the Allies to read strategic messages passing between the main German headquarters across Europe. This is one of the many reasons we’re so proud to have a fully working reconstruction of a Colossus code breaking machine on display at The National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

“From a technical perspective, Colossus was an important precursor of the modern electronic digital computer, and many of those who used Colossus at Bletchley Park went on to become important pioneers and leaders of British computing in the decades following the war, often leading the world in their work. We are proud to join with GCHQ in celebrating this significant date in the Colossus legacy,” added Herbert.

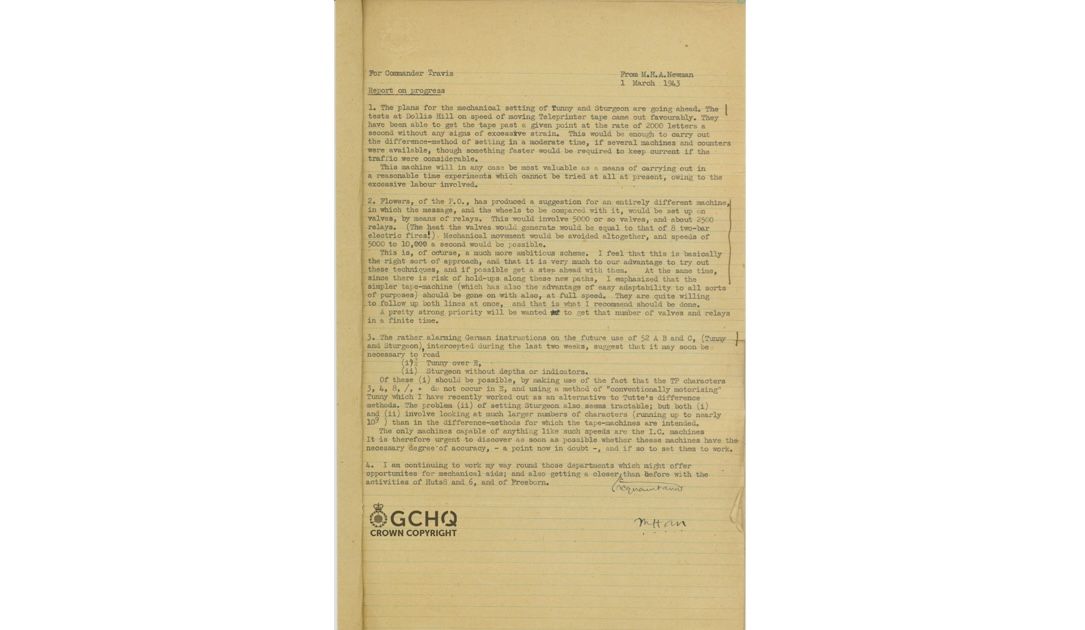

Progress report from Max Newman, 1943. (Click to enlarge)

Progress report from Max Newman, 1943. (Click to enlarge)

How important was it?

“The development of the Colossus machine was a huge advancement in Bletchley Park’s codebreaking efforts helping the Allies break one of the most complex ciphers of WWII,” said Ian Standen, the chief executive of Bletchley Park.

Objectively, there are challenges in directly measuring the value of intelligence gained by decrypting German military messages. However, indirectly there are some indications that the breaking of the Enigma code had a considerable impact on the Battle of the Atlantic.

This can be observed from the tonnage of shipping lost over a period in 1941 following the German Navy adding a fourth rotor to their Enigma machines — undermining Bletchley Park’s interception capabilities. During this period, losses in the Atlantic to U-boat attacks increased from 150,000 a month to 700,000 tonnes. Once the Allies had cracked the four-rotor Enigma, the losses returned to their previous levels.

An objective measure of the importance of Colossus, which was used to “decipher critical strategic messages between the most senior German Generals,” is harder to establish, although a letter released by GCHQ reveals that Colossus was intercepting what was considered “rather alarming German instructions.”

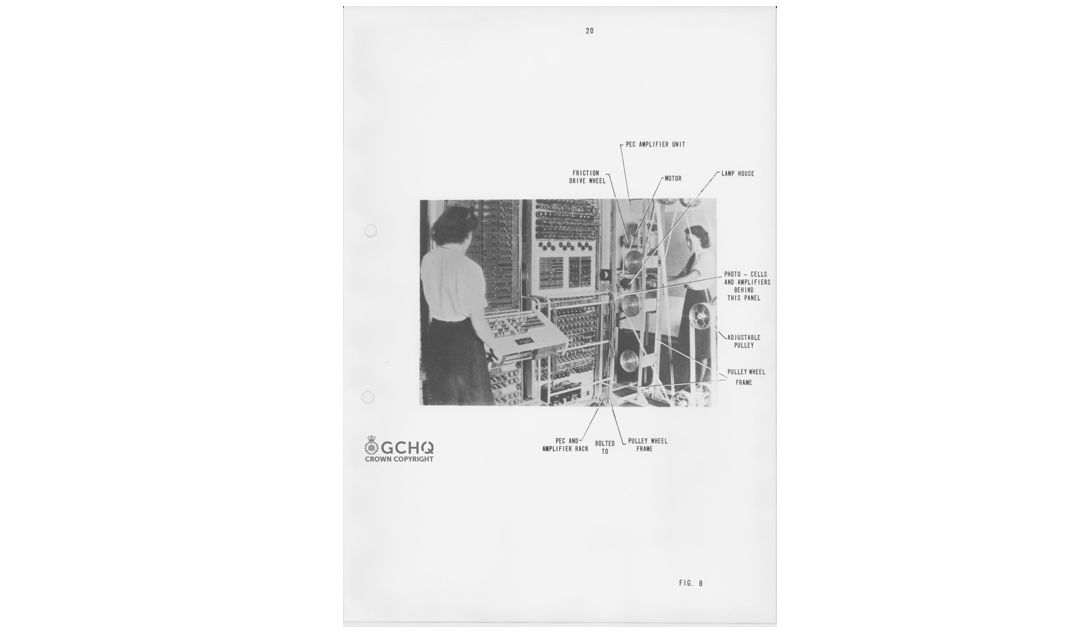

The tape reader assembly. (Click to enlarge)

The tape reader assembly. (Click to enlarge)

By the time the machine was delivered to Bletchley Park, planning for the D-Day landings was already underway, but it is argued that the intercepts Colossus provided were valuable for giving the go-ahead on June 6.

As explained by Chris Shore in his excellent lecture on the device for The Centre for Computing History:

"Being able to launch that invasion in early June was absolutely crucial, and they needed that up-to-date intelligence.

On June the fifth, Eisenhower met with his generals to decide whether to go on June the sixth. As they were meeting, so the story goes — and I believe this story is corroborated — a courier arrived from Bletchley Park, walked into the room, and handed Eisenhower a folded piece of paper.

Eisenhower opened that and read it, and what he read was a message that had been decrypted by Colossus at Bletchley Park just a few hours earlier, from Hitler in Berlin to Rommel, commander of the Nazi forces on the Atlantic wall.

And that message stated Hitler’s categorical belief that yes, there would be an invasion in Normandy, but that it would be a diversion, and that the real invasion would happen five days later in Calais. And that message specifically refused Rommel permission to move his tank divisions from Calais to Normandy to reinforce his defenses.

This was exactly the intelligence that Eisenhower had been waiting for - confirmation that the Nazi command had been completely deceived as to the timing and location of the attack.

Eisenhower didn’t reveal what he had just read — he wasn’t allowed to because people weren’t allowed to know that we were reading the German’s communications — he folded the paper up, he looked around at the assembled group of generals and he said simply, ‘Gentlemen, we go tomorrow.’”

Anne Keast-Butler, the director of GCHQ, said: “Technological innovation has always been at the center of our work here at GCHQ, and Colossus is a perfect example of how our staff keep us at the forefront of new technology – even when we can’t talk about it.

“The creativity, ingenuity and dedication shown by Tommy Flowers and his team to keep the country safe were as crucial to GCHQ then as today. I’m thrilled to be celebrating the 80th anniversary of this computer and honoring those who worked on it and then with it.”

Alexander Martin

is the UK Editor for Recorded Future News. He was previously a technology reporter for Sky News and a fellow at the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative, now Virtual Routes. He can be reached securely using Signal on: AlexanderMartin.79